Children's fiction

4 posters

Page 1 of 2

Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Children's fiction

Children's fiction

The Alice Behind Wonderland by Simon Winchester – review

There are no simple conclusions about Lewis Carroll's photos of Alice

Stephen Bates The Guardian, Saturday 16 April 2011

The original Alice in Wonderland ... detail from Lewis Carroll's photograph (c 1862) of Alice Liddell, thought by Tennyson to be the most beautiful photograph he had ever seen. Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

If one thing that we know for sure about Lewis Carroll is that he was a shy Victorian bachelor Oxford maths don named Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, another thing we think we know is that he had sexual feelings towards children. All those photographs he took of pre-pubescent minors, some in the nude, some pouting provocatively – well, it stands to reason, as we impose modern speculation on the outlooks and sensibilities of a very different time.

The Alice Behind Wonderland by Simon Winchester

Acres of print have been expended on Carroll's surrealism and Dodgson's sexuality, and here now is a very brief monograph by the prolific Simon Winchester. It is scarcely more than a clearing of the throat or an extended article between his big books on earthquakes and the Atlantic, focusing forensically on one photograph and one relationship: that with Alice Pleasance Liddell, the original Alice.

The collodion picture, taken in the garden of the deanery at Christ Church, at that time occupied by Alice's father, on a summer's day in 1858, is perhaps the most notorious of the nine portraits Dodgson made of Alice alone over 13 years. It shows the six-year-old child, dressed as a beggar girl, leaning nonchalantly against a wall. Considering how new and complicated the photographic process was, the picture taken by the 26-year-old Dodgson is extraordinarily sharp and technically accomplished. It required patience and steadiness from the little girl, too: 45 seconds' worth as the lens cap was removed, then replaced. You can interpret her expression as either sultry or – perhaps more credibly – bored and somewhat impatient. The picture is unsettling, the artifice too obvious: her ragged clothes draped off the shoulder, her left nipple just exposed.

It would be another four years before Alice and her sisters, Dodgson and his friend Robinson Duckworth rowed up the Thames to Godstow on their famous picnic, listening to Dodgson's wonderland tale. Was this an extempore story, Duckworth asked. "Oh yes, I am just making it up as I go along," Dodgson replied. Three years later, the expanded story was published and has never since been out of print.

But it is the photograph that fascinates Winchester, and in dissecting it, and the story of how it came to be produced, he questions some of the myths. Dodgson's photographs of children would have been seen differently by the sentimental Victorians as portraits of innocence. Alice's siblings – also photographed that day – would have been present, as would, almost certainly, Alice's formidable mother Lorina, or at least her governess, Mary Prickett, any of whom could presumably have stopped anything inappropriate happening.

The evidence is that the Liddell children doted on Dodgson, though Mrs Liddell eventually tired of the frequency with which he brought his Thomas Ottewill Registered Double Folding camera to the deanery garden. When there was eventually a rupture in his friendship with the Liddells, it now seems not to have been about his friendship with the children but about his unsuitability as a suitor for their oldest daughter, Ina, four years older than Alice and approaching marriageable age. They thought the governess would be more appropriate for his station in life. Oxford dons at that time were expected to remain bachelors, and Dodgson did: no one would have thought that odd.

Alice Liddell lived into her 80s and died in 1934 – there is newsreel film of her on a 1932 visit to New York. She did not disavow her childhood friendship with the shy, stuttering don, though she did not remain in contact with him in adulthood. If there was unease about the relationship for other than snobbish reasons, she didn't mention it.

Winchester's book is clearly aimed at the US market, not only in spelling but in its quaint American formulations: Carroll apparently went to the Rugby school, and Christ Church seems to have had a "classics dean". All the sadder, then, that Princeton University, which holds the original Alice photograph, would not allow him even to see it.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

There are no simple conclusions about Lewis Carroll's photos of Alice

Stephen Bates The Guardian, Saturday 16 April 2011

The original Alice in Wonderland ... detail from Lewis Carroll's photograph (c 1862) of Alice Liddell, thought by Tennyson to be the most beautiful photograph he had ever seen. Photograph: Bettmann/Corbis

If one thing that we know for sure about Lewis Carroll is that he was a shy Victorian bachelor Oxford maths don named Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, another thing we think we know is that he had sexual feelings towards children. All those photographs he took of pre-pubescent minors, some in the nude, some pouting provocatively – well, it stands to reason, as we impose modern speculation on the outlooks and sensibilities of a very different time.

The Alice Behind Wonderland by Simon Winchester

Acres of print have been expended on Carroll's surrealism and Dodgson's sexuality, and here now is a very brief monograph by the prolific Simon Winchester. It is scarcely more than a clearing of the throat or an extended article between his big books on earthquakes and the Atlantic, focusing forensically on one photograph and one relationship: that with Alice Pleasance Liddell, the original Alice.

The collodion picture, taken in the garden of the deanery at Christ Church, at that time occupied by Alice's father, on a summer's day in 1858, is perhaps the most notorious of the nine portraits Dodgson made of Alice alone over 13 years. It shows the six-year-old child, dressed as a beggar girl, leaning nonchalantly against a wall. Considering how new and complicated the photographic process was, the picture taken by the 26-year-old Dodgson is extraordinarily sharp and technically accomplished. It required patience and steadiness from the little girl, too: 45 seconds' worth as the lens cap was removed, then replaced. You can interpret her expression as either sultry or – perhaps more credibly – bored and somewhat impatient. The picture is unsettling, the artifice too obvious: her ragged clothes draped off the shoulder, her left nipple just exposed.

It would be another four years before Alice and her sisters, Dodgson and his friend Robinson Duckworth rowed up the Thames to Godstow on their famous picnic, listening to Dodgson's wonderland tale. Was this an extempore story, Duckworth asked. "Oh yes, I am just making it up as I go along," Dodgson replied. Three years later, the expanded story was published and has never since been out of print.

But it is the photograph that fascinates Winchester, and in dissecting it, and the story of how it came to be produced, he questions some of the myths. Dodgson's photographs of children would have been seen differently by the sentimental Victorians as portraits of innocence. Alice's siblings – also photographed that day – would have been present, as would, almost certainly, Alice's formidable mother Lorina, or at least her governess, Mary Prickett, any of whom could presumably have stopped anything inappropriate happening.

The evidence is that the Liddell children doted on Dodgson, though Mrs Liddell eventually tired of the frequency with which he brought his Thomas Ottewill Registered Double Folding camera to the deanery garden. When there was eventually a rupture in his friendship with the Liddells, it now seems not to have been about his friendship with the children but about his unsuitability as a suitor for their oldest daughter, Ina, four years older than Alice and approaching marriageable age. They thought the governess would be more appropriate for his station in life. Oxford dons at that time were expected to remain bachelors, and Dodgson did: no one would have thought that odd.

Alice Liddell lived into her 80s and died in 1934 – there is newsreel film of her on a 1932 visit to New York. She did not disavow her childhood friendship with the shy, stuttering don, though she did not remain in contact with him in adulthood. If there was unease about the relationship for other than snobbish reasons, she didn't mention it.

Winchester's book is clearly aimed at the US market, not only in spelling but in its quaint American formulations: Carroll apparently went to the Rugby school, and Christ Church seems to have had a "classics dean". All the sadder, then, that Princeton University, which holds the original Alice photograph, would not allow him even to see it.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Last edited by eddie on Thu Apr 21, 2011 6:13 pm; edited 1 time in total

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Children's fiction

Re: Children's fiction

Here's what remains of the original ATU thread on Alice in Wonderland:

EXPIRED.

EXPIRED.

Last edited by eddie on Mon May 30, 2011 11:11 pm; edited 1 time in total

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Children's fiction

Re: Children's fiction

Enid Blyton legacy bequeathed to children's books centre

Newcastle-based Seven Stories will receive assets of Enid Blyton Trust for Children, which is being wound up

Alison Flood guardian.co.uk, Friday 17 June 2011 11.25 BST

Enid Blyton answering children's letters with a statue of Noddy to keep her company. Photograph: Popperfoto/Getty

A £750,000 legacy from the much-loved Famous Five author Enid Blyton is to go to the Newcastle-based children's books centre Seven Stories.

The fund comes from the Enid Blyton Trust for Children, which has worked for almost 30 years to support children in need. Its trustees, who include Blyton's daughter Imogen Smallwood, have now decided to retire, and are winding up the trust and donating its assets to Seven Stories.

"Our hope for Seven Stories is that the money from the Enid Blyton fund will continue to open up the world of books to as many children as possible," said the trustees in a statement. "The Enid Blyton Trust was founded in memory of all the charitable work Enid did during her life. When we decided to wind the Trust up our intention was to find an organisation for whom children and books are their raison d'etre."

The trustees said that Seven Stories was a "truy inspiring place", and that "Enid herself would feel very happy with everything Seven Stories is doing for her, her work and for the children". The centre is the only gallery dedicated to children's literature in the UK, and has been visited by 380,000 people since it opened in 1996. It houses one of the largest modern children's literature collections in Britain, with work from more than 80 authors and illustrators, including Philip Pullman, Edward Ardizzone, Judith Kerr and David Almond.

Last year, Seven Stories successfully bid at auction for a wealth of rare Blyton material, from a previously unpublished manuscript, Mr Tumpy's Caravan, to original typescripts of books from the Famous Five, Secret Seven, Malory Towers and Noddy series. Chief executive Kate Edwards said she was "thrilled" that the centre would be continuing the work of the Enid Blyton Trust "to improve the lives of children through learning and leisure opportunities".

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Newcastle-based Seven Stories will receive assets of Enid Blyton Trust for Children, which is being wound up

Alison Flood guardian.co.uk, Friday 17 June 2011 11.25 BST

Enid Blyton answering children's letters with a statue of Noddy to keep her company. Photograph: Popperfoto/Getty

A £750,000 legacy from the much-loved Famous Five author Enid Blyton is to go to the Newcastle-based children's books centre Seven Stories.

The fund comes from the Enid Blyton Trust for Children, which has worked for almost 30 years to support children in need. Its trustees, who include Blyton's daughter Imogen Smallwood, have now decided to retire, and are winding up the trust and donating its assets to Seven Stories.

"Our hope for Seven Stories is that the money from the Enid Blyton fund will continue to open up the world of books to as many children as possible," said the trustees in a statement. "The Enid Blyton Trust was founded in memory of all the charitable work Enid did during her life. When we decided to wind the Trust up our intention was to find an organisation for whom children and books are their raison d'etre."

The trustees said that Seven Stories was a "truy inspiring place", and that "Enid herself would feel very happy with everything Seven Stories is doing for her, her work and for the children". The centre is the only gallery dedicated to children's literature in the UK, and has been visited by 380,000 people since it opened in 1996. It houses one of the largest modern children's literature collections in Britain, with work from more than 80 authors and illustrators, including Philip Pullman, Edward Ardizzone, Judith Kerr and David Almond.

Last year, Seven Stories successfully bid at auction for a wealth of rare Blyton material, from a previously unpublished manuscript, Mr Tumpy's Caravan, to original typescripts of books from the Famous Five, Secret Seven, Malory Towers and Noddy series. Chief executive Kate Edwards said she was "thrilled" that the centre would be continuing the work of the Enid Blyton Trust "to improve the lives of children through learning and leisure opportunities".

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Last edited by eddie on Sat Jun 18, 2011 4:06 am; edited 2 times in total

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Children's fiction

Re: Children's fiction

From the old ATU site: "Welcome to Planet Narnia: CS Lewis' secret medieval structural code revealed":

Eddie wrote:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5aPQmoyzXx8

Planet Narnia trailer.

Eddie wrote:

From Times Online October 21, 2009

Welcome to the real Narnia

The hidden medieval message at the heart of C. S. Lewis's classic Chronicles

Tom Wright

Our age is dominated by Saturn, and it is time to rediscover Jupiter. It is safe to say that few if any of the millions who have read C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia would have summarized their message in those terms, taken from medieval planetary lore. Michael Ward, who with Planet Narnia has established himself not only as the foremost living Lewis scholar, but also as a brilliant writer in his own right, well knows that in advancing such an argument he risks being lumped with Dan Brown and other so-called discoverers of hidden codes. But his cumulative case for reading the Narnia books in terms of the planets (a brief preliminary account of which was given in the TLS of April 25, 2003) is overwhelming. These stories and their author deserve to be taken far more seriously in literary, cultural and philosophical terms than has hitherto been supposed.

Other controlling themes – the seven deadly sins, for instance – have been suggested for the seven Narnia stories (first published in the 1950s), but none has found much favour. Ward proposes, instead, that the books reflect and embody the thematic characteristics accorded in the medieval world-view to the seven planets, ie including the Sun and the Moon but excluding Uranus, Neptune and the now demoted Pluto. Thus The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe embodies Jupiter, Lewis’s favourite planet (a picture of which, accompanied by Earth, tiny on the same scale, adorns the book’s cover). This explains, and gives coherence to, the otherwise puzzling jumble of themes and characters (including Father Christmas) that Lewis’s friend J. R. R. Tolkien so disliked. Prince Caspian, with its military theme and imagery, embodies Mars. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, journeying towards an ever- larger Sun and discovering its aurifying influence, Ward regards as the “most obvious” novel to interpret under his scheme. Luna is seen to fine effect in The Silver Chair, and perhaps with more subtlety than Ward has yet explored; so too Mercury in The Horse and his Boy; Venus, initially surprisingly but with increasing conviction, in The Magician’s Nephew; and, climactically, Saturn, the planet of old age, despair and death, in The Last Battle. Here, however, there is a new turn. Once deception and decay have done their depressing work, Jupiter returns with the new creation of Narnia and its loyal inhabitants. The cosmos is after all a comedy, albeit dark and deep, not a tragedy.

If the books as a whole reflect the atmosphere or tone suggested by the different planets, their central character, the lion Aslan, takes on at least some of those same characteristics. Aslan is not simply a Christ-figure. Within and behind that obvious reference we are to discern the more subtle and varied tones of the planets – which themselves, as in the medieval writers who shaped Lewis’s world-view, are part of the good creation which is summed up, but not thereby diminished, in Christ. Here the interplay between Lewis’s professed Christianity and his mythic imagination is at its most profound.

To advance this remarkable thesis, Ward employs three interlocking strategies. The first, and most abstract, is to explore Lewis’s own theoretical musings about the “atmosphere” of a book or story. Lewis emphasized the difference between “contemplation” and “enjoyment”, between knowledge by observation and knowledge by acquaintance: between looking at a sunbeam and looking along it. The planetary mood or atmosphere of each book is not held up for “contemplation”, partly because Lewis himself, outwardly a what-you-see-is-what-you-get sort of person, actually believed in the equal importance of literary (and perhaps personal) concealment. Ward has discovered, in the one surviving typescript, a reference to Saturn which, in the published version, comes out as “old Father Time”. Lewis wanted to make people look along the planetary mood, not at it. That mood was to be “enjoyed”, tasted in the way a blindfolded person might taste seven dishes, savouring each without knowing their content or provenance. Ward is aware that by spilling the beans he may appear to jeopardize this strategy, but he argues convincingly that a more mature “enjoyment” is fully compatible with the new “contemplated” knowledge he expounds.

Lewis the critic referred to the “atmosphere” of a story as the “kappa element”, taking the term from the initial Greek letter of krypton (hidden). Ward, developing this, picks up a further coinage. Speaking of the “taste” or “atmosphere” of a particular place, Lewis says that we go back “to Donegal [a favourite of his] for its Donegality and London for its Londonness”. Ward boldly gives the word “donegality” a new metonymic meaning: not now the flavour of Donegal itself, but the idea of a particular flavour, atmosphere or mood, imparted to or expressed through a story. Lewis, he suggests, was attempting something quite new, calling for new terminology:

For the quality or atmosphere which arises out of a novel or a romance we may conveniently go on using such terms as “quality” and “atmosphere”, but for the deliberate encapsulation . . . of a pre-existing quality along with the presentation of an individual, Christological incarnation of that quality, it will be useful to have a new term.

Lewis was aiming at the literary equivalent of a musical effect. The obvious parallel with Holst’s Planets makes the point (Lewis admired the work, though he thought Holst’s “Jupiter” itself less than adequate, and his “Mars” too unremittingly evil). I do not know whether this kind of effect is actually unprecedented, but Ward has certainly detected and described it cogently. Whether the term “donegality” will catch on, or whether it will remain a quirky and somewhat awkward signpost to a previously unlabelled phenomenon, remains to be seen.

Ward’s second, more concrete, strategy is to lay bare the explicit role and meaning of the seven planets in Lewis’s other works. He has ransacked Lewis’s writings, not least his letters and the underlinings in his own copies of key poets, to show how well he knew the planets; he possessed his own telescope, was fond of pointing out particular planetary conjunctions to friends, and pondered long and deeply on their ancient meanings. Three writings in particular evince a universe of discourse within which the Narnia sequence fits like the wrought-iron key in a great medieval lock: “The Planets”, his alliterative poem of 1935, in relation to which Lewis said that “the characters of the planets” had “a permanent value as spiritual symbols”; the climax of That Hideous Strength, the finale of his science-fiction trilogy, in which the planetary spirits descend to Earth one by one, infusing the heroes of the story with their characteristic moods; and The Discarded Image, his full-on introduction to the medieval world-view. Ward expounds the narrative and meaning of each book to show, in outline and detail, how the story in general, and the characterization of Aslan in particular, fits with the atmosphere of the relevant planet as Lewis has elsewhere expounded it.

The match is not uniform, nor the world-view utterly consistent. How can there apparently be evil beyond the Moon’s orbit? (For the medievals, evil was only “beneath the moon”.) Why, in The Magician’s Nephew, reflecting Venus, is Aslan not female? Lewis has difficulty with the martial theme in Prince Caspian; he overdoes the word “pale” in The Silver Chair. But these are problems of detail, which Ward discusses with shrewd sensitivity, not threats to the theory.

Lewis himself warned against using authorial biography as a clue to critical analysis, but Ward’s third strategy, advanced cautiously but tellingly, is to read the Narniad and its planetary meanings within the setting of Lewis’s own life and lifelong concerns. He shows, against some of the biographers, that Lewis’s turn to children’s fiction was not so much an escape from the wounding public argument he had with the philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe about the nature of miracles, but, rather, a deliberate re-examination of the same topic by a more thoroughgoing way. Reason and Imagination, Athene and Demeter, must now work together: “maid and mother must be thus combined before one can conceive the universe aright, let alone envisage the God who made it”.

Overall, Ward locates Lewis’s underlying aim in the books as an expression of his oft- repeated opinion: Britain in the twentieth century was gripped by a Saturn-like mood, and needed to be reawakened to Jupiter. This explains Lewis’s strong reaction not only against his earlier favourite, Donne, but also against T. S. Eliot. Sadly, little is said (by Ward, certainly; by Lewis himself, so far as I know) about Lewis’s reading of Four Quartets, where Eliot might be supposed to be making a slow but powerful turn in the same direction, and where the theme of linguistic chaos redeemed at last echoes the closing stages of That Hideous Strength. And Ward demonstrates that Lewis, sometimes supposed to have been almost dualistic in his supernaturalism, was, in fact, not least as a reader of Hooker, a believer in the hierarchically layered unity of all created things and of their significance within the saving self-revelation of the Creator. Though intellectually a trinitarian Christian, imaginatively Lewis lived in the world of ancient paganism, finding in the medievals, particularly his beloved Dante, a way to reconcile the two, and in the Narniad a way to express that reconciled complexity. Lewis himself declared that “In Spenser, as in Milton and many others, Jove is often Jehovah incognito”. Yes, comments Ward, and “in The Lion, the divine figure [Aslan, playing the part of Christ] is Jove incognito”. Those who think they have discerned, and perhaps debunked, the Christian allegory in the Narniad have only traced the outskirts of Lewis’s ways. Perhaps Aslan’s, too.

This introduction to a masterpiece is something of a masterpiece in its own right. Lewis’s ghost (whom Lewis envisaged as a possible benign presence around Magdalene College, Cambridge) has reason to be grateful that the crucial discovery was made by someone capable of expounding it with such subtlety and depth. There are tiny blemishes, of which the reversal of the kappa and chi in the Greek word for character is perhaps the most obvious, but the overall effect is remarkable. Michael Ward has written a book whose “donegality” is the medieval scholarship, the poetic craftsmanship, the philosophical acumen and the imaginative genius of the self-consciously Jovial Lewis himself. It would be a great pity if the still prevailing Saturnine mood of our times, which has belittled and sometimes even reviled Lewis as a thinker, were to blind us to his remarkable literary, philosophical, cosmological and theological achievement.

Michael Ward

PLANET NARNIA

The seven heavens in the imagination of C. S. Lewis

347pp. Oxford University Press. Ł16.99 (US $29.95).

978 0 19 531387 1

Tom Wright is Bishop of Durham. His latest book is Justification: God’s plan and Paul’s vision, 2009. He is working on Volume Four of his series Christian Origins and the Question of God.

Eddie wrote:

Link to Michael Ward's Planet Narnia website:

http://www.planetnarnia.com/

Eddie wrote:

Loved Pauline Baynes' original Narnia illustrations:

Lucy and Mr Tumnus the faun.

Hosni wrote:

Oh, wot whimsy.

Dodgson: sexual predator

Barrie: defiler of the innocent

Lewis: flasher, general sex offender

John McLaughlin wrote:

didn't know that the medievals were ancient, and pagans to boot. THe things you pick up in lit crit.

Eddie wrote:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5aPQmoyzXx8

Planet Narnia trailer.

Eddie wrote:

From Times Online October 21, 2009

Welcome to the real Narnia

The hidden medieval message at the heart of C. S. Lewis's classic Chronicles

Tom Wright

Our age is dominated by Saturn, and it is time to rediscover Jupiter. It is safe to say that few if any of the millions who have read C. S. Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia would have summarized their message in those terms, taken from medieval planetary lore. Michael Ward, who with Planet Narnia has established himself not only as the foremost living Lewis scholar, but also as a brilliant writer in his own right, well knows that in advancing such an argument he risks being lumped with Dan Brown and other so-called discoverers of hidden codes. But his cumulative case for reading the Narnia books in terms of the planets (a brief preliminary account of which was given in the TLS of April 25, 2003) is overwhelming. These stories and their author deserve to be taken far more seriously in literary, cultural and philosophical terms than has hitherto been supposed.

Other controlling themes – the seven deadly sins, for instance – have been suggested for the seven Narnia stories (first published in the 1950s), but none has found much favour. Ward proposes, instead, that the books reflect and embody the thematic characteristics accorded in the medieval world-view to the seven planets, ie including the Sun and the Moon but excluding Uranus, Neptune and the now demoted Pluto. Thus The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe embodies Jupiter, Lewis’s favourite planet (a picture of which, accompanied by Earth, tiny on the same scale, adorns the book’s cover). This explains, and gives coherence to, the otherwise puzzling jumble of themes and characters (including Father Christmas) that Lewis’s friend J. R. R. Tolkien so disliked. Prince Caspian, with its military theme and imagery, embodies Mars. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, journeying towards an ever- larger Sun and discovering its aurifying influence, Ward regards as the “most obvious” novel to interpret under his scheme. Luna is seen to fine effect in The Silver Chair, and perhaps with more subtlety than Ward has yet explored; so too Mercury in The Horse and his Boy; Venus, initially surprisingly but with increasing conviction, in The Magician’s Nephew; and, climactically, Saturn, the planet of old age, despair and death, in The Last Battle. Here, however, there is a new turn. Once deception and decay have done their depressing work, Jupiter returns with the new creation of Narnia and its loyal inhabitants. The cosmos is after all a comedy, albeit dark and deep, not a tragedy.

If the books as a whole reflect the atmosphere or tone suggested by the different planets, their central character, the lion Aslan, takes on at least some of those same characteristics. Aslan is not simply a Christ-figure. Within and behind that obvious reference we are to discern the more subtle and varied tones of the planets – which themselves, as in the medieval writers who shaped Lewis’s world-view, are part of the good creation which is summed up, but not thereby diminished, in Christ. Here the interplay between Lewis’s professed Christianity and his mythic imagination is at its most profound.

To advance this remarkable thesis, Ward employs three interlocking strategies. The first, and most abstract, is to explore Lewis’s own theoretical musings about the “atmosphere” of a book or story. Lewis emphasized the difference between “contemplation” and “enjoyment”, between knowledge by observation and knowledge by acquaintance: between looking at a sunbeam and looking along it. The planetary mood or atmosphere of each book is not held up for “contemplation”, partly because Lewis himself, outwardly a what-you-see-is-what-you-get sort of person, actually believed in the equal importance of literary (and perhaps personal) concealment. Ward has discovered, in the one surviving typescript, a reference to Saturn which, in the published version, comes out as “old Father Time”. Lewis wanted to make people look along the planetary mood, not at it. That mood was to be “enjoyed”, tasted in the way a blindfolded person might taste seven dishes, savouring each without knowing their content or provenance. Ward is aware that by spilling the beans he may appear to jeopardize this strategy, but he argues convincingly that a more mature “enjoyment” is fully compatible with the new “contemplated” knowledge he expounds.

Lewis the critic referred to the “atmosphere” of a story as the “kappa element”, taking the term from the initial Greek letter of krypton (hidden). Ward, developing this, picks up a further coinage. Speaking of the “taste” or “atmosphere” of a particular place, Lewis says that we go back “to Donegal [a favourite of his] for its Donegality and London for its Londonness”. Ward boldly gives the word “donegality” a new metonymic meaning: not now the flavour of Donegal itself, but the idea of a particular flavour, atmosphere or mood, imparted to or expressed through a story. Lewis, he suggests, was attempting something quite new, calling for new terminology:

For the quality or atmosphere which arises out of a novel or a romance we may conveniently go on using such terms as “quality” and “atmosphere”, but for the deliberate encapsulation . . . of a pre-existing quality along with the presentation of an individual, Christological incarnation of that quality, it will be useful to have a new term.

Lewis was aiming at the literary equivalent of a musical effect. The obvious parallel with Holst’s Planets makes the point (Lewis admired the work, though he thought Holst’s “Jupiter” itself less than adequate, and his “Mars” too unremittingly evil). I do not know whether this kind of effect is actually unprecedented, but Ward has certainly detected and described it cogently. Whether the term “donegality” will catch on, or whether it will remain a quirky and somewhat awkward signpost to a previously unlabelled phenomenon, remains to be seen.

Ward’s second, more concrete, strategy is to lay bare the explicit role and meaning of the seven planets in Lewis’s other works. He has ransacked Lewis’s writings, not least his letters and the underlinings in his own copies of key poets, to show how well he knew the planets; he possessed his own telescope, was fond of pointing out particular planetary conjunctions to friends, and pondered long and deeply on their ancient meanings. Three writings in particular evince a universe of discourse within which the Narnia sequence fits like the wrought-iron key in a great medieval lock: “The Planets”, his alliterative poem of 1935, in relation to which Lewis said that “the characters of the planets” had “a permanent value as spiritual symbols”; the climax of That Hideous Strength, the finale of his science-fiction trilogy, in which the planetary spirits descend to Earth one by one, infusing the heroes of the story with their characteristic moods; and The Discarded Image, his full-on introduction to the medieval world-view. Ward expounds the narrative and meaning of each book to show, in outline and detail, how the story in general, and the characterization of Aslan in particular, fits with the atmosphere of the relevant planet as Lewis has elsewhere expounded it.

The match is not uniform, nor the world-view utterly consistent. How can there apparently be evil beyond the Moon’s orbit? (For the medievals, evil was only “beneath the moon”.) Why, in The Magician’s Nephew, reflecting Venus, is Aslan not female? Lewis has difficulty with the martial theme in Prince Caspian; he overdoes the word “pale” in The Silver Chair. But these are problems of detail, which Ward discusses with shrewd sensitivity, not threats to the theory.

Lewis himself warned against using authorial biography as a clue to critical analysis, but Ward’s third strategy, advanced cautiously but tellingly, is to read the Narniad and its planetary meanings within the setting of Lewis’s own life and lifelong concerns. He shows, against some of the biographers, that Lewis’s turn to children’s fiction was not so much an escape from the wounding public argument he had with the philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe about the nature of miracles, but, rather, a deliberate re-examination of the same topic by a more thoroughgoing way. Reason and Imagination, Athene and Demeter, must now work together: “maid and mother must be thus combined before one can conceive the universe aright, let alone envisage the God who made it”.

Overall, Ward locates Lewis’s underlying aim in the books as an expression of his oft- repeated opinion: Britain in the twentieth century was gripped by a Saturn-like mood, and needed to be reawakened to Jupiter. This explains Lewis’s strong reaction not only against his earlier favourite, Donne, but also against T. S. Eliot. Sadly, little is said (by Ward, certainly; by Lewis himself, so far as I know) about Lewis’s reading of Four Quartets, where Eliot might be supposed to be making a slow but powerful turn in the same direction, and where the theme of linguistic chaos redeemed at last echoes the closing stages of That Hideous Strength. And Ward demonstrates that Lewis, sometimes supposed to have been almost dualistic in his supernaturalism, was, in fact, not least as a reader of Hooker, a believer in the hierarchically layered unity of all created things and of their significance within the saving self-revelation of the Creator. Though intellectually a trinitarian Christian, imaginatively Lewis lived in the world of ancient paganism, finding in the medievals, particularly his beloved Dante, a way to reconcile the two, and in the Narniad a way to express that reconciled complexity. Lewis himself declared that “In Spenser, as in Milton and many others, Jove is often Jehovah incognito”. Yes, comments Ward, and “in The Lion, the divine figure [Aslan, playing the part of Christ] is Jove incognito”. Those who think they have discerned, and perhaps debunked, the Christian allegory in the Narniad have only traced the outskirts of Lewis’s ways. Perhaps Aslan’s, too.

This introduction to a masterpiece is something of a masterpiece in its own right. Lewis’s ghost (whom Lewis envisaged as a possible benign presence around Magdalene College, Cambridge) has reason to be grateful that the crucial discovery was made by someone capable of expounding it with such subtlety and depth. There are tiny blemishes, of which the reversal of the kappa and chi in the Greek word for character is perhaps the most obvious, but the overall effect is remarkable. Michael Ward has written a book whose “donegality” is the medieval scholarship, the poetic craftsmanship, the philosophical acumen and the imaginative genius of the self-consciously Jovial Lewis himself. It would be a great pity if the still prevailing Saturnine mood of our times, which has belittled and sometimes even reviled Lewis as a thinker, were to blind us to his remarkable literary, philosophical, cosmological and theological achievement.

Michael Ward

PLANET NARNIA

The seven heavens in the imagination of C. S. Lewis

347pp. Oxford University Press. Ł16.99 (US $29.95).

978 0 19 531387 1

Tom Wright is Bishop of Durham. His latest book is Justification: God’s plan and Paul’s vision, 2009. He is working on Volume Four of his series Christian Origins and the Question of God.

Eddie wrote:

Link to Michael Ward's Planet Narnia website:

http://www.planetnarnia.com/

Eddie wrote:

Loved Pauline Baynes' original Narnia illustrations:

Lucy and Mr Tumnus the faun.

Hosni wrote:

Oh, wot whimsy.

Dodgson: sexual predator

Barrie: defiler of the innocent

Lewis: flasher, general sex offender

John McLaughlin wrote:

didn't know that the medievals were ancient, and pagans to boot. THe things you pick up in lit crit.

Last edited by eddie on Sat Jun 18, 2011 4:14 am; edited 1 time in total

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Children's fiction

Re: Children's fiction

Google doodle celebrates Roger Hargreaves's Mr Men books

Google unveils 16 doodles of characters from much-loved books by English author and illustrator

Ben Quinn The Guardian, Monday 9 May 2011

The Mr Men Google doodles celebrate the 76th birthday of creator Roger Hargreaves.

The 76th birthday of Roger Hargreaves, the English author and illustrator who delighted generations of children with his Mr Men books, has been celebrated by the unveiling of no less than 16 Google doodles.

Ranging from Mr Forgetful to Little Miss Tiny, the doodle image changes each time the page is reloaded.

More than 100m books based on Hargreaves's characters have been sold worldwide in 28 countries, while five more were completed by his son Adam, but even greater world domination may yet be on the way in the form of a big screen adaptation.

Twentieth Century Fox's animation department is working on the project although it is unclear whether the Little Miss characters will feature.

Hargreaves's stories have been adapted into four animated television series, most recently airing in the UK on Channel 5 in 2008 and 2009. A total of 46 Mr Men and 33 Little Miss characters were created.

The first of the Mr Men characters is said have been created when Adam Hargreaves asked his father what a tickle looked like.

Hargreaves drew a figure with a round orange body and long, rubbery arms. Mr Tickle had been born.

Adam, who has said that the simplicity of the characters was the key to their success, took over the running of the Mr Men empire after his father died of a stroke in 1988 at the age of 53.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Google unveils 16 doodles of characters from much-loved books by English author and illustrator

Ben Quinn The Guardian, Monday 9 May 2011

The Mr Men Google doodles celebrate the 76th birthday of creator Roger Hargreaves.

The 76th birthday of Roger Hargreaves, the English author and illustrator who delighted generations of children with his Mr Men books, has been celebrated by the unveiling of no less than 16 Google doodles.

Ranging from Mr Forgetful to Little Miss Tiny, the doodle image changes each time the page is reloaded.

More than 100m books based on Hargreaves's characters have been sold worldwide in 28 countries, while five more were completed by his son Adam, but even greater world domination may yet be on the way in the form of a big screen adaptation.

Twentieth Century Fox's animation department is working on the project although it is unclear whether the Little Miss characters will feature.

Hargreaves's stories have been adapted into four animated television series, most recently airing in the UK on Channel 5 in 2008 and 2009. A total of 46 Mr Men and 33 Little Miss characters were created.

The first of the Mr Men characters is said have been created when Adam Hargreaves asked his father what a tickle looked like.

Hargreaves drew a figure with a round orange body and long, rubbery arms. Mr Tickle had been born.

Adam, who has said that the simplicity of the characters was the key to their success, took over the running of the Mr Men empire after his father died of a stroke in 1988 at the age of 53.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Children's fiction

Re: Children's fiction

Children's authors rail against Michael Gove's reading lists

Michael Rosen and Alan Gibbons line up to reject proposal for primary schools floated by national curriculum panel

James Meikle The Guardian, Saturday 7 May 2011

Michael Rosen has said he would profoundly distrust prescribed reading lists for primary school children. Photograph: Graeme Robertson for the Guardian

Children's authors are gearing up for a fight over whether schools should be given government-approved lists of books that children should have read by the time they reach a certain age.

Authors Michael Rosen and Alan Gibbons appear first in line in the latest round of what has almost become a national sport in England over the last 25 years – criticising ministers for seeking to prescribe what they see as the best texts.

The idea of replicating in primary schools what already happens in the first three years of secondary schools is being floated by a small panel of experts set up by the education secretary, Michael Gove, to review the national curriculum for five to 16-year-olds, according to the Times Educational Supplement (TES).

Rosen, a former children's laureate, told the TES : "I'm all in favour of people recommending books to each other. What I'm utterly against is some centralised list which is supposed to be the government's view or the state's view.

"If Michael Gove wants to suggest his list, that's fine. But if it is the government's list or the DfE's list, I would profoundly distrust it."

He later said: "If Michael Gove says who's recommending them [the books and authors], then that's democratic, that's the way we share ideas.

"If it's just a dictation that this is the way we read books, then we don't live in a totalitarian country, we're not in Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia, where they dictated what books you have to read."

Gibbons said: "What we need to see in schools is trust in teachers and librarians. We need a network of people who know about books and keep up to date with children's literature, who have the freedom to select books according to their pupils' backgrounds and interests."

Under the current primary curriculum children are expected to be introduced to a range of writing, including fiction, poetry, myths and plays, but there is no central list specifying books or authors.

In secondary schools, the current curriculum for 11 to 14-year-olds includes a recommended list of authors and demands that pupils study Shakespeare.

In March, Gove suggested that children from the age of 11 should be reading far more than at present – up to 50 books a year . He claimed pupils were only reading one or two books, often Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck, and invited children's authors to recommend their own favourites.

The current children's laureate, Anthony Browne, said then: "It's always good to hear that the importance of children's reading is recognised – but rather than setting an arbitrary number of books that children ought to read, I feel it's the quality of children's reading experiences that really matter. Pleasure, engagement and enjoyment of books is what counts – not simply meeting targets."

The prospect of state-directed reading has been a bone of contention for decades but arguments have been more heated since another bibliophile education secretary Kenneth Baker began laying the groundwork for the national curriculum in the mid-1980s.

Guardian writers have never been backward in recommending their own favourites. Last May a list for five to seven-year-olds included Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, by Roald Dahl, The Worst Witch, by Jill Murphy, and The Legend of Captain Crow's Teeth, by Eoin Colfer.

Inevitably JK Rowling's Harry Potter was recommended for 8 to 11-year-olds, as were CS Lewis's Narnia books and Jacqueline Wilson's The Story of Tracy Beaker.

The Department for Education said: "We want to create a world-class curriculum that will help teachers, parents and children know what children should learn at what age. We are currently reviewing all aspects of the national curriculum and will consult fully on the programmes of study when the review concludes."

The review is still in its early stages. Recommended programmes of study for English and other core subjects are expected to be put out for consultation early next year with decisions made by ministers in the spring. They will be sent to schools in September 2012.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Michael Rosen and Alan Gibbons line up to reject proposal for primary schools floated by national curriculum panel

James Meikle The Guardian, Saturday 7 May 2011

Michael Rosen has said he would profoundly distrust prescribed reading lists for primary school children. Photograph: Graeme Robertson for the Guardian

Children's authors are gearing up for a fight over whether schools should be given government-approved lists of books that children should have read by the time they reach a certain age.

Authors Michael Rosen and Alan Gibbons appear first in line in the latest round of what has almost become a national sport in England over the last 25 years – criticising ministers for seeking to prescribe what they see as the best texts.

The idea of replicating in primary schools what already happens in the first three years of secondary schools is being floated by a small panel of experts set up by the education secretary, Michael Gove, to review the national curriculum for five to 16-year-olds, according to the Times Educational Supplement (TES).

Rosen, a former children's laureate, told the TES : "I'm all in favour of people recommending books to each other. What I'm utterly against is some centralised list which is supposed to be the government's view or the state's view.

"If Michael Gove wants to suggest his list, that's fine. But if it is the government's list or the DfE's list, I would profoundly distrust it."

He later said: "If Michael Gove says who's recommending them [the books and authors], then that's democratic, that's the way we share ideas.

"If it's just a dictation that this is the way we read books, then we don't live in a totalitarian country, we're not in Nazi Germany or Soviet Russia, where they dictated what books you have to read."

Gibbons said: "What we need to see in schools is trust in teachers and librarians. We need a network of people who know about books and keep up to date with children's literature, who have the freedom to select books according to their pupils' backgrounds and interests."

Under the current primary curriculum children are expected to be introduced to a range of writing, including fiction, poetry, myths and plays, but there is no central list specifying books or authors.

In secondary schools, the current curriculum for 11 to 14-year-olds includes a recommended list of authors and demands that pupils study Shakespeare.

In March, Gove suggested that children from the age of 11 should be reading far more than at present – up to 50 books a year . He claimed pupils were only reading one or two books, often Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck, and invited children's authors to recommend their own favourites.

The current children's laureate, Anthony Browne, said then: "It's always good to hear that the importance of children's reading is recognised – but rather than setting an arbitrary number of books that children ought to read, I feel it's the quality of children's reading experiences that really matter. Pleasure, engagement and enjoyment of books is what counts – not simply meeting targets."

The prospect of state-directed reading has been a bone of contention for decades but arguments have been more heated since another bibliophile education secretary Kenneth Baker began laying the groundwork for the national curriculum in the mid-1980s.

Guardian writers have never been backward in recommending their own favourites. Last May a list for five to seven-year-olds included Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, by Roald Dahl, The Worst Witch, by Jill Murphy, and The Legend of Captain Crow's Teeth, by Eoin Colfer.

Inevitably JK Rowling's Harry Potter was recommended for 8 to 11-year-olds, as were CS Lewis's Narnia books and Jacqueline Wilson's The Story of Tracy Beaker.

The Department for Education said: "We want to create a world-class curriculum that will help teachers, parents and children know what children should learn at what age. We are currently reviewing all aspects of the national curriculum and will consult fully on the programmes of study when the review concludes."

The review is still in its early stages. Recommended programmes of study for English and other core subjects are expected to be put out for consultation early next year with decisions made by ministers in the spring. They will be sent to schools in September 2012.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Children's fiction

Re: Children's fiction

Study finds huge gender imbalace in children's literature

New research reveals male characters far outnumber females, pointing to 'symbolic annihilation of women and girls'

Alison Flood guardian.co.uk, Friday 6 May 2011 14.21 BST

Gender imbalance ... Mother reading to her children. Photograph: Bader-Butowski / WestEnd61 / Rex Features

From The Very Hungry Caterpillar to the Cat in the Hat, Peter Rabbit to Babar, children's books are dominated by male central characters, new research has found, with the gender disparity sending children a message that "women and girls occupy a less important role in society than men or boys".

Looking at almost 6,000 children's books published between 1900 and 2000, the study, led by Janice McCabe, a professor of sociology at Florida State University, found that males are central characters in 57% of children's books published each year, with just 31% having female central characters. Male animals are central characters in 23% of books per year, the study found, while female animals star in only 7.5%.

Published in the April issue of Gender & Society, the study, Gender in Twentieth-Century Children's Books, looked at Caldecott award-winning books, the well-known US book series Little Golden Books and extensive book listing the Children's Catalog. Just one Caldecott winner (1985's Have You Seen My Duckling? following a mother duck on a search for her baby) has had a standalone female character since the award was established in 1938. Books with male animals were more than two-and-a-half times more common across the century than those with female animals, the authors said.

Although the gender disparity came close to disappearing by the 1990s for human characters in children's books, with a ration of 0.9 to 1 for child characters and 1.2 to 1 for adult characters, it remained for animal characters, with a "significant disparity" of nearly two to one. The study found that the 1930s to 1960s, the period between waves of feminist activism, "exhibits greater disparities than earlier and later periods".

"The messages conveyed through representation of males and females in books contribute to children's ideas of what it means to be a boy, girl, man, or woman. The disparities we find point to the symbolic annihilation of women and girls, and particularly female animals, in 20th-century children's literature, suggesting to children that these characters are less important than their male counterparts," write the authors. "The disproportionate numbers of males in central roles may encourage children to accept the invisibility of women and girls and to believe they are less important than men and boys, thereby reinforcing the gender system."

The authors of the study said that even gender-neutral animal characters are frequently labelled as male by mothers reading to their children, which only "exaggerates the pattern of female underrepresentation". "These characters could be particularly powerful, and potentially overlooked, conduits for gendered messages," they said. "The persistent pattern of disparity among animal characters may reveal a subtle kind of symbolic annihilation of women disguised through animal imagery."

The Carnegie medal-winning children's author Melvin Burgess, whose own novels regularly feature female central characters, pointed to the "truism in publishing that girls will read books that have boy heroes, whereas boys won't read books that have girl heroes".

"Boys are far more gender-specific," he said. "I guess the challenge is to write books for boys that have female characters in, that the boys will relate to. It's a sad fact that books written for boys do tend to fall rapidly into the old stereotypes, and the action figures, baddies etc are generally male, and very straightforward males as well. I try to get away from that. It's a been a while since I wrote an action-type book, but I am working on one now and it does involve four young people – two girls, two boys – and I always try to make my girls really stand out."

But it's not only an absence of female central characters which is a problem in children's books, believes former children's laureate Anne Fine: it's how the women are represented when they do appear. "Publishers rightly take care to put in positive images of a mix of races, but seem not to even notice when they use stereotypical and way out-of-date images of women," she said. "In modern classics such as Owl Babies and Hooray for Fish! it's always the mother, never the dad, whom the child ends up wanting and needing. God forbid each book should try to cover all the 'issues'; but we do need a bit of balance. Children's authors should make an effort to do a bit of role widening. I try. You wouldn't notice, but in every single one of my books, the male can cook. In The Country Pancake, my farmer just happens to be a female. And on and on."

The notion, meanwhile, that boys only read books by and about males does "become a self-fulfilling prophecy", Fine said. "More worryingly, in these new lists of recommended books for boys, there's a heap of fantasy and violence, very little humour (except for the poo and bum sort), and almost no family novels at all. If you offer boys such a narrow view of the world, and don't offer them novels that show them dealing with normal family feelings, they will begin to think this sort of stuff is not for them."

Fine believes that "women should be giving a much beadier eye to the books they share with children ... It's important to balance much loved old-fashioned classics with stuff that evens things up a bit and reflects women's current role in the world," she said.

But Carnegie medal winner Frank Cottrell Boyce feels that "women have an influence in children's literature that belies the numbers".

"I'm sure this is because brilliant women like Edith Nesbitt, who in a fairer society might have gone into politics or science, have instead poured all their brilliance into writing. The result is that over several years, women have produced really important – really, really important – children's fiction that has helped define eras and people," he said. "I'm thinking right back to Little Women – which has provided women with a roadmap of identity for generations– and Anne of Green Gables. But also of the way women from Enid Blyton and Richmal Crompton – incomparably our best prose stylist and paradoxically the writer who defined boyhood – to JK Rowling, Jacqueline Wilson and Stephenie Meyer, have totally dominated popular narrative culture. So never mind the quantity, feel the quality."

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

New research reveals male characters far outnumber females, pointing to 'symbolic annihilation of women and girls'

Alison Flood guardian.co.uk, Friday 6 May 2011 14.21 BST

Gender imbalance ... Mother reading to her children. Photograph: Bader-Butowski / WestEnd61 / Rex Features

From The Very Hungry Caterpillar to the Cat in the Hat, Peter Rabbit to Babar, children's books are dominated by male central characters, new research has found, with the gender disparity sending children a message that "women and girls occupy a less important role in society than men or boys".

Looking at almost 6,000 children's books published between 1900 and 2000, the study, led by Janice McCabe, a professor of sociology at Florida State University, found that males are central characters in 57% of children's books published each year, with just 31% having female central characters. Male animals are central characters in 23% of books per year, the study found, while female animals star in only 7.5%.

Published in the April issue of Gender & Society, the study, Gender in Twentieth-Century Children's Books, looked at Caldecott award-winning books, the well-known US book series Little Golden Books and extensive book listing the Children's Catalog. Just one Caldecott winner (1985's Have You Seen My Duckling? following a mother duck on a search for her baby) has had a standalone female character since the award was established in 1938. Books with male animals were more than two-and-a-half times more common across the century than those with female animals, the authors said.

Although the gender disparity came close to disappearing by the 1990s for human characters in children's books, with a ration of 0.9 to 1 for child characters and 1.2 to 1 for adult characters, it remained for animal characters, with a "significant disparity" of nearly two to one. The study found that the 1930s to 1960s, the period between waves of feminist activism, "exhibits greater disparities than earlier and later periods".

"The messages conveyed through representation of males and females in books contribute to children's ideas of what it means to be a boy, girl, man, or woman. The disparities we find point to the symbolic annihilation of women and girls, and particularly female animals, in 20th-century children's literature, suggesting to children that these characters are less important than their male counterparts," write the authors. "The disproportionate numbers of males in central roles may encourage children to accept the invisibility of women and girls and to believe they are less important than men and boys, thereby reinforcing the gender system."

The authors of the study said that even gender-neutral animal characters are frequently labelled as male by mothers reading to their children, which only "exaggerates the pattern of female underrepresentation". "These characters could be particularly powerful, and potentially overlooked, conduits for gendered messages," they said. "The persistent pattern of disparity among animal characters may reveal a subtle kind of symbolic annihilation of women disguised through animal imagery."

The Carnegie medal-winning children's author Melvin Burgess, whose own novels regularly feature female central characters, pointed to the "truism in publishing that girls will read books that have boy heroes, whereas boys won't read books that have girl heroes".

"Boys are far more gender-specific," he said. "I guess the challenge is to write books for boys that have female characters in, that the boys will relate to. It's a sad fact that books written for boys do tend to fall rapidly into the old stereotypes, and the action figures, baddies etc are generally male, and very straightforward males as well. I try to get away from that. It's a been a while since I wrote an action-type book, but I am working on one now and it does involve four young people – two girls, two boys – and I always try to make my girls really stand out."

But it's not only an absence of female central characters which is a problem in children's books, believes former children's laureate Anne Fine: it's how the women are represented when they do appear. "Publishers rightly take care to put in positive images of a mix of races, but seem not to even notice when they use stereotypical and way out-of-date images of women," she said. "In modern classics such as Owl Babies and Hooray for Fish! it's always the mother, never the dad, whom the child ends up wanting and needing. God forbid each book should try to cover all the 'issues'; but we do need a bit of balance. Children's authors should make an effort to do a bit of role widening. I try. You wouldn't notice, but in every single one of my books, the male can cook. In The Country Pancake, my farmer just happens to be a female. And on and on."

The notion, meanwhile, that boys only read books by and about males does "become a self-fulfilling prophecy", Fine said. "More worryingly, in these new lists of recommended books for boys, there's a heap of fantasy and violence, very little humour (except for the poo and bum sort), and almost no family novels at all. If you offer boys such a narrow view of the world, and don't offer them novels that show them dealing with normal family feelings, they will begin to think this sort of stuff is not for them."

Fine believes that "women should be giving a much beadier eye to the books they share with children ... It's important to balance much loved old-fashioned classics with stuff that evens things up a bit and reflects women's current role in the world," she said.

But Carnegie medal winner Frank Cottrell Boyce feels that "women have an influence in children's literature that belies the numbers".

"I'm sure this is because brilliant women like Edith Nesbitt, who in a fairer society might have gone into politics or science, have instead poured all their brilliance into writing. The result is that over several years, women have produced really important – really, really important – children's fiction that has helped define eras and people," he said. "I'm thinking right back to Little Women – which has provided women with a roadmap of identity for generations– and Anne of Green Gables. But also of the way women from Enid Blyton and Richmal Crompton – incomparably our best prose stylist and paradoxically the writer who defined boyhood – to JK Rowling, Jacqueline Wilson and Stephenie Meyer, have totally dominated popular narrative culture. So never mind the quantity, feel the quality."

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Children's fiction

Re: Children's fiction

Eeyore: Literature's archetypal outsider

Never has a gloomy loner been so much loved. It won't cheer him up, but let's wish him happy birthday anyway

Eeyore, as seen in the film version

You may not know it, but today is Eeyore's birthday. And if there's one thing that upsets Eeyore more than anything, it's people forgetting his birthday. Traditionally Eeyore might receive a popped balloon from Piglet, or an empty honey jar from Pooh. But since AA Milne's gloomy donkey turns 140 today – which is Very Old Indeed – I think we should surprise him by celebrating his status as a truly great literary character.

The Winnie-the-Pooh stories are part of the fabric of our lives. We grow up reading them, then we read them to our children. But while each character is loveable, Eeyore seems to have a special place in our hearts. We are drawn helplessly towards him; we recognise something deeply human in his gloomy outlook. His sadness is our sadness. He's an Everyman; an Every-donkey.

In literary terms, Eeyore is the archetypal outsider. The other animals – Pooh, Piglet, Owl and the rest – dwell happily within Hundred Acre Wood, knocking on each others' doors, having tea and embarking on adventures. But not Eeyore. He lives on the other side of the stream in his Gloomy Place – marked on the map as "Rather Boggy and Sad". Rather than venture out to see others, he waits for them to pass through his field, which doesn't happen often. "I have my friends," he notes ruefully. "Somebody spoke to me only yesterday. And was it last week or the week before that Rabbit bumped into me and said 'Bother!' The Social Round. Always something going on."

So what does Eeyore spend most of his time doing? Like all great outsiders, he Thinks – and he takes great pains to distinguish himself from the other animals for this. ("They haven't got Brains, any of them, only grey fluff that's blown into their heads by mistake..."). There he is in his lonely corner of the forest, sometimes thinking sadly to himself, "Why?", and sometimes "Wherefore?" – and sometimes not quite knowing what he's thinking at all. While the other animals amble contentedly through their daily lives, Eeyore wrestles with these questions alone.

The tragedy is that all this thinking doesn't make Eeyore happy. As Benjamin Hoff has argued in his marvellous book The Tao of Pooh, Eeyore can't enjoy life because his mind is clouded with thoughts that cut him off from the world around him – which, in the case of Hundred Acre Wood, is a beautiful one. He can't live the simple, spontaneous and joyful life of Pooh – a Bear of Very Little Brain, maybe, but the happiest character in the wood because of it.

So the riddle of Eeyore is this: why, despite his many failings, do we love him so much?

I think it's partly because, as well as being the most depressing individual in the Pooh books, he is also the funniest. Melancholy often teeters on the brink of absurdity, and Eeyore regularly falls over the edge. Take the classic scene in The House at Pooh Corner when Eeyore tumbles into the stream after the irrepressible Tigger bounces up behind him and takes him by surprise. The image of Eeyore, floating around in circles with his feet in the air, trying to maintain his sombre demeanour, is desperately funny and sad.

And then there's his truly glorious sarcasm (of which there are too many instances to catalogue here), whose hilarity is heightened further by the way that it sails straight over the other characters' heads.

But the key thing that makes Eeyore a great character is that essential literary ingredient: conflict. Eeyore is profoundly conflicted. He craves love – indeed, he's always lamenting his outsider status – but he struggles to give and receive it. When it's offered to him, he puts out his hoof and waves it away. There are many occasions when Pooh and Piglet, who love Eeyore unconditionally, pay him a visit only to be greeted with a barrage of sarcasm. Nowhere is this more poignantly displayed than the scene in The House at Pooh Corner where Piglet realises that Eeyore has never had a bunch of violets picked for him. When he finds Eeyore to deliver the bunch, however, he gets shooed away. "Tomorrow," says Eeyore. "Or the next day."

It's this conflict that humanises Eeyore, and makes his plight a sympathetic one. Despite his unyielding misery – or perhaps because of it – we all love Eeyore, so let's celebrate his birthday. I'm sure it would make him happy: eyes down, tail swishing, mumbling through a mouthful of thistles... "Thanks for noticing me."

Posted by Chris Cox Monday 9 May 2011 13.01 BST guardian.co.uk

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Never has a gloomy loner been so much loved. It won't cheer him up, but let's wish him happy birthday anyway

Eeyore, as seen in the film version

You may not know it, but today is Eeyore's birthday. And if there's one thing that upsets Eeyore more than anything, it's people forgetting his birthday. Traditionally Eeyore might receive a popped balloon from Piglet, or an empty honey jar from Pooh. But since AA Milne's gloomy donkey turns 140 today – which is Very Old Indeed – I think we should surprise him by celebrating his status as a truly great literary character.

The Winnie-the-Pooh stories are part of the fabric of our lives. We grow up reading them, then we read them to our children. But while each character is loveable, Eeyore seems to have a special place in our hearts. We are drawn helplessly towards him; we recognise something deeply human in his gloomy outlook. His sadness is our sadness. He's an Everyman; an Every-donkey.

In literary terms, Eeyore is the archetypal outsider. The other animals – Pooh, Piglet, Owl and the rest – dwell happily within Hundred Acre Wood, knocking on each others' doors, having tea and embarking on adventures. But not Eeyore. He lives on the other side of the stream in his Gloomy Place – marked on the map as "Rather Boggy and Sad". Rather than venture out to see others, he waits for them to pass through his field, which doesn't happen often. "I have my friends," he notes ruefully. "Somebody spoke to me only yesterday. And was it last week or the week before that Rabbit bumped into me and said 'Bother!' The Social Round. Always something going on."

So what does Eeyore spend most of his time doing? Like all great outsiders, he Thinks – and he takes great pains to distinguish himself from the other animals for this. ("They haven't got Brains, any of them, only grey fluff that's blown into their heads by mistake..."). There he is in his lonely corner of the forest, sometimes thinking sadly to himself, "Why?", and sometimes "Wherefore?" – and sometimes not quite knowing what he's thinking at all. While the other animals amble contentedly through their daily lives, Eeyore wrestles with these questions alone.

The tragedy is that all this thinking doesn't make Eeyore happy. As Benjamin Hoff has argued in his marvellous book The Tao of Pooh, Eeyore can't enjoy life because his mind is clouded with thoughts that cut him off from the world around him – which, in the case of Hundred Acre Wood, is a beautiful one. He can't live the simple, spontaneous and joyful life of Pooh – a Bear of Very Little Brain, maybe, but the happiest character in the wood because of it.

So the riddle of Eeyore is this: why, despite his many failings, do we love him so much?

I think it's partly because, as well as being the most depressing individual in the Pooh books, he is also the funniest. Melancholy often teeters on the brink of absurdity, and Eeyore regularly falls over the edge. Take the classic scene in The House at Pooh Corner when Eeyore tumbles into the stream after the irrepressible Tigger bounces up behind him and takes him by surprise. The image of Eeyore, floating around in circles with his feet in the air, trying to maintain his sombre demeanour, is desperately funny and sad.

And then there's his truly glorious sarcasm (of which there are too many instances to catalogue here), whose hilarity is heightened further by the way that it sails straight over the other characters' heads.

But the key thing that makes Eeyore a great character is that essential literary ingredient: conflict. Eeyore is profoundly conflicted. He craves love – indeed, he's always lamenting his outsider status – but he struggles to give and receive it. When it's offered to him, he puts out his hoof and waves it away. There are many occasions when Pooh and Piglet, who love Eeyore unconditionally, pay him a visit only to be greeted with a barrage of sarcasm. Nowhere is this more poignantly displayed than the scene in The House at Pooh Corner where Piglet realises that Eeyore has never had a bunch of violets picked for him. When he finds Eeyore to deliver the bunch, however, he gets shooed away. "Tomorrow," says Eeyore. "Or the next day."

It's this conflict that humanises Eeyore, and makes his plight a sympathetic one. Despite his unyielding misery – or perhaps because of it – we all love Eeyore, so let's celebrate his birthday. I'm sure it would make him happy: eyes down, tail swishing, mumbling through a mouthful of thistles... "Thanks for noticing me."

Posted by Chris Cox Monday 9 May 2011 13.01 BST guardian.co.uk

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Children's fiction

Re: Children's fiction

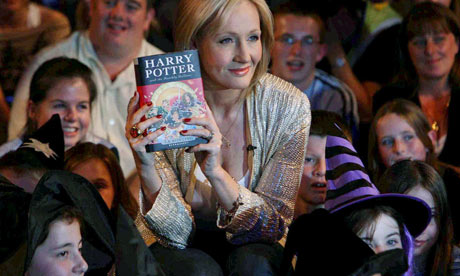

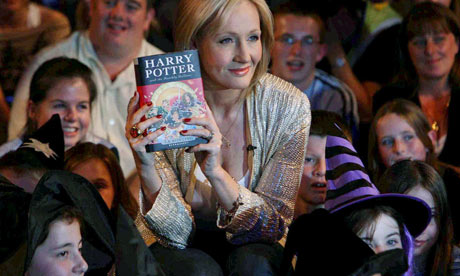

JK Rowling reveals her favourite Harry Potter character

Oddly enough, it's the boy wizard himself

Alison Flood guardian.co.uk, Monday 16 May 2011 12.02 BST

JK Rowling at a promotional event for Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. Photograph: EPA

She caused a scandal when she killed him off at the end of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, but Albus Dumbledore is still the character JK Rowling would most like to have dinner with, the bestselling children's author has revealed.

As her publisher Bloomsbury launched a global search to find the world's favourite Harry Potter character, Rowling said that her own most-favoured creation is the lightning-scarred young Harry himself. "I believe I am unusual in this, Ron is generally more popular (I love him too, though)," said the author. "Now that I have finished writing the books, the character I would most like to meet for dinner is Dumbledore. We would have a lot to discuss, and I would love his advice; I think that everyone would like a Dumbledore in their lives."

The author has said in the past that Hermione Granger resembles her the most. "I have often said that Hermione is a bit like me when I was younger," she writes on her website. "I think I was seen by other people as a right little know-it-all, but I hope that it is clear that underneath Hermione's swottiness there is a lot of insecurity and a great fear of failure (as shown by her Boggart in Prisoner of Azkaban)."

From Severus Snape to the Dark Lord Voldemort himself, Bloomsbury has pulled together a list of 40 characters from the Harry Potter books and is asking fans to vote online for their favourite. If, among assorted Weasleys, Potters and Malfoys, elves and owls, a character is found to be missing, then readers can ask for it to be added to the list. The poll opens on 16 May and runs until 26 August, with the winning character to be unveiled on 30 August.

The Harry Potter books have sold more than 400m copies worldwide, said Bloomsbury, and have been translated into 69 languages.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Oddly enough, it's the boy wizard himself

Alison Flood guardian.co.uk, Monday 16 May 2011 12.02 BST

JK Rowling at a promotional event for Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. Photograph: EPA

She caused a scandal when she killed him off at the end of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, but Albus Dumbledore is still the character JK Rowling would most like to have dinner with, the bestselling children's author has revealed.

As her publisher Bloomsbury launched a global search to find the world's favourite Harry Potter character, Rowling said that her own most-favoured creation is the lightning-scarred young Harry himself. "I believe I am unusual in this, Ron is generally more popular (I love him too, though)," said the author. "Now that I have finished writing the books, the character I would most like to meet for dinner is Dumbledore. We would have a lot to discuss, and I would love his advice; I think that everyone would like a Dumbledore in their lives."

The author has said in the past that Hermione Granger resembles her the most. "I have often said that Hermione is a bit like me when I was younger," she writes on her website. "I think I was seen by other people as a right little know-it-all, but I hope that it is clear that underneath Hermione's swottiness there is a lot of insecurity and a great fear of failure (as shown by her Boggart in Prisoner of Azkaban)."

From Severus Snape to the Dark Lord Voldemort himself, Bloomsbury has pulled together a list of 40 characters from the Harry Potter books and is asking fans to vote online for their favourite. If, among assorted Weasleys, Potters and Malfoys, elves and owls, a character is found to be missing, then readers can ask for it to be added to the list. The poll opens on 16 May and runs until 26 August, with the winning character to be unveiled on 30 August.

The Harry Potter books have sold more than 400m copies worldwide, said Bloomsbury, and have been translated into 69 languages.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Children's fiction

Re: Children's fiction

About gender bias in children's books:

I've noticed that the books teachers assign to students to read in middle school and high school are oriented to boys.

I figure this is because the teachers feel it is harder to keep boys interested in reading than girls so books are assigned that boys will like.

It really bugs me.