Crime fiction/True Crime

Page 1 of 2

Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Crime fiction/True Crime

Crime fiction/True Crime

Mr Briggs' Hat: A Sensational Account of Britain's First Railway Murder by Kate Colquhoun – review

After a juddering start, Kate Colquhoun's account of the first murder on the British railway really gets going

Andrew Martin The Observer, Sunday 8 May 2011

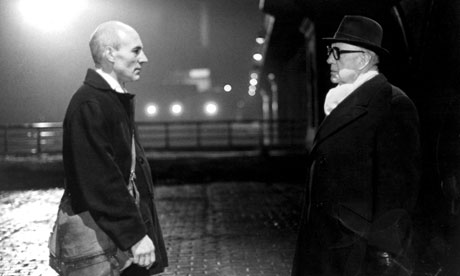

Franz Muller, a German tailor, was hanged in 1864 for the murder of Thomas Briggs. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Kate Summerscale scored a bestseller with her elegant account of a sensational mid-Victorian murder, The Suspicions of Mr Whicher. Now, here's an account of an almost equally sensational mid-Victorian murder, also with the word "Mr" in the title, also written by an author called Kate – circumstances tending to arouse in the present reviewer what might be called "The Suspicions of Mr Martin". Is this a proper book or a naked cash-in?

Mr Briggs' Hat: A Sensational Account of Britain's First Railway Murder by Kate Colquhoun

It's true that, unlike the country house murder investigated by Jack Whicher, the killing of 69-year-old Thomas Briggs in a first-class compartment of a North London Railway train on the evening of 9 July 1864 has not often been chronicled at length (even if it does rate a mention in most accounts of Victorian train travel). But at first I thought that Colquhoun was aiming at the bestseller lists with a piece of pure hackery. Early on, there's a pretty vacuous account of the rise of the railways. They spread news of national and international events to "the very edges of the country", would you believe? And in setting the scene of the killing, she writes: "Like most English locomotives at the time, each varnished teak carriage of the North London Railway train was divided into separate, isolated compartments," suggesting she has not absorbed the fairly elemental fact that the locomotive is the engine at the front of the train. (Later, Euston main line station is repeatedly referred to as "Euston Square", which is what the adjacent Underground station came to be called in 1909).

But as Mr Briggs makes his last peregrinations, I began to be drawn in. The particular, dreamy character of this murder is informed by the fact that it happened within the professional context of the City of London, yet on a summer Saturday. Mr Briggs – a senior bank clerk – worked on Saturdays, but only until 3pm. We meet him on Saturday morning, walking from Fenchurch Street station, terminus of the North London Railway, to his office in Lombard Street "under a warming sky filled with clouds smudged by greasy smog". After work, he takes a bus to Peckham in order to give a present to his niece. As he returns to the City in the evening, Colquhoun sketches in a low sun, and swallows wheeling in the sky. Besides writing with real forward momentum, she is good at atmosphere.

At Fenchurch Street, Briggs boarded the 9.45pm train that ought to have taken him to his home station: Hackney. But the train arrived at Hackney without Mr Briggs. Instead, there was a blood-soaked compartment containing what would prove to be Mr Briggs' bag, his stick and a crushed hat that had not belonged to him. The ladies in the next door compartment discovered that their dresses had been stained with drops of blood, which had apparently flown through the window of the one compartment into the next. But nobody had heard anything. Later on that balmy evening, Mr Briggs was found, battered and dying – and minus his gold watch and chain – by the side of the tracks leading to Hackney.

Suspicion soon alighted on a young, down-at-heel German-born tailor called Franz Muller, and Mr Briggs' Hat is a compelling read because innocent explanations are gradually posited for the following, apparently damning facts: that Muller was found in possession of Briggs's watch and possibly his hat; that the hat left in the carriage was also traced to him; that he sailed to America just days after the killing.

Muller was slightly built, and – on the face of it – remarkably inoffensive. Important evidence against him arose from the fact that he kindly gave a jewellers' branded cardboard box to the daughter of a friend to play with. The captain of the ship carrying him to America said that he was "one of the most agreeable passengers on board". When apprehended in New York by Detective Inspector Richard Tanner (who was from the same team of early detectives as Summerscale's Jack Whicher), he mildly inquired: "What is the matter?" On the journey back to Britain, he was very grateful when Tanner gave him The Pickwick Papers to read, and he chortled over the legal entanglements of the hero.

Even though the killing of Briggs was a "stranger murder", about which an urbanised society was becoming increasingly paranoid, it lacked the social and class resonance of Whicher's investigation. It did not, like that case, inspire some classic novels, but rather a sub-genre of crime stories concerning encounters with cads in railway compartments – a tide not stemmed by the introduction of communication cords. This was directly consequent upon the Muller case, as was the introduction, between compartments, of windows called Muller lights (which is now the name of a yoghurt, presumably so called by someone with little knowledge of railway history).

But this doesn't matter. The point is that the weight of evidence is in the balance to the very end. Was a just verdict achieved? The answer, mesmerisingly enough, seems to be "not quite".

Andrew Martin's latest novel is The Somme Stations (Faber)

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

After a juddering start, Kate Colquhoun's account of the first murder on the British railway really gets going

Andrew Martin The Observer, Sunday 8 May 2011

Franz Muller, a German tailor, was hanged in 1864 for the murder of Thomas Briggs. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Kate Summerscale scored a bestseller with her elegant account of a sensational mid-Victorian murder, The Suspicions of Mr Whicher. Now, here's an account of an almost equally sensational mid-Victorian murder, also with the word "Mr" in the title, also written by an author called Kate – circumstances tending to arouse in the present reviewer what might be called "The Suspicions of Mr Martin". Is this a proper book or a naked cash-in?

Mr Briggs' Hat: A Sensational Account of Britain's First Railway Murder by Kate Colquhoun

It's true that, unlike the country house murder investigated by Jack Whicher, the killing of 69-year-old Thomas Briggs in a first-class compartment of a North London Railway train on the evening of 9 July 1864 has not often been chronicled at length (even if it does rate a mention in most accounts of Victorian train travel). But at first I thought that Colquhoun was aiming at the bestseller lists with a piece of pure hackery. Early on, there's a pretty vacuous account of the rise of the railways. They spread news of national and international events to "the very edges of the country", would you believe? And in setting the scene of the killing, she writes: "Like most English locomotives at the time, each varnished teak carriage of the North London Railway train was divided into separate, isolated compartments," suggesting she has not absorbed the fairly elemental fact that the locomotive is the engine at the front of the train. (Later, Euston main line station is repeatedly referred to as "Euston Square", which is what the adjacent Underground station came to be called in 1909).

But as Mr Briggs makes his last peregrinations, I began to be drawn in. The particular, dreamy character of this murder is informed by the fact that it happened within the professional context of the City of London, yet on a summer Saturday. Mr Briggs – a senior bank clerk – worked on Saturdays, but only until 3pm. We meet him on Saturday morning, walking from Fenchurch Street station, terminus of the North London Railway, to his office in Lombard Street "under a warming sky filled with clouds smudged by greasy smog". After work, he takes a bus to Peckham in order to give a present to his niece. As he returns to the City in the evening, Colquhoun sketches in a low sun, and swallows wheeling in the sky. Besides writing with real forward momentum, she is good at atmosphere.

At Fenchurch Street, Briggs boarded the 9.45pm train that ought to have taken him to his home station: Hackney. But the train arrived at Hackney without Mr Briggs. Instead, there was a blood-soaked compartment containing what would prove to be Mr Briggs' bag, his stick and a crushed hat that had not belonged to him. The ladies in the next door compartment discovered that their dresses had been stained with drops of blood, which had apparently flown through the window of the one compartment into the next. But nobody had heard anything. Later on that balmy evening, Mr Briggs was found, battered and dying – and minus his gold watch and chain – by the side of the tracks leading to Hackney.

Suspicion soon alighted on a young, down-at-heel German-born tailor called Franz Muller, and Mr Briggs' Hat is a compelling read because innocent explanations are gradually posited for the following, apparently damning facts: that Muller was found in possession of Briggs's watch and possibly his hat; that the hat left in the carriage was also traced to him; that he sailed to America just days after the killing.

Muller was slightly built, and – on the face of it – remarkably inoffensive. Important evidence against him arose from the fact that he kindly gave a jewellers' branded cardboard box to the daughter of a friend to play with. The captain of the ship carrying him to America said that he was "one of the most agreeable passengers on board". When apprehended in New York by Detective Inspector Richard Tanner (who was from the same team of early detectives as Summerscale's Jack Whicher), he mildly inquired: "What is the matter?" On the journey back to Britain, he was very grateful when Tanner gave him The Pickwick Papers to read, and he chortled over the legal entanglements of the hero.

Even though the killing of Briggs was a "stranger murder", about which an urbanised society was becoming increasingly paranoid, it lacked the social and class resonance of Whicher's investigation. It did not, like that case, inspire some classic novels, but rather a sub-genre of crime stories concerning encounters with cads in railway compartments – a tide not stemmed by the introduction of communication cords. This was directly consequent upon the Muller case, as was the introduction, between compartments, of windows called Muller lights (which is now the name of a yoghurt, presumably so called by someone with little knowledge of railway history).

But this doesn't matter. The point is that the weight of evidence is in the balance to the very end. Was a just verdict achieved? The answer, mesmerisingly enough, seems to be "not quite".

Andrew Martin's latest novel is The Somme Stations (Faber)

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

Plugged by Eoin Colfer – review

Can a cult children's writer can cut it in crime?

Mark Lawson guardian.co.uk, Friday 20 May 2011 14.07 BST

Night work ... 'Colfer is an engaging and inventive writer with a strong sense of the rhythm of a story.' Photograph: Peter Dazeley/Getty Images

The rumour that JK Rowling may one day turn to crime has long persisted, despite any declaration of intent from her, because it clearly makes publishing sense to lure escapees from one of publishing's most lucrative genres – children's fiction – into another: mystery and suspense. Eoin Colfer, having achieved global eight-figure sales with the fantasy Artemis Fowl books and other juvenile ventures, is now attempting such a project with Plugged, his first adult crime novel. Colfer also wrote And Another Thing . . . , an impressive extension of the late Douglas Adams's Hitchhiker series, and so there's a sense of a successful author trying on new choices and voices, resisting the trap of being defined by a revered series.

Plugged by Eoin Colfer

In the journey towards crime fiction, Colfer is helped by the fact that his children's hero, Artemis Fowl, was a master criminal. The narrator of Plugged is also quite a dodgy dude. Daniel McEvoy is an ex-soldier, a common background for a character in this form, although his particular experience is promisingly fresh. Dan served with the Irish army, which has specialised in peacekeeping duties around the world – possibly because, as he points out before the reader can, of the excellent record of peaceful co-operation between communities on their own island. He served several tours in Lebanon and still carries shrapnel in his back from a Hezbollah rocket attack. However, now out of uniform and working as a doorman in New Jersey, his main medical concern is tonsorial. We meet Dan while he's waiting for the plugs to take from a recent hair transplant procedure.

This comedy of vanity in an action protagonist alerts us that we are in the territory of comedy crime, in the style of Carl Hiaasen or, on this side of the Atlantic, Christopher Brookmyre and Colin Bateman. Nicely summarising the house style, Dan at one point breaks off from describing a badinage-packed standoff with the baddies to observe: "I don't respond. All this wisecracking is more exhausting than the gunplay."

As shown by that quote, Plugged is told in sardonic monologue, a story-telling form that has the weakness of tipping off the reader that, even in the most tense scenes, the hero must survive; although as the dustjacket declares the novel to be the first of a series, his longevity is already taken as read. And the novel is not completely one-voiced: Dan is granted a kind of psychic sidekick. His best mate from the Lebanon, cosmetic surgeon Zeb Kronski, now missing, believed dead, keeps popping up as a taunting, prompting voice, speaking in italics.

By employing an Irish central character in an American setting, Colfer sensibly combines his own natural linguistic inheritance with a key publishing market. As Dan investigates the murder of an occasional New Jersey girlfriend, coming up against drug dealers and two female detectives with a complex sense of justice, there are numerous telling details, such as the small triangle in the corner of a car windscreen signalling that the glass is bulletproof – which, as our narrator notes, usefully narrows down the driver to "good guys, bad guys, or maybe a rapper praying someone will shoot him".

As he showed with the Artemis Fowl books, Colfer is an engaging and inventive writer with a strong sense of the rhythm of a story, its twists and riffs. His Douglas Adams continuation was also cleverly negotiated without damage to either the host franchise or his own reputation. But that Hitchhiker spin-off was inevitably, at some level, an exercise in superior pastiche; and a sense of prose karaoke also hangs over Plugged.

Always entertaining page by page, the book also has a truly unexpected sex scene and much sassy dialogue. However, there's a recurrent tic in which Dan worries that what's happening doesn't quite feel real to him. "It's what a Hollywood cop might say," he frets about one exchange with a detective. One comment meets the rejoinder that people say that kind of thing "only in movies". When someone kisses Dan, he frets that it's "like a movie kiss".

At the risk of sounding like Simon Moriarty, the Freudian army shrink who treats Dan's post-Lebanon stress disorder, these repeated references to the secondhand fictionality of the exercise might be taken as a psychological signal that Colfer fears a movie screen is intervening between him and his computer screen, that he is putting on borrowed clothes. In his experiments beyond the youth shelves, he is proving impressively versatile, but he needs to be wary of losing his own voice.

Mark Lawson's Enough is Enough is published by Picador.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Can a cult children's writer can cut it in crime?

Mark Lawson guardian.co.uk, Friday 20 May 2011 14.07 BST

Night work ... 'Colfer is an engaging and inventive writer with a strong sense of the rhythm of a story.' Photograph: Peter Dazeley/Getty Images

The rumour that JK Rowling may one day turn to crime has long persisted, despite any declaration of intent from her, because it clearly makes publishing sense to lure escapees from one of publishing's most lucrative genres – children's fiction – into another: mystery and suspense. Eoin Colfer, having achieved global eight-figure sales with the fantasy Artemis Fowl books and other juvenile ventures, is now attempting such a project with Plugged, his first adult crime novel. Colfer also wrote And Another Thing . . . , an impressive extension of the late Douglas Adams's Hitchhiker series, and so there's a sense of a successful author trying on new choices and voices, resisting the trap of being defined by a revered series.

Plugged by Eoin Colfer

In the journey towards crime fiction, Colfer is helped by the fact that his children's hero, Artemis Fowl, was a master criminal. The narrator of Plugged is also quite a dodgy dude. Daniel McEvoy is an ex-soldier, a common background for a character in this form, although his particular experience is promisingly fresh. Dan served with the Irish army, which has specialised in peacekeeping duties around the world – possibly because, as he points out before the reader can, of the excellent record of peaceful co-operation between communities on their own island. He served several tours in Lebanon and still carries shrapnel in his back from a Hezbollah rocket attack. However, now out of uniform and working as a doorman in New Jersey, his main medical concern is tonsorial. We meet Dan while he's waiting for the plugs to take from a recent hair transplant procedure.

This comedy of vanity in an action protagonist alerts us that we are in the territory of comedy crime, in the style of Carl Hiaasen or, on this side of the Atlantic, Christopher Brookmyre and Colin Bateman. Nicely summarising the house style, Dan at one point breaks off from describing a badinage-packed standoff with the baddies to observe: "I don't respond. All this wisecracking is more exhausting than the gunplay."

As shown by that quote, Plugged is told in sardonic monologue, a story-telling form that has the weakness of tipping off the reader that, even in the most tense scenes, the hero must survive; although as the dustjacket declares the novel to be the first of a series, his longevity is already taken as read. And the novel is not completely one-voiced: Dan is granted a kind of psychic sidekick. His best mate from the Lebanon, cosmetic surgeon Zeb Kronski, now missing, believed dead, keeps popping up as a taunting, prompting voice, speaking in italics.

By employing an Irish central character in an American setting, Colfer sensibly combines his own natural linguistic inheritance with a key publishing market. As Dan investigates the murder of an occasional New Jersey girlfriend, coming up against drug dealers and two female detectives with a complex sense of justice, there are numerous telling details, such as the small triangle in the corner of a car windscreen signalling that the glass is bulletproof – which, as our narrator notes, usefully narrows down the driver to "good guys, bad guys, or maybe a rapper praying someone will shoot him".

As he showed with the Artemis Fowl books, Colfer is an engaging and inventive writer with a strong sense of the rhythm of a story, its twists and riffs. His Douglas Adams continuation was also cleverly negotiated without damage to either the host franchise or his own reputation. But that Hitchhiker spin-off was inevitably, at some level, an exercise in superior pastiche; and a sense of prose karaoke also hangs over Plugged.

Always entertaining page by page, the book also has a truly unexpected sex scene and much sassy dialogue. However, there's a recurrent tic in which Dan worries that what's happening doesn't quite feel real to him. "It's what a Hollywood cop might say," he frets about one exchange with a detective. One comment meets the rejoinder that people say that kind of thing "only in movies". When someone kisses Dan, he frets that it's "like a movie kiss".

At the risk of sounding like Simon Moriarty, the Freudian army shrink who treats Dan's post-Lebanon stress disorder, these repeated references to the secondhand fictionality of the exercise might be taken as a psychological signal that Colfer fears a movie screen is intervening between him and his computer screen, that he is putting on borrowed clothes. In his experiments beyond the youth shelves, he is proving impressively versatile, but he needs to be wary of losing his own voice.

Mark Lawson's Enough is Enough is published by Picador.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

Survey anatomises British taste for murder

Research for Crime Writers' Association finds average crime novel's body count is 8.38

Alison Flood guardian.co.uk, Monday 13 June 2011 10.33 BST

Crime scene. Photograph: Alamy

Sliced to death in an olive machine? Decapitated by a glider cable? Squashed by a large brass wind instrument? These are just some of the ways in which victims were murdered over the last year by the UK's crime novelists.

A survey of the country's crime fiction authors by the Crime Writers' Association found that the average body count in crime novels over the last year was 8.38, with one particularly bloodthirsty writer killing off a whopping 150 victims. Means of killing varied from getting taxidermied alive to being poisoned with soluble aspirin and Ribena, given anaphylactic shock by bees in a wicket-keeper's inner glove, and getting trapped inside a Damien Hirst-style art installation.

The "Bloodthirsty Britain" survey was carried out to mark the start of National Crime Writing Week. Other inventive means of murder included rigging a euphonium to land on the victim's head, putting super glue in the victim's mouth and nostrils to suffocate them to death, and having the victim gored to death on the horns of a goat, said the CWA.

Despite the grisly ends met by so many of crime fiction's characters, one writer, asked why they enjoyed the genre, said that it can "illuminate and celebrate the human condition, not just tell grim stories". Another was considerably more bloodthirsty. Crime "creates suspense and allows you to explore the wicked/bad side of your own character that you don't actually want to act upon in real life. [It] allows you a window into that world without you having to participate," the writer said.

Bestselling crime novelist Peter James, chair of the CWA, said the survey's grisly findings "underline why readers so love crime writing".

"One of the big campaigns undertaken by the CWA at the moment is to support libraries and we know that crime forms the most popular genre when it comes to borrowings," said James. "This research emphasises the reason why it remains so popular."

Writers taking part in National Crime Writing Week include the award-winning Frances Fyfield and Ann Cleeves, former police officer and author of the Joe Hunter books Matt Hilton and the novelist SJ Bolton, whose thriller Blood Harvest was shortlisted for the Gold Dagger prize, with events taking place across the country.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Research for Crime Writers' Association finds average crime novel's body count is 8.38

Alison Flood guardian.co.uk, Monday 13 June 2011 10.33 BST

Crime scene. Photograph: Alamy

Sliced to death in an olive machine? Decapitated by a glider cable? Squashed by a large brass wind instrument? These are just some of the ways in which victims were murdered over the last year by the UK's crime novelists.

A survey of the country's crime fiction authors by the Crime Writers' Association found that the average body count in crime novels over the last year was 8.38, with one particularly bloodthirsty writer killing off a whopping 150 victims. Means of killing varied from getting taxidermied alive to being poisoned with soluble aspirin and Ribena, given anaphylactic shock by bees in a wicket-keeper's inner glove, and getting trapped inside a Damien Hirst-style art installation.

The "Bloodthirsty Britain" survey was carried out to mark the start of National Crime Writing Week. Other inventive means of murder included rigging a euphonium to land on the victim's head, putting super glue in the victim's mouth and nostrils to suffocate them to death, and having the victim gored to death on the horns of a goat, said the CWA.

Despite the grisly ends met by so many of crime fiction's characters, one writer, asked why they enjoyed the genre, said that it can "illuminate and celebrate the human condition, not just tell grim stories". Another was considerably more bloodthirsty. Crime "creates suspense and allows you to explore the wicked/bad side of your own character that you don't actually want to act upon in real life. [It] allows you a window into that world without you having to participate," the writer said.

Bestselling crime novelist Peter James, chair of the CWA, said the survey's grisly findings "underline why readers so love crime writing".

"One of the big campaigns undertaken by the CWA at the moment is to support libraries and we know that crime forms the most popular genre when it comes to borrowings," said James. "This research emphasises the reason why it remains so popular."

Writers taking part in National Crime Writing Week include the award-winning Frances Fyfield and Ann Cleeves, former police officer and author of the Joe Hunter books Matt Hilton and the novelist SJ Bolton, whose thriller Blood Harvest was shortlisted for the Gold Dagger prize, with events taking place across the country.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

This is the best True Crime book I've read in the last year or so, an account of an infamous 1860 Victorian country house murder case:

The official website tells you everything you need to know about book and author. Click here:

http://www.mrwhicher.com/

The official website tells you everything you need to know about book and author. Click here:

http://www.mrwhicher.com/

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

Criminal confessions

From safe crackers to cold-blooded hitmen, generations of outlaws have committed their high-octane lives to print. As one of Britain's best-known crime correspondents, Duncan Campbell spent his career in the company of such men. Here, he explores our appetite for their gory memoirs

Duncan Campbell The Observer, Sunday 3 July 2011

Gangster Billy Hill (on the right, with Hannen Swaffer – aka The Pope of Fleet Street – in the middle, and theatre impresario Henry Sherek) in 1955 Photograph: Bert Hardy/Getty Images

"My uncle Frank was a burglar and our family never saw any harm in that," runs the opening paragraph of Burglar to the Nobility, the autobiography of John "Ruby" Sparks. "But my mother did object to the way that he smooched around in baggy trousers, his jersey a different colour under the arms where sweat made it look as if a custard tart had melted there."

It is 50 years since the idiosyncratic confessions of one of the last century's most colourful villains was published, but the appetite for criminal memoirs remains as strong as ever. This month, some of the country's best-known former inmates will discuss how one of the simplest escape routes from prison and a life of crime is writing, at the Theakstons Old Peculier Crime Writing Festival in Harrogate. The law-abiding reader remains prepared to forgive almost anything in exchange for a glimpse of the wild side of life.

Few criminals today would manage to slip a melted custard tart and their uncle's sweaty armpits into their opening paragraph but Sparks was writing for a public that was still uncertain about its attitude to criminals chuckling over their misdeeds. "Ruby" Sparks had a number of claims to fame, including the nickname he acquired as a boy when he burgled a Mayfair mansion and stole £45,000- worth of a maharajah's rubies which he then gave away, mistaking them for cheap imitation jewels. In the 1920s he introduced motorised smash-and-grab to the streets of London with the assistance of getaway driver Lillian Goldstein, a middle-class young woman from Wembley; and he was a leader of the Dartmoor Mutiny, during which the inmates briefly took over the prison in 1932.

His book is a classic of the period, ghosted in larky, Runyonesque prose by Norman Price, with every robbery a "tickle" worth loads of "crinkle". Sparks ponders on why criminals spend the money they steal so swiftly: "It probably sounds a bit milky if I was to say now the reason which makes thieves and villains get through their ill-gotten wages so sharpish is they must inside themselves feel somehow guilty about it, but there's got to be some explanation why we all raced the gelt like we did." He concludes by explaining that he is now content to run a newsagent's in Chalk Farm and just wishes he had gone in for a "straight business" 40 years earlier.

Sadly, Goldstein never wrote her own memoirs, although Sparks credits her with some of the most inventive of his criminal techniques: she encouraged him to take bulldog paperclips with him on his smash-and-grabs to hold the cuts on his hands and arms together until she could stitch them up. She is quoted in the book as she bids a final farewell to Sparks, explaining her unwillingness to take part in a robbery with two young criminals which would involve throwing ammonia in someone's face: "I've had this Bandit Queen lark, crime is for kids – like those two greasy-haired spiv wonders – not for grown-ups."

Sparks was following in the footsteps of Eddie Guerin, whose Crime: The Autobiography of a Crook had been published in 1928. The London-born Guerin made his name as "king of the underworld" in Chicago and Paris, where he robbed the American Express office in 1901. His reputation was partly based on the belief that he had escaped from Devil's Island although it had, in fact, been another French penal colony. He clearly relished his early career – "what a red-hot game it was" – but acknowledged that "probably there will be readers who turn up their noses in disgust over a criminal setting down in cold print the unsavoury experiences of the past."

The book that set the postwar standard for the genre was Billy Hill's autobiography Boss of Britain's Underworld, ghosted by Duncan Webb, the enigmatic crime correspondent of the People. The launch party, in 1955, was held at Gennaro's – now the Groucho Club – and the Sunday Times reported it as an event that "made even Soho gasp… The guests included Sir Bernard and Lady Docker [celebrities before celebrities existed], former CID officers and many of London's scar-faced underworld."

From left: Soho Ted, Bugsy, Groin Frankie, Billy Hill, Ruby Sparks, Razor Frankie, College Harry, Frany the Spaniel, Cherry Bill, Johnny Ricco, a female journalist and Russian Ted enjoy the launch party for Billy Hill’s autobiography. Photograph: Bert Hardy/Getty Images

Guests were presented with a souvenir document bearing a red seal with Hill's autograph and fingerprints attached, and the proceedings opened with a blast from a police whistle. Hill's pals dressed up in masks and toy police helmets. Facetious congratulatory telegrams were read out. "Sorry I can't be here – I'm in a spot, Jack," said one – a crack at the expense of Hill's great underworld rival, Jack "Spot" Comer. "Will you send us back our mail – we miss it. Postmaster general," read another, a reference to Hill's role in the 1952 £287,000 robbery of a post office van for which no one was ever charged. Lady Docker and Hill posed for photographs together, while champagne and saddles of mutton were served.

The event was also covered by the Picture Post, with snaps by Bert Hardy, one of the great photographers of the era, and included shots of a chap known as "Striper". Not all of the media was impressed. The Daily Sketch's Simon Ward told his readers that there had been "nothing like it since the days of Al Capone in Chicago" and suggested that Hill had thrown "an astonishing party to cock a snook at the police".

Crime fiction writer Dreda Say Mitchell, author of Geezer Girls and Running Hot, and chair of this year's Harrogate festival, studied the criminal memoir long before she started her career. "I was a big reader of them even before I began writing as so many are based in the East End, where I grew up," she says. "Lennie 'The Guv' McLean's scrapyard was round the corner from our estate and The Blind Beggar (where Ronnie Kray shot George Cornell dead) was half a mile away. When it comes to writing crime though, [criminal memoirs] are not that helpful because they're nearly always co-written with professional journalists who know what publishers and readers want to hear – that the hero is a cross between Jesse James and Robin Hood – so the material is edited accordingly."

How such memoirs are regarded inside prison is another matter. "I had never read a criminal memoir before I went to prison," says Erwin James, who wrote a column about prison life for the Guardian during the final years of the 20 he served. "Books about crime and prison are among the most popular with prisoners. I think that's because, as a convicted criminal, in my case convicted of murder, you feel the weight of society's disgust and disapproval heavily and reading about how others in similar situations dealt with it can bring a lot of comfort."

Erwin James, writer and ex-prisoner. Photograph: David Levene

James, whose latest book, Life Before A Life Inside, is published next year, rates Papillon, by Henri Charrière, as the best of the genre. Others he values are Guerin's book, and Respect by Freddie Foreman, Autobiography of a Thief by Bruce Reynolds and Autobiography of a Murderer by Hugh Collins. He recalls reading Knightsbridge: Robbery of the Century, by Valerio Viccei, about the safety deposit heist which netted an estimated £40m in 1987. Viccei – "the Italian stallion" as the tabloids had him – was killed in 2000 in a shoot-out with police outside Rome when on day release from prison. No newsagent's in Chalk Farm for him.

"I was never usually drawn to books that affected to make criminal lifestyles appear glamorous," says James. "Meeting the often charismatic people you read about in the popular press – who operated as highly organised professional robbers, sometimes stealing tens of millions in cash, or gold – while they can indeed be attractive and compelling individuals and stand high in the prisoner hierarchy, the only real difference is that the photos they display on their cell walls are of luxury cars, big houses and expensive holiday locations. As the years pass in prison you see them getting old, missing families and harbouring huge regrets just like everyone else."

Former armed robber Noel "Razor" Smith, author of the much-admired A Few Kind Words and a Loaded Gun (2004) and A Rusty Gun (2010) was also initially wary of the criminal autobiography. "The reason I didn't want to write my own memoirs in the first place was because I had read so many of them and they were all the same. Reading their books you might be forgiven for believing that these geezers never lost a fight, always nicked over a million quid and never had a moment of fear or self-doubt. In the end I wanted to do something unique in the true-crime autobiography game: tell the actual truth! Sometimes I got my head kicked in and sometimes I went on a robbery and got nothing; that's what life as a criminal is really like."

Ex-con turned writer Noel “Razor” Smith in prison. Photograph: Sean Smith for the Guardian

In A Few Kind Words, Smith ruefully recalls his botched jobs, including one where he tried to hold up a newsagent's with a Luger pistol only to be told by its Ugandan-Asian proprietor, with commendable sang-froid, "Your gun is unloaded – you are minus the magazine. And you swear far too much for such a young man." An abashed Smith bought a Mars Bar instead. He reflects in A Rusty Gun: "When you're young and strong and you can afford to throw away a decade or two in some pisshole prison and still have plenty of life left to live, it's all a big laugh. Then you wake up one morning and see a strange face staring back at you from the shaving mirror. Some old geezer with bitter, weary eyes where there used to be a devil-may-care twinkle."

Cass Pennant was jailed for four years as a leader of the notorious West Ham football hooligans, the Inter City Firm (ICF). He emerged from prison not only to write a successful memoir, Cass, which was made into a film in 2008, but also to start a publishing house, Pennant Books, which has since brought out other tales of life on the wrong side of the law. He attributes the success of his book to the fact that it was truthful. "One thing I wanted to be sure of was that, if I had my own story published, it would be an honest one." McVicar by Himself, the autobiography of former robber John McVicar, is another volume that led to an eponymous film, starring Roger Daltrey.

Among the most original memoirs is Gentleman Thief (1995) by Peter Scott, who made and lost a fortune burgling the homes of the wealthy and notoriously stole Sophia Loren's diamonds. "Readers may relish the idea of a 'master criminal'; alas, such people don't exist," wrote Scott, now 80 and living on a rough estate in King's Cross, London. "Raffles was the stuff of fiction. Thieves in the main get caught. Persistent ones get caught more frequently, few escape the narrow aisles of pain." Freddie Foreman, author of Respect (1997), concludes by telling his fellow cons to "read everything and try to educate yourself towards a better life. The old ways have gone. Computers. Now that's the best advice I can give. There must be a clue there to have a good touch."

Reggie Kray with Barbara Windsor. Photograph: popperfoto

While the best book on the Kray twins remains a biography (John Pearson's Profession of Violence), the brothers' criminal careers helped to spawn more than a score of mainly unremarkable reminiscences by various henchmen. One familiar strand in such memoirs is to sound off about the sex offenders with whom the author has to share prison space. Thus Ronnie Knight (club owner, wide boy, former husband of Barbara Windsor) in Blood and Revenge: "What they need is branding on the forehead with a red-hot poker then decent rascals would know to blank them." So far, this is not among the government's beefed-up criminal justice proposals. Most memoirs are by former gangsters and robbers with only the occasional drugs smuggler (Howard Marks and his best seller Mr Nice) or informer (Maurice O'Mahoney and King Squealer) making an appearance.

The most successful are those that include self-reflection. Jimmy Boyle, former Glasgow hardman-turned-sculptor, wrote his autobiography, A Sense of Freedom, in 1977 in Barlinnie Prison. Boyle noted: "In writing the book in a manner that expresses all the hatred and rage that I felt at the time... I have been told that I lose the sympathy of the reader and that this isn't wise for someone who is still owned by the state and dependent on the authorities for a parole date... The book is a genuine attempt to warn young people that there is nothing glamorous about getting involved in crime and violence."

Two laws passed in the last decade could affect the business of true crime writing. The Criminal Justice Act of 2003 effectively brought an end to the concept of "double jeopardy". Previously, once a person had been acquitted of a crime they could not be retried for the same offence. This meant that a murderer could, if found not guilty, boast of it in a memoir without fear of the consequences. No more. Now an admission of a gangland hit could be all that the Director of Public Prosecutions requires to reopen a case.

No law prevents criminals from publishing their memoirs but there are restrictions on profiting from them, as enacted by the Coroners and Justice Act 2009. This enables courts to recover any assets that a criminal has acquired as a result of writing about their crimes. That money then goes into something called the Consolidated Fund. Those still serving a sentence can be prevented from publishing while in custody, as happened to serial killer Dennis Nilsen, whose autobiographical manuscript was confiscated. During the debate on the bill Baroness Rendell of Babergh (aka Ruth Rendell) pointed out that Jean Genet's The Thief's Journal might have fallen foul of such a law. In fact, great train robber Bruce Reynolds called his own memoir Autobiography of a Thief as a homage to Genet, whom he admired.

But neither of these laws, which have been only half-heartedly enforced since their enactment, seem likely to dent the public fascination with first-hand accounts of the criminal life. What George Orwell described in his essay, Decline of the English Murder, as the nation's "all-prevailing hypocrisy" should ensure that true crime will always find shelf space beside its fictional brothers and sisters. "When God erects a house of prayer, the devil always builds a chapel there," wrote Daniel Defoe, an ex-con who did a bit of writing himself. "And 'twill be found, upon examination, the latter has the larger congregation."

From safe crackers to cold-blooded hitmen, generations of outlaws have committed their high-octane lives to print. As one of Britain's best-known crime correspondents, Duncan Campbell spent his career in the company of such men. Here, he explores our appetite for their gory memoirs

Duncan Campbell The Observer, Sunday 3 July 2011

Gangster Billy Hill (on the right, with Hannen Swaffer – aka The Pope of Fleet Street – in the middle, and theatre impresario Henry Sherek) in 1955 Photograph: Bert Hardy/Getty Images

"My uncle Frank was a burglar and our family never saw any harm in that," runs the opening paragraph of Burglar to the Nobility, the autobiography of John "Ruby" Sparks. "But my mother did object to the way that he smooched around in baggy trousers, his jersey a different colour under the arms where sweat made it look as if a custard tart had melted there."

It is 50 years since the idiosyncratic confessions of one of the last century's most colourful villains was published, but the appetite for criminal memoirs remains as strong as ever. This month, some of the country's best-known former inmates will discuss how one of the simplest escape routes from prison and a life of crime is writing, at the Theakstons Old Peculier Crime Writing Festival in Harrogate. The law-abiding reader remains prepared to forgive almost anything in exchange for a glimpse of the wild side of life.

Few criminals today would manage to slip a melted custard tart and their uncle's sweaty armpits into their opening paragraph but Sparks was writing for a public that was still uncertain about its attitude to criminals chuckling over their misdeeds. "Ruby" Sparks had a number of claims to fame, including the nickname he acquired as a boy when he burgled a Mayfair mansion and stole £45,000- worth of a maharajah's rubies which he then gave away, mistaking them for cheap imitation jewels. In the 1920s he introduced motorised smash-and-grab to the streets of London with the assistance of getaway driver Lillian Goldstein, a middle-class young woman from Wembley; and he was a leader of the Dartmoor Mutiny, during which the inmates briefly took over the prison in 1932.

His book is a classic of the period, ghosted in larky, Runyonesque prose by Norman Price, with every robbery a "tickle" worth loads of "crinkle". Sparks ponders on why criminals spend the money they steal so swiftly: "It probably sounds a bit milky if I was to say now the reason which makes thieves and villains get through their ill-gotten wages so sharpish is they must inside themselves feel somehow guilty about it, but there's got to be some explanation why we all raced the gelt like we did." He concludes by explaining that he is now content to run a newsagent's in Chalk Farm and just wishes he had gone in for a "straight business" 40 years earlier.

Sadly, Goldstein never wrote her own memoirs, although Sparks credits her with some of the most inventive of his criminal techniques: she encouraged him to take bulldog paperclips with him on his smash-and-grabs to hold the cuts on his hands and arms together until she could stitch them up. She is quoted in the book as she bids a final farewell to Sparks, explaining her unwillingness to take part in a robbery with two young criminals which would involve throwing ammonia in someone's face: "I've had this Bandit Queen lark, crime is for kids – like those two greasy-haired spiv wonders – not for grown-ups."

Sparks was following in the footsteps of Eddie Guerin, whose Crime: The Autobiography of a Crook had been published in 1928. The London-born Guerin made his name as "king of the underworld" in Chicago and Paris, where he robbed the American Express office in 1901. His reputation was partly based on the belief that he had escaped from Devil's Island although it had, in fact, been another French penal colony. He clearly relished his early career – "what a red-hot game it was" – but acknowledged that "probably there will be readers who turn up their noses in disgust over a criminal setting down in cold print the unsavoury experiences of the past."

The book that set the postwar standard for the genre was Billy Hill's autobiography Boss of Britain's Underworld, ghosted by Duncan Webb, the enigmatic crime correspondent of the People. The launch party, in 1955, was held at Gennaro's – now the Groucho Club – and the Sunday Times reported it as an event that "made even Soho gasp… The guests included Sir Bernard and Lady Docker [celebrities before celebrities existed], former CID officers and many of London's scar-faced underworld."

From left: Soho Ted, Bugsy, Groin Frankie, Billy Hill, Ruby Sparks, Razor Frankie, College Harry, Frany the Spaniel, Cherry Bill, Johnny Ricco, a female journalist and Russian Ted enjoy the launch party for Billy Hill’s autobiography. Photograph: Bert Hardy/Getty Images

Guests were presented with a souvenir document bearing a red seal with Hill's autograph and fingerprints attached, and the proceedings opened with a blast from a police whistle. Hill's pals dressed up in masks and toy police helmets. Facetious congratulatory telegrams were read out. "Sorry I can't be here – I'm in a spot, Jack," said one – a crack at the expense of Hill's great underworld rival, Jack "Spot" Comer. "Will you send us back our mail – we miss it. Postmaster general," read another, a reference to Hill's role in the 1952 £287,000 robbery of a post office van for which no one was ever charged. Lady Docker and Hill posed for photographs together, while champagne and saddles of mutton were served.

The event was also covered by the Picture Post, with snaps by Bert Hardy, one of the great photographers of the era, and included shots of a chap known as "Striper". Not all of the media was impressed. The Daily Sketch's Simon Ward told his readers that there had been "nothing like it since the days of Al Capone in Chicago" and suggested that Hill had thrown "an astonishing party to cock a snook at the police".

Crime fiction writer Dreda Say Mitchell, author of Geezer Girls and Running Hot, and chair of this year's Harrogate festival, studied the criminal memoir long before she started her career. "I was a big reader of them even before I began writing as so many are based in the East End, where I grew up," she says. "Lennie 'The Guv' McLean's scrapyard was round the corner from our estate and The Blind Beggar (where Ronnie Kray shot George Cornell dead) was half a mile away. When it comes to writing crime though, [criminal memoirs] are not that helpful because they're nearly always co-written with professional journalists who know what publishers and readers want to hear – that the hero is a cross between Jesse James and Robin Hood – so the material is edited accordingly."

How such memoirs are regarded inside prison is another matter. "I had never read a criminal memoir before I went to prison," says Erwin James, who wrote a column about prison life for the Guardian during the final years of the 20 he served. "Books about crime and prison are among the most popular with prisoners. I think that's because, as a convicted criminal, in my case convicted of murder, you feel the weight of society's disgust and disapproval heavily and reading about how others in similar situations dealt with it can bring a lot of comfort."

Erwin James, writer and ex-prisoner. Photograph: David Levene

James, whose latest book, Life Before A Life Inside, is published next year, rates Papillon, by Henri Charrière, as the best of the genre. Others he values are Guerin's book, and Respect by Freddie Foreman, Autobiography of a Thief by Bruce Reynolds and Autobiography of a Murderer by Hugh Collins. He recalls reading Knightsbridge: Robbery of the Century, by Valerio Viccei, about the safety deposit heist which netted an estimated £40m in 1987. Viccei – "the Italian stallion" as the tabloids had him – was killed in 2000 in a shoot-out with police outside Rome when on day release from prison. No newsagent's in Chalk Farm for him.

"I was never usually drawn to books that affected to make criminal lifestyles appear glamorous," says James. "Meeting the often charismatic people you read about in the popular press – who operated as highly organised professional robbers, sometimes stealing tens of millions in cash, or gold – while they can indeed be attractive and compelling individuals and stand high in the prisoner hierarchy, the only real difference is that the photos they display on their cell walls are of luxury cars, big houses and expensive holiday locations. As the years pass in prison you see them getting old, missing families and harbouring huge regrets just like everyone else."

Former armed robber Noel "Razor" Smith, author of the much-admired A Few Kind Words and a Loaded Gun (2004) and A Rusty Gun (2010) was also initially wary of the criminal autobiography. "The reason I didn't want to write my own memoirs in the first place was because I had read so many of them and they were all the same. Reading their books you might be forgiven for believing that these geezers never lost a fight, always nicked over a million quid and never had a moment of fear or self-doubt. In the end I wanted to do something unique in the true-crime autobiography game: tell the actual truth! Sometimes I got my head kicked in and sometimes I went on a robbery and got nothing; that's what life as a criminal is really like."

Ex-con turned writer Noel “Razor” Smith in prison. Photograph: Sean Smith for the Guardian

In A Few Kind Words, Smith ruefully recalls his botched jobs, including one where he tried to hold up a newsagent's with a Luger pistol only to be told by its Ugandan-Asian proprietor, with commendable sang-froid, "Your gun is unloaded – you are minus the magazine. And you swear far too much for such a young man." An abashed Smith bought a Mars Bar instead. He reflects in A Rusty Gun: "When you're young and strong and you can afford to throw away a decade or two in some pisshole prison and still have plenty of life left to live, it's all a big laugh. Then you wake up one morning and see a strange face staring back at you from the shaving mirror. Some old geezer with bitter, weary eyes where there used to be a devil-may-care twinkle."

Cass Pennant was jailed for four years as a leader of the notorious West Ham football hooligans, the Inter City Firm (ICF). He emerged from prison not only to write a successful memoir, Cass, which was made into a film in 2008, but also to start a publishing house, Pennant Books, which has since brought out other tales of life on the wrong side of the law. He attributes the success of his book to the fact that it was truthful. "One thing I wanted to be sure of was that, if I had my own story published, it would be an honest one." McVicar by Himself, the autobiography of former robber John McVicar, is another volume that led to an eponymous film, starring Roger Daltrey.

Among the most original memoirs is Gentleman Thief (1995) by Peter Scott, who made and lost a fortune burgling the homes of the wealthy and notoriously stole Sophia Loren's diamonds. "Readers may relish the idea of a 'master criminal'; alas, such people don't exist," wrote Scott, now 80 and living on a rough estate in King's Cross, London. "Raffles was the stuff of fiction. Thieves in the main get caught. Persistent ones get caught more frequently, few escape the narrow aisles of pain." Freddie Foreman, author of Respect (1997), concludes by telling his fellow cons to "read everything and try to educate yourself towards a better life. The old ways have gone. Computers. Now that's the best advice I can give. There must be a clue there to have a good touch."

Reggie Kray with Barbara Windsor. Photograph: popperfoto

While the best book on the Kray twins remains a biography (John Pearson's Profession of Violence), the brothers' criminal careers helped to spawn more than a score of mainly unremarkable reminiscences by various henchmen. One familiar strand in such memoirs is to sound off about the sex offenders with whom the author has to share prison space. Thus Ronnie Knight (club owner, wide boy, former husband of Barbara Windsor) in Blood and Revenge: "What they need is branding on the forehead with a red-hot poker then decent rascals would know to blank them." So far, this is not among the government's beefed-up criminal justice proposals. Most memoirs are by former gangsters and robbers with only the occasional drugs smuggler (Howard Marks and his best seller Mr Nice) or informer (Maurice O'Mahoney and King Squealer) making an appearance.

The most successful are those that include self-reflection. Jimmy Boyle, former Glasgow hardman-turned-sculptor, wrote his autobiography, A Sense of Freedom, in 1977 in Barlinnie Prison. Boyle noted: "In writing the book in a manner that expresses all the hatred and rage that I felt at the time... I have been told that I lose the sympathy of the reader and that this isn't wise for someone who is still owned by the state and dependent on the authorities for a parole date... The book is a genuine attempt to warn young people that there is nothing glamorous about getting involved in crime and violence."

Two laws passed in the last decade could affect the business of true crime writing. The Criminal Justice Act of 2003 effectively brought an end to the concept of "double jeopardy". Previously, once a person had been acquitted of a crime they could not be retried for the same offence. This meant that a murderer could, if found not guilty, boast of it in a memoir without fear of the consequences. No more. Now an admission of a gangland hit could be all that the Director of Public Prosecutions requires to reopen a case.

No law prevents criminals from publishing their memoirs but there are restrictions on profiting from them, as enacted by the Coroners and Justice Act 2009. This enables courts to recover any assets that a criminal has acquired as a result of writing about their crimes. That money then goes into something called the Consolidated Fund. Those still serving a sentence can be prevented from publishing while in custody, as happened to serial killer Dennis Nilsen, whose autobiographical manuscript was confiscated. During the debate on the bill Baroness Rendell of Babergh (aka Ruth Rendell) pointed out that Jean Genet's The Thief's Journal might have fallen foul of such a law. In fact, great train robber Bruce Reynolds called his own memoir Autobiography of a Thief as a homage to Genet, whom he admired.

But neither of these laws, which have been only half-heartedly enforced since their enactment, seem likely to dent the public fascination with first-hand accounts of the criminal life. What George Orwell described in his essay, Decline of the English Murder, as the nation's "all-prevailing hypocrisy" should ensure that true crime will always find shelf space beside its fictional brothers and sisters. "When God erects a house of prayer, the devil always builds a chapel there," wrote Daniel Defoe, an ex-con who did a bit of writing himself. "And 'twill be found, upon examination, the latter has the larger congregation."

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

True Crime was one of the biggest selling sections in the bookshop I used to own , maybe it was just the area . I am not sure. Most of the buyers were women again I am not sure why . It was also the section from which most books were stolen !

Some crime fiction was very popular, however it was not as strong an area for sales as True Crime.

Some crime fiction was very popular, however it was not as strong an area for sales as True Crime.

Guest- Guest

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

PD James: a lifetime of crime

The writer talks about sexual violence in literature, the phone-hacking scandal – and why her new book might come as a surprise

Julie Bindel guardian.co.uk, Thursday 21 July 2011 18.30 BST

PD James: ‘We should have the freedom to make mistakes.’ Photograph: Geraint Lewis/Rex Features

PD James has been responsible for scores of rather nasty murders during the past five decades. But even one of the best imaginations in the whodunnit genre has to move with the times. While her most famous creation, policeman Adam Dalgliesh of New Scotland Yard, still has a huge and deeply loyal following, James has recently introduced gay characters into her novels; in another, an academic lost her job because the classics department made way for a media studies centre.

"What I do find difficult to understand is much of the behaviour and language of adolescents," she says. "I was researching what a 15-year-old would call the police. Is it Fizz or something? I can't keep up with it. In my day they were Bobbies."

James, AKA Phyllis Dorothy James, or Baroness James of Holland Park, OBE, is speaking to me from her home, just before she heads off to pick up a lifetime achievement award at a crime writing festival in Harrogate. "Being almost 91 makes receiving a lifetime achievement award all the more appropriate," James chuckles.

While Val McDermid and many contemporary female crime writers are increasingly developing plotlines involving serial killers and extremely violent sex crime, James can appear almost genteel and quaint in comparison. "My characters have sexual lives but there is no need for it to be so detailed. What I don't like is sexual gratuity. I don't want to write or read about lots of men writhing around."

Does James think female crime writers face particular barriers? She is reluctant to say, but reminds me of her female detective character Cordelia Gray, who has a more difficult time than her male contemporaries. "It is not a feminist plotline, but the reality is that a woman in her position would face difficulties that men would not. It is an inevitable part of her life."

For James, there are far more moral and ethical dilemmas to face today than when she was a young woman. She is concerned about the debate regarding assisted suicide and believes that it can be an encouragement to murder in some circumstances. "Death always advantages someone. I believe in the right of people who are living in torture to decide to end their lives but I am against any legal way to kill someone who wants to die. I would do it and face the consequences. I do not expect my country to change the law to suit my circumstances."

James took the Tory whip in the House of Lords, but insists she is not a "staunch Conservative". "I believe in the greatest possible freedom to the individual. I don't like this over-governing, and that is what we appear to have at present. We should have the freedom to make mistakes. My strongest belief is the importance of loving each other."

As she applies a stringent moral code in her novels, so she does in real life. We turn to the News International scandal. "Like all powerful people Murdoch has made enemies and there are many people who wish to keep the indignation going. But the Milly Dowler situation is appalling, and the person who gave the orders for her phone to be hacked can have no humanity at all. There is a dominant doctrine that says if you are the head of an organisation you fall on your sword when something goes wrong, and I think that is right. But it seems to no longer apply to bankers or politicians," she chuckles.

"And [former Met commissioner Sir Paul] Stephenson was guilty of what exactly?" she continues. "We've lost a good policeman."

Now, on days when she is working on a novel, James rises early and writes in longhand. Her secretary then types up her words, helps with emails and post, and organises James's diary. "I can barely do emails and am worse on my computer than a six-year-old," she says.

What is she currently writing? "A new novel, not Dalgliesh, which means that some people will be disappointed, but it is one I have been promising myself I would do for some time." Is it a departure from the Dalgliesh genre? Again she laughs. "Yes it is. I think you will be surprised.

"At my age the reality is that you just don't know what is around the corner. Once you are over 90 it is a bumpy ride."

The writer talks about sexual violence in literature, the phone-hacking scandal – and why her new book might come as a surprise

Julie Bindel guardian.co.uk, Thursday 21 July 2011 18.30 BST

PD James: ‘We should have the freedom to make mistakes.’ Photograph: Geraint Lewis/Rex Features

PD James has been responsible for scores of rather nasty murders during the past five decades. But even one of the best imaginations in the whodunnit genre has to move with the times. While her most famous creation, policeman Adam Dalgliesh of New Scotland Yard, still has a huge and deeply loyal following, James has recently introduced gay characters into her novels; in another, an academic lost her job because the classics department made way for a media studies centre.

"What I do find difficult to understand is much of the behaviour and language of adolescents," she says. "I was researching what a 15-year-old would call the police. Is it Fizz or something? I can't keep up with it. In my day they were Bobbies."

James, AKA Phyllis Dorothy James, or Baroness James of Holland Park, OBE, is speaking to me from her home, just before she heads off to pick up a lifetime achievement award at a crime writing festival in Harrogate. "Being almost 91 makes receiving a lifetime achievement award all the more appropriate," James chuckles.

While Val McDermid and many contemporary female crime writers are increasingly developing plotlines involving serial killers and extremely violent sex crime, James can appear almost genteel and quaint in comparison. "My characters have sexual lives but there is no need for it to be so detailed. What I don't like is sexual gratuity. I don't want to write or read about lots of men writhing around."

Does James think female crime writers face particular barriers? She is reluctant to say, but reminds me of her female detective character Cordelia Gray, who has a more difficult time than her male contemporaries. "It is not a feminist plotline, but the reality is that a woman in her position would face difficulties that men would not. It is an inevitable part of her life."

For James, there are far more moral and ethical dilemmas to face today than when she was a young woman. She is concerned about the debate regarding assisted suicide and believes that it can be an encouragement to murder in some circumstances. "Death always advantages someone. I believe in the right of people who are living in torture to decide to end their lives but I am against any legal way to kill someone who wants to die. I would do it and face the consequences. I do not expect my country to change the law to suit my circumstances."

James took the Tory whip in the House of Lords, but insists she is not a "staunch Conservative". "I believe in the greatest possible freedom to the individual. I don't like this over-governing, and that is what we appear to have at present. We should have the freedom to make mistakes. My strongest belief is the importance of loving each other."

As she applies a stringent moral code in her novels, so she does in real life. We turn to the News International scandal. "Like all powerful people Murdoch has made enemies and there are many people who wish to keep the indignation going. But the Milly Dowler situation is appalling, and the person who gave the orders for her phone to be hacked can have no humanity at all. There is a dominant doctrine that says if you are the head of an organisation you fall on your sword when something goes wrong, and I think that is right. But it seems to no longer apply to bankers or politicians," she chuckles.

"And [former Met commissioner Sir Paul] Stephenson was guilty of what exactly?" she continues. "We've lost a good policeman."

Now, on days when she is working on a novel, James rises early and writes in longhand. Her secretary then types up her words, helps with emails and post, and organises James's diary. "I can barely do emails and am worse on my computer than a six-year-old," she says.

What is she currently writing? "A new novel, not Dalgliesh, which means that some people will be disappointed, but it is one I have been promising myself I would do for some time." Is it a departure from the Dalgliesh genre? Again she laughs. "Yes it is. I think you will be surprised.

"At my age the reality is that you just don't know what is around the corner. Once you are over 90 it is a bumpy ride."

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

Re: Crime fiction/True Crime

Partners in crime fiction

Philip Marlowe, George Smiley, Nancy Drew, Count Fosco ... detectives, spies and villains are among our best-loved fictional characters. As the crime-writing world comes together for its annual festival, top authors in the genre choose their favourites. But who is your most wanted?

guardian.co.uk, Friday 22 July 2011 09.00 BST

Thriller instinct ... Patrick Stewart and Alec Guinness in the 1979 TV adaptation of John Le Carré's Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy. Photo: Everett Collection/Rex Features

Benjamin Black

The series of Parker books by Richard Stark – aka Donald Westlake – which began in the 1960s and ended with the author's sudden death on the last day of 2008 are among the finest crime novels of the past 50 years. Parker – we do not learn his first name, if indeed he has one – is an elemental force, a Nietzschean Übermensch beyond good and evil as well as the long arm of the law. He has no past outside the books, and no life except the one that his woman, Clare, makes for him. He is a sort of marvellous machine, and utterly convincing.

When we first encountered him, in The Hunter, published in 1962, he was a bit of a thug, "big and shaggy, with flat square shoulders and arms too long in sleeves too short", resembling the actor Jack Palance on whom Stark had modelled him. But as the series progressed he became leaner and smoother, a true professional, clinical, disinterested, ruthless, a man to see the job done and get away clean. The premise of nearly all the novels, however, is that something has gone wrong that Parker must fix, and will fix, no matter how many people have to be disposed of in the process. Not that Parker enjoys killing; in fact, he does his best to avoid it, since corpses make for a mess and clutter up the scene.

The books are all being republished by the admirable University of Chicago Press – it tickled Westlake that Parker should appear under an academic imprint – and among them are at least half a dozen masterpieces. They are intricately plotted, cool as burnished steel, exciting and intellectually satisfying.

Lee Child

My favourite crime series character? Instant temptation to name someone obscure, to prove I read more than you. Second temptation is to go full-on erudite, maybe asking whether someone from some 12th-century ballad isn't really the finest ever . . . as if to say, hey, I might make my living selling paperbacks out of the drugstore rack, but really I'm a very serious person.

Third temptation is to pick someone from way back who created or defined the genre. But the problem with characters from way back is that they're from, well, way back. Like the Model T Ford. It created and defined the automobile market. You want to drive one to work tomorrow? No, I thought not. You want something that built on its legacy and left it far behind.

Same for crime series characters. So, which one took crime fiction's long, grand legacy, and respected it, and yet still came out with something fresh and new and significant? Martin Beck is the one. He exists in 10 1960s and 70s novels by the Swedish Marxist team of Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö. They did two things with Beck: they created the normal-cop-in-a-normal-city paradigm, the dour guy a little down on his luck; and they used a crime series explicitly as social critique. All was not well in Sweden, they thought, and they said so through accessible entertainment rather than political screeds.

And along the way they gave birth to a whole stream of successors. From the current Scandinavians to Martin Cruz Smith's Arkady Renko to Ian Rankin's John Rebus, they're all Martin Beck's grandchildren.

Len Deighton

". . . a dirty rapscallion of a boy with a crooked tie and a grimy collar". So said the caption to one of Thomas Henry's wonderful drawings with which all the William books are illustrated. William Brown's simple and undaunted opposition to authority in all its many forms captivated me as soon as I started reading of his adventures. I was about eight years old.

Richmal Crompton (1890-1969), classics scholar and creator of William, regarded these stories as "potboilers". But from the time the first collection was published in 1922 she touched a nerve with many thousands of readers, both young and old. There are 38 William books in all, short stories rather than novels. Most writers do not fully understand the source of their creations, and it is Crompton's satire that makes so many readers laugh aloud at William's terrible truths. In the summer of 1923, Crompton – a kind and delightful lady by all accounts – was stricken by polio. Unmarried and with little money, she became dependent on her writing talents. Such was the success of William's anarchic philosophy that by 1927 she had a fine house built to her own design.

Lucky Jim, Harry Potter and Adrian Mole can all trace their family tree back to William and his long-suffering family. It is William's spirit of upbeat anarchy that distinguishes so many British crime stories from their tough-guy American counterparts. His pronouncements are social, political and philosophical but his adventures are catastrophic. William does not recognise catastrophe. Britain's wartime slogan "Keep calm and carry on" might have been his motto. Is William English, rather than British? I think so. Is he a male chauvinist pig? Undoubtedly. Did Richmal Crompton know what she was doing? Perhaps not: but what writer does?

RJ Ellory

The single-minded investigator; the man who possesses an almost inherent ability to comprehend the utterly irrational "rationale" of the serial killer, to live "inside his skin", to see the world through his eyes, and thus predict his intentions.

For me, this character is perhaps best personified by Thomas Harris's Will Graham. We meet him in Red Dragon in 1981. He's mentioned only in passing in The Silence of the Lambs and yet – such is the stature of this character – he has become a representation of the troubled, lone investigator.

Graham is a masterpiece of characterisation. First and foremost a homicide detective in New Orleans, he then studied forensic science at George Washington University. Assigned to a teaching post at the FBI Academy, he possesses a profound ability to empathise with the serial killers he pursues. He is haunted by this ability. He seeks to escape from his internal world, but cannot deny the obligation to identify those who perpetrate such heinous crimes. Graham is a legend, responsible for the killing of the serial killer known as the "Minnesota Shrike" and the capture of the "Chesapeake Ripper", aka Hannibal Lecter. He later consults with Lecter regarding an investigation into yet another killer, the "Tooth Fairy".

We see into Graham's inner world, and yet much of it remains obscured. We want him to look, to delve ever deeper into the darkness, but we know that with each further journey he takes into this underworld of the human psyche, he'll lose a little more of his humanity. We want him to succeed, but we appreciate the price he pays for that success. We admire his courage, his perseverance, his brilliance, but we are almost afraid of his darker self. We wonder, even, if he will ultimately become that which he so intensely loathes. As Nietzsche wrote: "He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster."

Frederick Forsyth

"Broke the mould" is an overused expression but sometimes it is absolutely fitting. One such occasion was the publication of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. Eight words is too long, but never mind. This book shattered all previous conceptions of espionage. It put an end to the image of Kiplingesque schoolboys playing the Great Game on the Northwest Frontier, to Richard Hannay's ineffable naivety against the German imperial war machine, the languid Ashendens exchanging pleasantries in scented salons, and to the great-fun-but-ridiculous James Bonds as convincing portrayals of anything resembling the real thing.

It revealed espionage as the devious, sly, unscrupulous practice of deception and mendacity – all for Queen and country. And it featured the master of them all, then and ever since: George Smiley. He was a fleeting figure in From the Cold but triumphed in the subsequent trilogy.

For those who read the books and saw the superb TV series, the mental image will always be that of the late, great Alec Guinness. He gave us the gentle ruthlessness, the onion-layered mind, the soft-spoken lethality of what we would like to think of as a senior British intelligence officer. The fact they are nothing like that is just bad luck. In daydreams Smiley will always remain the consummate spymaster.

Nicci French

The leading characters in Wilkie Collins's The Woman in White show that the greatest thrillers are written half with sharp, shining intelligence and half with murky, moonlit subconscious.

Close your eyes and what do you remember of the book? Shadows, ghosts, ruins and doppelgängers. A madwoman emerging from a Hampstead fog. The villain, Count Fosco, who keeps white mice in his pocket. Marian Halcombe, an intrepid heroine with, of all things, a light moustache – the reader sees her first from behind, dark-haired and shapely; then she turns and is revealed as ugly.

Marian Halcombe's ugliness makes her unmarriageable and unacceptable as a heroine of a Victorian novel. Fosco alone is captivated by her vitality and intelligence and judges her a worthy antagonist. Fosco himself is enormously fat, unfathomably clever, charismatic and gleefully villainous. He concocts a baroque crime, seemingly for his own enjoyment, and ours.

In the second half of the novel, Collins loses his nerve and subordinates and constrains Fosco and Marian in favour of the pallid official hero and heroine. Penniless, decent Walter Hartright and the pretty orphan-heiress Laura Fairlie are as bland as their names.

But Fosco remains the prototype of the gleeful villain, from Ernst Blofeld to Hannibal Lecter, while Marian Halcombe is a new kind of heroine – excluded, overlooked, even by Collins, yet one of the greatest female characters in Victorian literature. These two – the spooky, smiling gothic grotesque and the strong, unsung, unseen feminist – break though the book's official structure and remain in our imaginations long after the fevered story is done.

Tess Gerritsen

Ask any female American crime writer which fictional sleuth most influenced her early interest in the genre and chances are the answer will be: Nancy Drew, of course! Written by a number of authors under the pseudonym Carolyn Keene, the Nancy Drew novels featured a plucky 18-year-old amateur sleuth whose curiosity and single-minded pursuit of answers often lands her in tricky situations. As a child, I spent many a night huddled under the sheet with a flashlight, reading about Nancy's latest death-defying escape. Armed only with courage and cleverness (and sometimes with the help of her two loyal girlfriends), Nancy proved that girls, too, could track down bad guys. She inspired female crime writers as well as a whole generation of feminists who saw, thanks to Nancy, that the adventures we yearned for were within our reach.

Sophie Hannah