Science Fiction

+3

felix

Dick Fitzwell

eddie

7 posters

Page 1 of 2

Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Science Fiction

Science Fiction

Iain M Banks: Science fiction is no place for dabblers

Iain M Banks guardian.co.uk, Friday 13 May 2011 09.56 BST

Iain M Banks near his home by the Forth Bridge Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

Consider a publishing bash of some sort, probably in London. A respected but still-young-enough-to-be-promising author of literary fiction (that's the sort who tends to get reviewed in serious newspapers such as the Guardian, is generally published in both hardback and then B-format paperback and might even stand an outside chance of nabbing a Man Booker prize) approaches their agent – or editor; either is acceptable – all bright eyed and enthusiastic for reasons which go beyond a couple of glasses of wine or a recent good review and tells the agent/editor: "I've just had this great idea; I've got to write this!"

The agent/editor immediately assumes a look of fascinated interest, while internally recalibrating his or her wariness threshold to "Caution: Incoming". "Right," the author says, "prepare for something entirely new, fresh and completely different: a novel, written by me . . . which might look like what people call a 'detective story' –" (both sets of index and middle fingers may be needed by the author at this point to indicate the presence of the quotation marks enclosing these words, though the slight but unmistakable accompanying sneer is actually more important), "– but which isn't really, because it's me who's writing it, see? Anyway, it's set in . . . an English country house," the author says, with a dramatic flourish which strongly implies the agent/editor certainly wouldn't have been expecting that detail. Actually the agent/editor may have started to go a little glassy-eyed at this point, but no matter. "And there's a sort of weekend houseparty going on, you see? And there are all sorts of people there, like a retired colonel and a famous lady clairvoyant and an angry young man and a flighty young thing – isn't this just a fascinating cast of characters? – but then there's an unexpected snow storm and they're completely cut off, and then . . . there's a murder! Yes; a murder! But it turns out one of the guests is a famous amateur detective, and . . ." By now, of course, the agent/editor will be staring at the author, possibly open mouthed if they're still relatively inexperienced and so retain any sort of faith in the inherent wisdom and literary acumen of your average – or even exceptional – writer ". . . and then the twist at the end! I almost don't want to tell you because it'll spoil it for you first time you read it, but I've got to tell you, it's so brilliant!" The author pauses momentarily here, to let the agent/editor say something like: "Why, no then, don't! I've heard enough! Let's do the deal right here; we'll take your last contract and just add a zero at the end!" but, in the absence of something like this, plunges on with: "It turns out the murderer is . . . the butler!"

Now, even the most gifted literary author will be sufficiently aware of the clichés of the detective story not to let an initial burst of enthusiasm for a new idea involving any of them get beyond the limits of his or her own cranium, and even if they were foolish enough to suggest something on these lines to their agent or editor they'd immediately be informed that It's Been Done . . . in fact, It's Been Done to the Point of Being a Joke . . . and so all the above never happens.

Or at least, it never happens quite as described; substitute the phrase "science fiction" for the word "detective", delete the 1930s murder-mystery novel clichés and insert some 30s science fiction clichés and I get the impression this scenario has indeed played out, and not just once but several times, and the agent/editor has – bizarrely – entirely shared the enthusiasm of their author, so that, a year or two later, yet another science fiction novel which isn't really a science fiction novel – but, like, sort of is at the same time? – hits the shelves, usually to decent and only slightly sniffy reviews (sometimes, to be fair, to quite excitable reviews) while, off-stage, barely heard, howls of laughter and derision issue from the science fiction community.

The point is that science fiction is a dialogue, a process. All writing is, in a sense; a writer will read something – perhaps something quite famous, even a classic – and think "But what if it had been done this way instead . . . ?" And, standing on the shoulders of that particular giant, write something initially similar but developmentally different, so that the field evolves and further twists and turns are added to how stories are told as well as to the expectations and the knowledge of pre-existing literary patterns readers bring to those stories. Science fiction has its own history, its own legacy of what's been done, what's been superseded, what's so much part of the furniture it's practically part of the fabric now, what's become no more than a joke . . . and so on. It's just plain foolish, as well as comically arrogant, to ignore all this, to fail to do the most basic research. In a literature so concerned with social as well as technical innovation, with the effects of change – incremental as well as abrupt – on individual humans and humanity as whole, this is a grievous, fundamentally hubristic mistake to commit.

Science fiction can never be a closed shop where only those already steeped in its culture are allowed to practise, but, as with most subjects, if you're going to enter the dialogue it does help to know at least a little of what you're talking about, and it also helps, by implication, not to dismiss everything that's gone before as not worth bothering with because, well, it's just Skiffy and the poor benighted wretches have never been exposed to a talent the like of mine before . . .

In the end, writing about what you know – that hoary and potentially limiting, even stultifying piece of advice – might be best seen as applying to the type of story you're thinking of writing rather than to the details of what happens within it and perhaps, with that in mind, a better precept might be to write about what you love, rather than what you have a degree of contempt for but will deign to lower yourself to, just to show the rest of us how it's done.

However, let's be positive about this. The very fact that entirely respectable writers occasionally feel drawn to write what is perfectly obviously science fiction – regardless of either their own protestations or those of their publishers – shows that a further dialogue between genres is possible, especially if we concede that literary fiction may be legitimately regarded as one as well.

It's certainly desirable.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Iain M Banks guardian.co.uk, Friday 13 May 2011 09.56 BST

Iain M Banks near his home by the Forth Bridge Photograph: Murdo Macleod for the Guardian

Consider a publishing bash of some sort, probably in London. A respected but still-young-enough-to-be-promising author of literary fiction (that's the sort who tends to get reviewed in serious newspapers such as the Guardian, is generally published in both hardback and then B-format paperback and might even stand an outside chance of nabbing a Man Booker prize) approaches their agent – or editor; either is acceptable – all bright eyed and enthusiastic for reasons which go beyond a couple of glasses of wine or a recent good review and tells the agent/editor: "I've just had this great idea; I've got to write this!"

The agent/editor immediately assumes a look of fascinated interest, while internally recalibrating his or her wariness threshold to "Caution: Incoming". "Right," the author says, "prepare for something entirely new, fresh and completely different: a novel, written by me . . . which might look like what people call a 'detective story' –" (both sets of index and middle fingers may be needed by the author at this point to indicate the presence of the quotation marks enclosing these words, though the slight but unmistakable accompanying sneer is actually more important), "– but which isn't really, because it's me who's writing it, see? Anyway, it's set in . . . an English country house," the author says, with a dramatic flourish which strongly implies the agent/editor certainly wouldn't have been expecting that detail. Actually the agent/editor may have started to go a little glassy-eyed at this point, but no matter. "And there's a sort of weekend houseparty going on, you see? And there are all sorts of people there, like a retired colonel and a famous lady clairvoyant and an angry young man and a flighty young thing – isn't this just a fascinating cast of characters? – but then there's an unexpected snow storm and they're completely cut off, and then . . . there's a murder! Yes; a murder! But it turns out one of the guests is a famous amateur detective, and . . ." By now, of course, the agent/editor will be staring at the author, possibly open mouthed if they're still relatively inexperienced and so retain any sort of faith in the inherent wisdom and literary acumen of your average – or even exceptional – writer ". . . and then the twist at the end! I almost don't want to tell you because it'll spoil it for you first time you read it, but I've got to tell you, it's so brilliant!" The author pauses momentarily here, to let the agent/editor say something like: "Why, no then, don't! I've heard enough! Let's do the deal right here; we'll take your last contract and just add a zero at the end!" but, in the absence of something like this, plunges on with: "It turns out the murderer is . . . the butler!"

Now, even the most gifted literary author will be sufficiently aware of the clichés of the detective story not to let an initial burst of enthusiasm for a new idea involving any of them get beyond the limits of his or her own cranium, and even if they were foolish enough to suggest something on these lines to their agent or editor they'd immediately be informed that It's Been Done . . . in fact, It's Been Done to the Point of Being a Joke . . . and so all the above never happens.

Or at least, it never happens quite as described; substitute the phrase "science fiction" for the word "detective", delete the 1930s murder-mystery novel clichés and insert some 30s science fiction clichés and I get the impression this scenario has indeed played out, and not just once but several times, and the agent/editor has – bizarrely – entirely shared the enthusiasm of their author, so that, a year or two later, yet another science fiction novel which isn't really a science fiction novel – but, like, sort of is at the same time? – hits the shelves, usually to decent and only slightly sniffy reviews (sometimes, to be fair, to quite excitable reviews) while, off-stage, barely heard, howls of laughter and derision issue from the science fiction community.

The point is that science fiction is a dialogue, a process. All writing is, in a sense; a writer will read something – perhaps something quite famous, even a classic – and think "But what if it had been done this way instead . . . ?" And, standing on the shoulders of that particular giant, write something initially similar but developmentally different, so that the field evolves and further twists and turns are added to how stories are told as well as to the expectations and the knowledge of pre-existing literary patterns readers bring to those stories. Science fiction has its own history, its own legacy of what's been done, what's been superseded, what's so much part of the furniture it's practically part of the fabric now, what's become no more than a joke . . . and so on. It's just plain foolish, as well as comically arrogant, to ignore all this, to fail to do the most basic research. In a literature so concerned with social as well as technical innovation, with the effects of change – incremental as well as abrupt – on individual humans and humanity as whole, this is a grievous, fundamentally hubristic mistake to commit.

Science fiction can never be a closed shop where only those already steeped in its culture are allowed to practise, but, as with most subjects, if you're going to enter the dialogue it does help to know at least a little of what you're talking about, and it also helps, by implication, not to dismiss everything that's gone before as not worth bothering with because, well, it's just Skiffy and the poor benighted wretches have never been exposed to a talent the like of mine before . . .

In the end, writing about what you know – that hoary and potentially limiting, even stultifying piece of advice – might be best seen as applying to the type of story you're thinking of writing rather than to the details of what happens within it and perhaps, with that in mind, a better precept might be to write about what you love, rather than what you have a degree of contempt for but will deign to lower yourself to, just to show the rest of us how it's done.

However, let's be positive about this. The very fact that entirely respectable writers occasionally feel drawn to write what is perfectly obviously science fiction – regardless of either their own protestations or those of their publishers – shows that a further dialogue between genres is possible, especially if we concede that literary fiction may be legitimately regarded as one as well.

It's certainly desirable.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Science Fiction

Re: Science Fiction

The stars of modern SF pick the best science fiction

To celebrate the opening of the British Library's science fiction exhibition Out of this World, we asked leading SF writers to choose their favourite novel or author in the genre

The Guardian, Saturday 14 May 2011

Vision of the future ... detail from UFO over the City, 1980 (oil on canvas) by Michael Buhler. Photograph: Private collection/The Bridgeman Art Library

Brian Aldiss

Star Maker by Olaf Stapledon (1937)

It requires little sophistry to consider Daniel Defoe's immortal Robinson Crusoe as a metaphor for a man stranded on an alien planet. Crusoe is an exile, and exile has proved a perennial theme within the genre of science fiction. Of all its great themes, lingering on the fringes of comprehension is Star Maker, by Olaf Stapledon (1882-1950). Stapledon was an exile, his childhood spent between Egypt and England. Star Maker is both illuminated and darkened by a feeling of not belonging, the essence of exile.

It was published in 1937, when it received a rather chilly reception; the public did not know what to make of it. If it was influenced by Milton's Paradise Lost, it was doubtless also formed by the terror of the war against Nazi Germany, which was about to descend upon us.

The opening sentence of Star Maker is: "One night when I had tasted bitterness I went out on to the hill." The lonely voyager through the cosmos finds world after world, some worlds inhabited by races of bird-clouds, some by insect-like creatures, each of whose swarms form the bodies of a single mind. Such is the mystery of creation; what of the spirit itself? "When I tried to probe the depths of my own being, I found impenetrable mystery." Something of which we all know but can hardly enunciate – certainly not as Stapledon does. The speaker, on its spiritual odyssey throughout creation, gains a cold, almost incomprehensible confrontation with the Star Maker itself.

What can we make of this terrible thing creating and controlling entire galaxies?

"All passions, it seemed, were compromised within the spirit's temper: but mastered, icily gripped within the cold, clear, crystal ecstasy of contemplation."

Stapledon's book embraces the firmament. Read it and you will be forever changed.

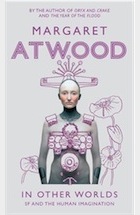

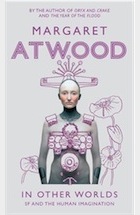

Margaret Atwood

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury (1953)

As a young teenager, I devoured Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 by flashlight. It gave me nightmares. In the early 1950s television was just rolling forth, and people sat mesmerised in front of their flickering sets, eating their dinners off TV trays. Surely, it was said, "the family" was doomed, since the traditional dinnertime was obsolete. Films and books too were about to fall victim to the new all-consuming medium. My own parents refused to get a TV, so I had to sneak over to friends' houses to gape at The Ed Sullivan Show. But when not doing that, I fed my reading addiction, whenever, however, whatever. Hence Fahrenheit 451. In this riveting book, books themselves are condemned – all books. The very act of reading is considered detrimental to social order because it causes people to think, and then to distrust the authorities. Instead of books the public is offered conformity via four-wall TV, with the sound piped directly into their heads via shell-shaped earbuds (a brilliant proleptic leap on the part of Bradbury). Montag, the main character, is a "Fireman": his job is to burn each and every book uncovered by the state's spies and informers. But little by little Montag gets converted to reading, and finally joins the underground: a dedicated band of individuals sworn to preserve world literature by becoming the living repositories of the books they have memorised.

Fahrenheit 451 predated Marshall McLuhan and his theories about how media shape people, not just the reverse. We interact with our creations, and they themselves act upon us. Now that we're in the midst of a new wave of innovative media technologies, it's time to reread this classic, which poses the eternal questions: who and how do we want to be?

Stephen Baxter

Hothouse by Brian Aldiss (1961)

Billions of years hence, the sun hangs swollen and unmoving in the sky. Across Earth's sunward face a riotous jungle is dominated by a single continent-spanning banyan tree. And in the canopy, Gren, an adult at nine years old, the size of a small monkey, is one of the last humans: "[Earth] was no longer a place for mind. It was a place for growth, for vegetables. It was a hothouse."

When I first read Hothouse as a teenager I was thrilled by the vivid detail of Brian Aldiss's fecund far-future jungle, set within a grander Stapledonian vision of an Earth blooming in the light of its long evolutionary afternoon. The vividness surely derives from Aldiss's own youthful experiences; he served in the chaotic second world war theatres of Borneo and Sumatra. Meanwhile the book's depiction of a devolved mankind in a wistful far-futurity recalls scenes from HG Wells's The Time Machine – Aldiss has always been a great Wellsian. This is a very British evocation. In the hands of an American author there might have been some way out; Gren might have been allowed to discover ancient machineries, to reconquer the Earth. Aldiss, like Wells, is pitiless: "Man had rolled up his affairs and retired to the trees from whence he came." But the book was embraced by the Americans too; it won a Hugo award, science fiction's Oscar, named for Hugo Gernsback, king of the US pulp-fiction magazines.

Looking at Hothouse now I can see foreshadows of Aldiss's later works; for example, it is an audacious exercise in world-building, like the Helliconia trilogy of the 1980s. And I can admire its technical audacity. Its depiction of not-quite-human consciousness recalls Golding's The Inheritors. Hugely inventive, straddling genre forms and literary aspirations, and at once chilling and consoling in its long perspective, Aldiss's great book thrills me now as much as it did when I first discovered it some four decades ago.

Lauren Beukes

Watchmen by Alan Moore (1986-7)

It took me years to read Watchmen. Every time I'd get to the men in tights and the giant naked blue guy, I'd think, "Ack! Superhero comic!" and put it down again. It wasn't that I was against comics. I'd read 2000AD Monthly religiously since 1989 and Alan Moore's The Ballad of Halo Jones, about a girl from an interplanetary ghetto who wanted to get "out", was my favourite series of all. But I liked the dark, twisty stuff that had something to say about the world and superhero comics seemed tediously codified with no room for moral ambiguity. I should have known better. What Moore does best, even at his silliest or most obtusely philosophical, is subvert. He uses story to crack open the dark places of the human soul like a crab shell, revealing the pasty meat within, and then pokes it with a cattleprod to see it writhe.

He's the kind of writer who makes you feel very smart (Kitty Genovese and the moral bankruptcy of crowds in Watchmen, for example) and very stupid (a dozen obscure Victorian literature references interwoven into every page of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen) at the same time. He pushes the medium. Every panel, every background detail, every interlude, whether a vaudeville song or a beat-style short story or seemingly wholly unrelated pirate horror comic, counts. He stretches the boundaries of storytelling in ways other writers wouldn't attempt, let alone pull off – and does it with a ferocious social conscience that challenges everything we are.

And when he has a mind to, when he's not off on some grand mal meditation on the nature of magic or sexual desire or what stories mean, Moore tells the perfect story. Inventive. Surprising. Original. Utterly devastating. From being the comic I couldn't read, Watchmen became the narrative I hold up as what fiction can be.

John Clute

City by Clifford D Simak (1952)

We know better now, of course. But they still entrance us, the old page-turners from the glory days of American SF, half a century or so ago, when the world was full of futures we were never going to have. In the mid-1940s, when he began to publish the episodes that would be assembled as City in 1952, Clifford Simak, a Minneapolis-based journalist and author, could still carry us away with the dream that cars and pollution and even the great cities of the world – "Huddling Place", the title of one of these tales, is his own derisory term for them – would soon be brushed off the map by Progress, leaving nothing behind but tasteful exurbs filled with middle-class nuclear families living the good life, with fishing streams and greenswards sheltering each home from the stormy blast.

Fortunately, Simak soon gets past this demented vision of a near-future world saved by technological fixes, a dementia common then to SF writers and gurus and politicians alike, and launches into an astonishingly eventful narrative of the next 10,000 years as seen through the eyes of one family and the immortal robot Jenkins, and all told with a weird pastoral serenity that for a kid like me seemed near to godlike. In its course City touches on almost everything dear to 1940s SF, and to me remembering. Robots. Genetic Engineering. Space. Jupiter. Domed cities. Keeps. Hiveminds. Matter transmission. Telepathy. Parallel worlds. Paranormal empathy. Mutants. Supermen. It's all there, and, thanks to Simak's skilled hand at the wheel, it's all in place: suave, sibylline, swift. The whole is framed as a series of legends told by the uplifted Dogs who have replaced the human race, now gone for ever. They have been bred not to kill. At the end, only Jenkins remains to keep them from learning how to repeat history and die.

It all seemed immensely sad and wise then, but fun. It still does.

Jon Courtenay Grimwood

Light by M John Harrison (2002)

Light is the kind of novel other writers read and think: "Why don't I just give up and go home?" That was certainly my first reaction on reading its mix of coldly perfect prose and attractively twisted insanity. It's also the only book to bring me unpleasantly close to sympathising with a serial killer. But this is M John Harrison: so antihero Michael Kearney is a mathematically brilliant, dice-throwing, reality-changing hyper-intelligent serial killer haunted by a horse-skulled personal demon.

Harrison's genius is to tie Kearney's narrative thread to those of Seria Mau – a far-future girl existing in harmony with White Cat, her spaceship, surfing a part of the galaxy known as the Kefahuchi Tract – and Chinese Ed, a sleazy if likeable cyberpunky chancer with a passion for virtual sex.

This is not a kind book, or even a particularly likeable book. But then I suspected it was never intended to be, and the author wouldn't want the kind of people who want to like characters as his readers anyway. What it is is stunningly written, meticulously plotted, hallucinogenically realised and brutally honest. No one who reads it could doubt that Harrison might win the Booker if he could be bothered.

Light is also the book that novelist and critic Adam Roberts was so sure would win the Arthur C Clarke award, he offered to change his name to Adam Van Hoogenroberts if it didn't. We're still waiting . . .

Andrew Crumey

The Brick Moon by Edward Everett Hale (1870)

The term "science fiction" hadn't been invented in 1870, when the American magazine Atlantic Monthly published the first part of Edward Everett Hale's delightfully eccentric novella The Brick Moon. Readers lacked a ready-made pigeonhole for it, confronted by a fantasy about a group of visionaries who decide to make a 200-ft wide sphere of house-bricks, paint it white, and launch it into orbit.

Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon had appeared five years earlier, so Hale's work was not unprecendented, but while Verne chose to send his voyagers aloft using a giant cannon, Hale opts for the equally unfeasible but somehow more pleasing solution of a giant flywheel.

Hale gives technical details and calculations to support the plausibility of the venture. He even works out the total cost of the bricks ($60,000). There is an info-dump about latitude and longitude: the brick moon is designed to orbit from pole to pole so that people anywhere can determine their location by observing it. There are ruminations and speculations – and, to be honest, quite a few longeurs, even in a compass of only 25,000 words. But crucially there is humour. The brick moon gets launched accidentally with some people inside. Those left behind watch through telescopes as the travellers make their own little world, communicating by writing signs in big letters. They grow plants, hold church services, and their brick moon becomes a tiny, charming parody of Earth.

The Brick Moon did not appear in book form until 1899, when Hale was in his 70s, by which time HG Wells had appeared on the scene and Hale was slipping into obscurity. Nowadays he is little more than a footnote, remembered for having been the first to imagine artificial satellites. But what makes The Brick Moon still worth reading is not scientific vision, but sheer joyful quirkiness.

William Gibson

The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester (1957)

The idea of literary "favourites" makes me uneasy, but Alfred Bester's 1957 novel The Stars My Destination has remained very close to the top of my list for science fiction, since I first discovered it as a child (though I much prefer Bester's original title Tiger, Tiger, which was evidently deemed too arthouse for the trade). Bester was an urbane and successful Mad Av dandy, an anomaly among American SF writers of his day, and his best work is deliciously redolent of the brains and flash and bustle of postwar Manhattan. TSMD is a retelling of Dumas's The Count of Monte Cristo, its protagonist one Gully Foyle, lumpenprole untermensch turned revenging angel in a world utterly transformed by the discovery that teleportation is a natural and teachable human talent. Perfectly surefooted, elegantly pulpy, dizzying in its pace and sweep, TSMD is still as much fun as anything I've ever read. When I was lifting the literary equivalent of weights, in training for my own first novel, it was my talisman: evidence of how many different kinds of ass one quick narrative could kick. And that sheen of exuberant postwar modernism? They just aren't making any more of that.

Ursula K Le Guin

Virginia Woolf (1882–1941)

You can't write science fiction well if you haven't read it, though not all who try to write it know this. But nor can you write it well if you haven't read anything else. Genre is a rich dialect, in which you can say certain things in a particularly satisfying way, but if it gives up connection with the general literary language it becomes a jargon, meaningful only to an ingroup. Useful models may be found quite outside the genre. I learned a lot from reading the ever-subversive Virginia Woolf.

I was 17 when I read Orlando. It was half-revelation, half-confusion to me at that age, but one thing was clear: that she imagined a society vastly different from our own, an exotic world, and brought it dramatically alive. I'm thinking of the Elizabethan scenes, the winter when the Thames froze over. Reading, I was there, saw the bonfires blazing in the ice, felt the marvellous strangeness of that moment 500 years ago – the authentic thrill of being taken absolutely elsewhere.

How did she do it? By precise, specific descriptive details, not heaped up and not explained: a vivid, telling imagery, highly selected, encouraging the reader's imagination to fill out the picture and see it luminous, complete.

In Flush, Woolf gets inside a dog's mind, that is, a non-human brain, an alien mentality – very science-fictional if you look at it that way. Again what I learned was the power of accurate, vivid, highly selected detail. I imagine Woolf looking down at the dog asleep beside the ratty armchair she wrote in and thinking what are your dreams? and listening . . . sniffing the wind . . . after the rabbit, out on the hills, in the dog's timeless world.

Useful stuff, for those who like to see through eyes other than our own.

Russell Hoban

HP Lovecraft (1890–1937)

The main thing about HP Lovecraft is his too-muchness; he never uses three adjectives when five will do, but he writes words that haunt the memory: "In his house at R'lyeh dead Cthulhu waits dreaming." My recall of the multiplication table is shaky but those words disquiet me today as freshly as when I first read them.

Where did dead Cthulhu come from? Why did he rise up from the murky depths of Lovecraft's mental ocean? I say it's because there is a need for him and the rest of the maestro's monsters. Why is there such an appetite, such a hunger for scary stories and films? I think there is a primal horror in us. From where? From the Big Bang when Something came out of Nothing? From the nothingness we must become at life's end? I don't know, but I know it's there and we like to dress it up with a bolt through its neck or a black rubber alien suit; or as Cthulhu. Get a load of this: "A pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque and scaly body with rudimentary wings", with elements of "an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature", "but it was the general outline of the whole that made it most shockingly frightful". Close your eyes and try to imagine this creature of non-Darwinian evolution. Just the look of this bozo is already a major horror, and we're not even into the story yet. While he's dead and dreaming in his house at R'lyeh ("Dun Foamin"?) his Cthulhuvibes are spreading worldwide and causing strange rites and observances here and there. Lovecraft is not everybody's mug of Ovaltine but I have always found him horribly cosy.

Liz Jensen

The Day of the Triffids by John Wyndham (1951)

As a teenager, one of my favourite haunts was Oxford's Botanical Gardens. I'd head straight for the vast heated greenhouses, where I'd pity my adolescent plight, chain-smoke, and glory in the insane vegetation that burgeoned there. The more rampant, brutally spiked, poisonous, or cruel to insects a plant was, the more it appealed to me. I'd shove my butts into their root systems. They could take it. My librarian mother disapproved mightily of the fags but when under interrogation I confessed where I'd been hanging out – hardly Sodom and Gomorrah – she spotted a literary opportunity, and slid John Wyndham's The Day of the Triffids my way. I read it in one sitting, fizzing with the excitement of recognition. I knew the triffids already: I'd spent long hours in the jungle with them, exchanging gases. Wyndham loved to address the question that triggers every invented world: the great "What if . . ." What if a carnivorous, travelling, communicating, poison-spitting oil-rich plant, harvested in Britain as biofuel, broke loose after a mysterious "comet-shower" blinded most of the population? That's the scenario faced by triffid-expert Bill Masen, who finds himself a sighted man in a sightless nation. Cataclysmic change established, cue a magnificent chain reaction of experimental science, physical and political crisis, moral dilemmas, new hierarchies, and hints of a new world order. Although the repercussions of an unprecedented crisis and Masen's personal journey through the new wilderness form the backbone of the story, it's the triffids that root themselves most firmly in the reader's memory. Wyndham described them botanically, but he left enough room for the reader's imagination to take over. The result being that everyone who reads The Day of the Triffids creates, in their mind's eye, their own version of fiction's most iconic plant. Mine germinated in an Oxford greenhouse, in a cloud of cigarette smoke.

Hari Kunzru

Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (1972)

Soviet-era Russian science fiction deserves a wider audience in English. The Strugatsky brothers collaborated on numerous novels and stories, the best known of which is this, partly because it was filmed by Andrei Tarkovsky as Stalker, in 1977. The novel takes place 10 years after a mysterious alien visitation, which seems to have no rational explanation. No one saw the visitors. Their presence caused disease and blindness in the areas where they landed. Now, in the six "Zones", the laws of physics (and, seemingly, of reality) are disturbed by anomalies, and littered with inexplicable, deadly wreckage. Only a few brave "stalkers" risk their lives to enter the zones to gather alien artefacts for sale. Some of these artefacts offer the promise of extraordinary powers. Unlike Tarkovsky's film, which concentrates on the hallucinatory, vacated landscape of the zones, the novels portray a society adapting to an inexplicable, terrifying event, an eruption of the unknown. Though written in 1971 and published in English in 1977, the novel was heavily bowdlerised by Soviet censors, and an authoritative text wasn't available in Russian until 2000. It's a book with an extraordinary atmosphere – and a demonstration of how science fiction, by using a single bold central metaphor, can open up the possibilities of the novel.

Kelly Link

Diana Wynne Jones (1934–2011)

I can't pick just one book by Diana Wynne Jones. She wrote so many books, all of them essential, and funny, and weird, and true. She mixed up fantasy and science fiction and the domestic so that unhappy families and awkward adolescents got smooshed up, quite believably, with mythological figures, extraterrestrial powers, and all other sorts of dangerous beasties. I was already a science-fiction reader before I found Dogsbody. But I might have outgrown science fiction quickly, moved on to books about horses and girls and high schools, if it weren't for books such as Dogsbody and The Homeward Bounders and Archer's Goon, and if it weren't for characters such as Kathleen, who rescues a puppy and falls in love with a star, and Jamie, who spies on a dangerous game that They are playing, and Howard, with his two very complicated families.

Wynne Jones's books are often literally about other worlds, but her characters belong very firmly to this one. They are eccentric, flamboyant, pragmatic, lonely, sometimes selfish, often stubborn, always recognisable. How they navigate the territory that they find themselves in is, I suppose, a kind of metaphor for the process of growing up. But I'm grown up now, and have a child of my own, and I rely on her books, her pinprick insights into familial relationships, her astonishing way of seeing the worlds.

Ken MacLeod

A Canticle for Liebowitz by Walter M Miller Jr (1960)

Walter M Miller Jr's A Canticle for Liebowitz is one of the few SF novels to have won lasting mainstream literary acceptance. It is also one of the very few SF novels to present the Roman Catholic church in a kindly light.

Its premise is straightforward: centuries after our civilisation self-destructs in a nuclear war, the church preserves fragments of its scientific knowledge in the desert monasteries of a battered America. A Jewish convert, the engineer Liebowitz, played a major part in saving books from the anti-science backlash after the war. These ancient texts – the Memorabilia – spark a new Renaissance, to eventually reboot an industrial civilisation more advanced than ours. This civilisation, in its turn . . . but you're ahead of me, yes? So is the church, which this time takes its remnant – and the vastly expanded Memorabilia – to the stars.

This millennial tale is told in close-up. We follow monks reverently copying diagrams they don't understand, and venerating relics we know to be detritus. We hear litanies in which Fallout is the name of a demon. Dramatic ironies multiply as the first of the new scientists scoffs at an abbot's quaint belief in evolution. And although the successor civilisation has interstellar colonies, the texture of its daily, earthly life is the same as ours, or rather that of the 1960s: cars, television, communications satellites, cold war, nuclear tensions. This isn't a failure of imagination: Miller was, as his many short stories show, well capable of imagining far-future worlds. It's a dramatic device to bring us to the most chillingly science-fictional recognition of all: that our civilisation, too, is one of post-catastrophe recovery.

We smile at the monks of the Order of Liebowitz, laboriously inking in a blueprint instead of just copying the lines, but the joke is on us. We're Rome, rebooted.

China Miéville

The Island of Doctor Moreau by HG Wells (1896)

In his own thoroughly strange 1946 novel Life Comes to Seathorpe, Neil Bell appropriates the term "rare books" to designate members of a new, dissident literary canon. A book, he says, is rare if "[i]t stood by itself . . . among all books . . . [and] was in a way unique." Of those mooncalf, ill-fitting, ineffably strange examples he lists, his first and most outstanding is The Island of Doctor Moreau.

He is right. This short, merciless novel of a vivisectionist's efforts to remake beasts as humans is a shattering text. A peerless piece of science fictional horror, saturated with wrongness all the more powerful for its cold prose, it doesn't evoke so much as demand visceral, social, philosophical dread. Wells was always politically the most interesting and cantankerous of the Fabians, but, as so often, the critiques, contradictions and catastrophes in his fiction go further by far than those in his self-consciously political non-fiction. Like all worthwhile fiction, the book evades allegorical reduction, but among the phenomena it is "about", one, ostentatiously, is colonialism. It oscillates in extraordinary superposition between two countervailing critiques of empire: one we might roughly gloss as reactionary – that those colonised cannot be "civilised"; the other more radical – that the colonial project is a nightmarish House of Pain.

Like its earlier close relative Frankenstein, Moreau is regularly traduced as a warning against hubris, of the dangers of Meddling With Things that Should Be Left Alone, and so on. In fact, both texts are rebukes to that tedious and craven fingerwagging – though, published a mere biblical lifespan apart, in poignantly opposed ways. Where for Shelley monstrousness arises out of Frankenstein's refusal to engage with the social reality of what he has done, for Wells, it is brutal, ongoing engagement itself that is the cause of the horror. Frankenstein warns of disaster if we fail the Enlightenment: in nihilist Fabian terror, Moreau cries out that the Enlightenment has failed.

Michael Moorcock

The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester (1956)

Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress was the first book I bought with my own money. It made such a strong impression on me that, still a convinced agnostic, I started out believing a book should have at least two levels and contain some sort of moral element. Christian learning to be a decent man by facing the dangers and temptations of the world was a pretty good lesson for a would-be writer. I searched out other visionary texts. Milton's Paradise Lost was the natural successor and a subtler one, for here the villain is enormously attractive and appeals to all our emotions, including pity. Blake made up the initial three. Magnificent visions, strong moral voices. Christian's adventures are dreamlike and powerful and possess some tremendous prose. The book contains everything I came to look for in imaginative fiction, even when an author denied he had no specific moral purpose. In science fiction such as Alfred Bester's The Stars My Destination, the author refuses allegory (though not idealism) and insists all he's doing is telling a romantic story based on The Count of Monte Cristo, set in the future, but I already found a little more to it when I read it in Paris at the age of 16, sitting outside Shakespeare and Co, having earned the money to buy it from busking. Bester's predictions included a world where all the powerful aristocratic families carry the names of Heinz, Chrysler, Sara Lee and most of the brands we are familiar with; a world where democracy has been subverted and strange cults, reflecting aspects of our modern world, have grown up. For me, it made as strong an impression as Bunyan and reminds me why the best science fiction still contains, as in Ballard, vivid imagery and powerful prose coupled to a strong moral vision.

Patrick Ness

Quicksilver by Neal Stephenson (2003)

Bypassing all requirements of "importance" or "influence" or "classic status" – though I'd argue that it has all of those things – I've simply gone for the sci-fi novel I enjoyed reading the most. Neal Stephenson's Quicksilver is a huge (900-plus pages), brilliant, Arthur C Clarke award-winning story about the founding of modern science. It's also – incredibly – outrageously good fun.

Packed with research, a mind-boggling array of real historical characters from Isaac Newton to William of Orange, and digressions on anything from philosophy to finance to cryptography, Quicksilver manages to never be obnoxious about its smarts. The destinies of fictional early scientist Daniel Waterhouse, "King of the Vagabonds" Jack Shaftoe, and former-harem-girl-turned-economics-wizard Eliza improbably (yet inevitably) weave together through court intrigue, Le Roi himself and the founding of the Royal Society, but even that doesn't begin to cover Quicksilver's joyous sprawl. It's funny, cheerfully violent, and eye-wateringly ribald. You'll also thank your lucky stars you never had a kidney stone in 1661.

Exhilaration is too rare in fiction. That rush of delight, that desperate need to get back to the pages to find out what happens next, particularly in a novel as clever as this one, is worth cherishing. When Quicksilver first came out, I described it as less a book, more a place to move into and raise a family. I still believe that. The best science fiction, indeed the best fiction, contains whole worlds. You'll be hard-pressed to find one as splendidly entertaining as Quicksilver's.

Audrey Niffenegger

Time and Again: An Illustrated Novel by Jack Finney (1970)

Time and Again is an original; there is nothing quite like it. It is the story of Si Morley, a commercial artist who is drawing a piece of soap one ordinary day in 1970 when a mysterious man from the US Army shows up at his Manhattan office to recruit him for a secret government project. The project turns out to involve time travel; the idea is that artists and other imaginative people can be trained (by self-hypnosis) to imagine themselves so completely in the past that they actually go there. Si finds himself sitting in an apartment in the famous Dakota building pretending to be in the past . . . and ends up in the Manhattan of 1882.

The story makes good use of paradox and the butterfly effect, but its greatest charms lie in Si's good-humoured observations of old New York and the love story that gradually develops between Si and the beautiful Julia, who doesn't believe Si when he tells her he's a time traveller. Time and Again is laden with authentic period photos and newspaper engravings which Jack Finney works into the narrative gracefully. When I first read WG Sebald's Austerlitz, a very different book in both subject and mood, I realised that it owed something to Finney's innovative use of pictures as evidence within a novel. Really, the pictures seem to say, this did happen, I saw it, don't you believe me? The pictures cause us, the readers, to sway slightly as we suspend our disbelief; they look like proof of something we know is unprovable. Isn't it?

There is something wistful about time travel stories as they age: 1970 is now 41 years past. A lot happened in those years, and these characters are blissfully unaware of the future. I get a little shiver of nostalgia in the book's opening pages: gee, people used to go to offices and sit at drawing boards and get paid to draw soap. What a world. Perhaps if I could imagine it completely enough, I could visit . . . but no. I'll just read about it, again and again.

Christopher Priest

The Voices of Time by JG Ballard (1960)

When he died two years ago, JG Ballard was widely celebrated for his novels, and rightly. Empire of the Sun, an account of his wartime internment in Shanghai, brought him a Spielberg movie and a worldwide audience, but he also wrote the remarkable novels Crash, High-Rise, Cocaine Nights and many more. Inspired by Dalí, De Chirico, William Burroughs and Jean Genet, his talent was unique: his vivid, surprising and often beautiful prose was put to the creation of dreamlike and sometimes shocking images, while telling a deceptively straightforward narrative.

Ballard began writing in 1955 (he was in his mid-20s) and his first serious novel, The Drowned World, did not appear until seven years later. Before that he produced a stream of astonishing short stories, which to long-term admirers of Ballard's writing are among his finest fiction. In them he explored for the first time many of the themes which in new guises were to coil their way through his better known later work. Supreme in these stories is an extraordinary novella, The Voices of Time, first published in 1960 and later the title story of a collection.

The plot almost defies summary. An imminent global disaster is seen from the viewpoint of a group of sleep-addicted scientists, slowly going mad in a desert installation surrounded by salt lakes, where genetic experiments have bred mutant animals to resist the radiated atmosphere. Meanwhile, a countdown to the end of the universe has begun, a suicidal madman engraves a mandala on the floor of an emptied swimming pool, a sleep-deprived astronomer cruises the dunes in a white Packard saloon, a raven-haired temptress named Coma plays the men off against each other. Somehow it all seems to make crazy and brilliant sense. I have read the story a dozen times, never actually understood it, but also have never failed to draw inspiration and encouragement from Ballard's pellucid writing and the amazing and surreal images.

Alastair Reynolds

The City and the Stars by Arthur C Clarke (1956)

Everyone has their touchstone text, but for me it must be Arthur C Clarke's The City and the Stars. By the time I encountered it, at the age of 12 or 13 (I recall picking it out of a rotating bookstand, near the door of a bookshop in the Lake District, during one of those rain-sodden childhood holidays), I was already familiar with Clarke as the sober-minded chronicler of near future space exploration. In scores of short stories, and in novels such as Earthlight, 2001: A Space Odyssey and Rendezvous with Rama, Clarke took me to the Moon, Mars and beyond – always in that same benign, sceptical, calm voice of scientific reason.

The City and the Stars was a magnificent shock to the system. Rather than being set a hundred or two hundred years hence, and rather than dealing with astronauts and implacable alien artefacts, The City slams us billions of years into the future, telescoping entire aeons and ages into mere eyeblinks. It's about Diaspar, the last city on Earth. And what an astonishing, beautiful creation it is. Rarely, for a novel written half a century ago (and which owed its origin to a work predating the second world war), The City's core ideas still feel bold and far-reaching. Diaspar's citizens entertain themselves in virtual realities, are born and reborn time and again from computer archives, their personalities remixed from iteration to iteration, and they can organise and edit their own memories at will. Their placid lives are perfect, their utopian city endlessly self-renewing. And yet . . . they have no interest in what lies beyond Diaspar's awesome walls. Until a citizen is born, Alvin, who seems never to have existed before. And Alvin very much wants to know what lies outside.

Clarke was a scientist, and his work sits squarely in the tradition of "hard SF" – a largely detestable term, but we're stuck with it – which is to say, science fiction with one eye on strict scientific plausibility. Much hard SF is stylistically dry, with little concern for character or what one might consider the finer literary virtues. There was rather more to Clarke than mere nuts and bolts description, though. On a good day, he could rise to the genuinely poetic – Diaspar is a lovely, evocative name – and there are countless passages in his work where a genuine sense of wonder is achieved. The City and the Stars is full of them, and it remains my favourite novel of the deep, distant future.

Adam Roberts

Dune by Frank Herbert (1965)

Not my favourite SF novel, but my gateway drug: Frank Herbert's Dune. When I pick it up now I tend to see only its flaws (Herbert's leaden prose, incapable of concision; his limited, and essentialist and in some cases homophobic characterisation). But if I cast my mind back to my 10-year-old self, and remember the effect it had on me, I'm able to remind myself that the book's strengths eclipse its shortcomings. It achieves a genuine grandeur, something that has a lot to do with the brilliance of Herbert's mise-en-scène – the desert-world of Arrakis, the beautiful, imagination-snaring barrenness of his locations. Herbert is sometimes praised for his "worldbuilding", but this isn't quite right (on the level of worldbuilding the novel has notable flaws, not least the absence of any means of oxygenating the planetary atmosphere). Rather, Dune's deserts function eloquently as metaphor and topographical signifier, empty enough of conventional geographical features – the frontispiece map is a blank page barely sullied by dotted-lines showing occasional features – to provide an uncluttered aesthetic and imaginative space. The novel presciently anticipated the sort of environmentalist concerns, "ecology" in the idiom of the 1960s, that have subsequently become culturally central – Dune was, indeed, the first novel with an ecological theme to have a significant impact.

In a sense, Herbert's triumph in Dune is precisely finding simple but eloquent tropes for important but complex subjects such as these. His future society is clothed in the simplified feudal lineaments of a medieval fantasy – computers are banished by religious edict, society is strictly hierarchical – which enables him to sketch large questions of human social and political interaction. Even now I'm an adult, Herbert's sandworms still move through the deserts of my imagination.

Kim Stanley Robinson

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K Le Guin (1969)

One of my favorite novels is The Left Hand of Darkness, by Ursula K Le Guin. For more than 40 years I've been recommending this book to people who want to try science fiction for the first time, and it still serves very well for that. One of the things I like about it is how clearly it demonstrates that science fiction can have not only the usual virtues and pleasures of the novel, but also the startling and transformative power of the thought experiment.

In this case, the thought experiment is quickly revealed: "The king was pregnant," the book tells us early on, and after that we learn more and more about this planet named Winter, stuck in an ice age, where the humans are most of the time neither male nor female, but with the potential to become either. The man from Earth investigating this situation has a lot to learn, and so do we; and we learn it in the course of a thrilling adventure story, including a great "crossing of the ice". Le Guin's language is clear and clean, and has within it both the anthropological mindset of her father Alfred Kroeber, and the poetry of stories as magical things that her mother Theodora Kroeber found in native American tales. This worldly wisdom applied to the romance of other planets, and to human nature at its deepest, is Le Guin's particular gift to us, and something science fiction will always be proud of. Try it and see – you will never think about people in quite the same way again.

Tricia Sullivan

Octavia E Butler (1947–2006)

I was teaching in New York when I came across Octavia E Butler's Kindred in a secondary-school catalogue of novels recommended to support diversity. It caught my attention because Butler was described as a science-fiction writer. I thought I was familiar with science fiction, but I'd never heard of her – nor have a great many other readers, I suspect. For many years, Butler was the sole African-American woman novelist in science fiction. Kindred tells the wrenching and unforgettable story of a young black woman who time-travels and saves the life of her slaveholder ancestor, but it is, in Butler's words, "a grim fantasy", not science fiction.

Beginning in the 1970s, Butler wrote three sequences of novels: the Patternist books, the Lilith's Brood series and the Parable novels (incomplete at her tragic death in 2006). Critically respected, she won the Hugo and Nebula awards, received a Clarke nomination, the PEN lifetime achievement award and a MacArthur Foundation "genius" grant. A serious writer working in a field that is seldom taken seriously, Butler addressed biological control, gender, humanity's relationship with aliens, genetics and even the development of a fictional religion. Her narratives leave space for the reader's involvement while exploring the nature of change. They gaze unflinchingly on power dynamics. "Who will rule? Who will lead? Who will define, refine, confine, design? Who will dominate? All struggles are essentially power struggles," Butler stated, "and most are no more intellectual than two rams knocking their heads together." Butler's writing is courageous, stimulating and infused with a rare purity of intention. Crushingly, she died at the height of her powers. Bloodchild and Other Stories is a good place to begin discovering her work.

Scarlett Thomas

Neuromancer by William Gibson (1984)

I first read Neuromancer when I was living in Torquay in 1999. For me it was a time of cheap junk food, cigarettes, videogames, arcades and Hello Kitty hairbands. The novel was just the right thing for the time, and its post-industrial Japanese wastelands didn't feel so remote. There's so much trivia about Neuromancer, and everything it inspired, from the name "Microsoft" to the Matrix films – perhaps even the whole internet. But what I've always loved about Gibson are the same things I love about Jane Austen and Chekhov. Gibson uses small, precise details to build a world in which people are defined by their contemporary technologies, fashions and material culture. In Neuromancer, as in Gibson's other books, you always know what the characters are wearing. Here, one character turns up dressed in a "suit of gunmetal silk and a simple bracelet of platinum on either wrist". A woman's hairband "might have represented microcircuits, or a city map".

I'm surprised Gibson is seen as a highly masculine writer, given the focus on fashion and the consistently romantic plots. Yes, there's hot RAM (the fact that people are trading RAM in megabytes in the "future" is one of very few details that date the novel), a military outfit called Screaming Fist and simstim consoles. But there's also the uber-cool razorgirl Molly, kicking ass in her "cherry red cowboy boots". Gibson's prose style is in the tradition of Chekhov, Carver, Chandler, Burroughs and Hemingway. Lots of verbs, lots of nouns – things – as opposed to feelings, over-explanation and exposition. Before I began writing The End of Mr Y, I put three books on my desk as lucky charms, and this was one of them. My novel isn't cyberpunk, but I wanted my readers to feel something of what I felt when I first read Neuromancer.

Out of this World: Science Fiction But Not As You Know It is open from 20 May-25 September 2011 at the British Library, London. Admission to the exhibition is free. For more information call 0207 412 7332 or visit www.bl.uk

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

To celebrate the opening of the British Library's science fiction exhibition Out of this World, we asked leading SF writers to choose their favourite novel or author in the genre

The Guardian, Saturday 14 May 2011

Vision of the future ... detail from UFO over the City, 1980 (oil on canvas) by Michael Buhler. Photograph: Private collection/The Bridgeman Art Library

Brian Aldiss

Star Maker by Olaf Stapledon (1937)

It requires little sophistry to consider Daniel Defoe's immortal Robinson Crusoe as a metaphor for a man stranded on an alien planet. Crusoe is an exile, and exile has proved a perennial theme within the genre of science fiction. Of all its great themes, lingering on the fringes of comprehension is Star Maker, by Olaf Stapledon (1882-1950). Stapledon was an exile, his childhood spent between Egypt and England. Star Maker is both illuminated and darkened by a feeling of not belonging, the essence of exile.

It was published in 1937, when it received a rather chilly reception; the public did not know what to make of it. If it was influenced by Milton's Paradise Lost, it was doubtless also formed by the terror of the war against Nazi Germany, which was about to descend upon us.

The opening sentence of Star Maker is: "One night when I had tasted bitterness I went out on to the hill." The lonely voyager through the cosmos finds world after world, some worlds inhabited by races of bird-clouds, some by insect-like creatures, each of whose swarms form the bodies of a single mind. Such is the mystery of creation; what of the spirit itself? "When I tried to probe the depths of my own being, I found impenetrable mystery." Something of which we all know but can hardly enunciate – certainly not as Stapledon does. The speaker, on its spiritual odyssey throughout creation, gains a cold, almost incomprehensible confrontation with the Star Maker itself.

What can we make of this terrible thing creating and controlling entire galaxies?

"All passions, it seemed, were compromised within the spirit's temper: but mastered, icily gripped within the cold, clear, crystal ecstasy of contemplation."

Stapledon's book embraces the firmament. Read it and you will be forever changed.

Margaret Atwood

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury (1953)

As a young teenager, I devoured Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451 by flashlight. It gave me nightmares. In the early 1950s television was just rolling forth, and people sat mesmerised in front of their flickering sets, eating their dinners off TV trays. Surely, it was said, "the family" was doomed, since the traditional dinnertime was obsolete. Films and books too were about to fall victim to the new all-consuming medium. My own parents refused to get a TV, so I had to sneak over to friends' houses to gape at The Ed Sullivan Show. But when not doing that, I fed my reading addiction, whenever, however, whatever. Hence Fahrenheit 451. In this riveting book, books themselves are condemned – all books. The very act of reading is considered detrimental to social order because it causes people to think, and then to distrust the authorities. Instead of books the public is offered conformity via four-wall TV, with the sound piped directly into their heads via shell-shaped earbuds (a brilliant proleptic leap on the part of Bradbury). Montag, the main character, is a "Fireman": his job is to burn each and every book uncovered by the state's spies and informers. But little by little Montag gets converted to reading, and finally joins the underground: a dedicated band of individuals sworn to preserve world literature by becoming the living repositories of the books they have memorised.

Fahrenheit 451 predated Marshall McLuhan and his theories about how media shape people, not just the reverse. We interact with our creations, and they themselves act upon us. Now that we're in the midst of a new wave of innovative media technologies, it's time to reread this classic, which poses the eternal questions: who and how do we want to be?

Stephen Baxter

Hothouse by Brian Aldiss (1961)

Billions of years hence, the sun hangs swollen and unmoving in the sky. Across Earth's sunward face a riotous jungle is dominated by a single continent-spanning banyan tree. And in the canopy, Gren, an adult at nine years old, the size of a small monkey, is one of the last humans: "[Earth] was no longer a place for mind. It was a place for growth, for vegetables. It was a hothouse."

When I first read Hothouse as a teenager I was thrilled by the vivid detail of Brian Aldiss's fecund far-future jungle, set within a grander Stapledonian vision of an Earth blooming in the light of its long evolutionary afternoon. The vividness surely derives from Aldiss's own youthful experiences; he served in the chaotic second world war theatres of Borneo and Sumatra. Meanwhile the book's depiction of a devolved mankind in a wistful far-futurity recalls scenes from HG Wells's The Time Machine – Aldiss has always been a great Wellsian. This is a very British evocation. In the hands of an American author there might have been some way out; Gren might have been allowed to discover ancient machineries, to reconquer the Earth. Aldiss, like Wells, is pitiless: "Man had rolled up his affairs and retired to the trees from whence he came." But the book was embraced by the Americans too; it won a Hugo award, science fiction's Oscar, named for Hugo Gernsback, king of the US pulp-fiction magazines.

Looking at Hothouse now I can see foreshadows of Aldiss's later works; for example, it is an audacious exercise in world-building, like the Helliconia trilogy of the 1980s. And I can admire its technical audacity. Its depiction of not-quite-human consciousness recalls Golding's The Inheritors. Hugely inventive, straddling genre forms and literary aspirations, and at once chilling and consoling in its long perspective, Aldiss's great book thrills me now as much as it did when I first discovered it some four decades ago.

Lauren Beukes

Watchmen by Alan Moore (1986-7)

It took me years to read Watchmen. Every time I'd get to the men in tights and the giant naked blue guy, I'd think, "Ack! Superhero comic!" and put it down again. It wasn't that I was against comics. I'd read 2000AD Monthly religiously since 1989 and Alan Moore's The Ballad of Halo Jones, about a girl from an interplanetary ghetto who wanted to get "out", was my favourite series of all. But I liked the dark, twisty stuff that had something to say about the world and superhero comics seemed tediously codified with no room for moral ambiguity. I should have known better. What Moore does best, even at his silliest or most obtusely philosophical, is subvert. He uses story to crack open the dark places of the human soul like a crab shell, revealing the pasty meat within, and then pokes it with a cattleprod to see it writhe.

He's the kind of writer who makes you feel very smart (Kitty Genovese and the moral bankruptcy of crowds in Watchmen, for example) and very stupid (a dozen obscure Victorian literature references interwoven into every page of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen) at the same time. He pushes the medium. Every panel, every background detail, every interlude, whether a vaudeville song or a beat-style short story or seemingly wholly unrelated pirate horror comic, counts. He stretches the boundaries of storytelling in ways other writers wouldn't attempt, let alone pull off – and does it with a ferocious social conscience that challenges everything we are.

And when he has a mind to, when he's not off on some grand mal meditation on the nature of magic or sexual desire or what stories mean, Moore tells the perfect story. Inventive. Surprising. Original. Utterly devastating. From being the comic I couldn't read, Watchmen became the narrative I hold up as what fiction can be.

John Clute

City by Clifford D Simak (1952)

We know better now, of course. But they still entrance us, the old page-turners from the glory days of American SF, half a century or so ago, when the world was full of futures we were never going to have. In the mid-1940s, when he began to publish the episodes that would be assembled as City in 1952, Clifford Simak, a Minneapolis-based journalist and author, could still carry us away with the dream that cars and pollution and even the great cities of the world – "Huddling Place", the title of one of these tales, is his own derisory term for them – would soon be brushed off the map by Progress, leaving nothing behind but tasteful exurbs filled with middle-class nuclear families living the good life, with fishing streams and greenswards sheltering each home from the stormy blast.

Fortunately, Simak soon gets past this demented vision of a near-future world saved by technological fixes, a dementia common then to SF writers and gurus and politicians alike, and launches into an astonishingly eventful narrative of the next 10,000 years as seen through the eyes of one family and the immortal robot Jenkins, and all told with a weird pastoral serenity that for a kid like me seemed near to godlike. In its course City touches on almost everything dear to 1940s SF, and to me remembering. Robots. Genetic Engineering. Space. Jupiter. Domed cities. Keeps. Hiveminds. Matter transmission. Telepathy. Parallel worlds. Paranormal empathy. Mutants. Supermen. It's all there, and, thanks to Simak's skilled hand at the wheel, it's all in place: suave, sibylline, swift. The whole is framed as a series of legends told by the uplifted Dogs who have replaced the human race, now gone for ever. They have been bred not to kill. At the end, only Jenkins remains to keep them from learning how to repeat history and die.

It all seemed immensely sad and wise then, but fun. It still does.

Jon Courtenay Grimwood

Light by M John Harrison (2002)

Light is the kind of novel other writers read and think: "Why don't I just give up and go home?" That was certainly my first reaction on reading its mix of coldly perfect prose and attractively twisted insanity. It's also the only book to bring me unpleasantly close to sympathising with a serial killer. But this is M John Harrison: so antihero Michael Kearney is a mathematically brilliant, dice-throwing, reality-changing hyper-intelligent serial killer haunted by a horse-skulled personal demon.

Harrison's genius is to tie Kearney's narrative thread to those of Seria Mau – a far-future girl existing in harmony with White Cat, her spaceship, surfing a part of the galaxy known as the Kefahuchi Tract – and Chinese Ed, a sleazy if likeable cyberpunky chancer with a passion for virtual sex.

This is not a kind book, or even a particularly likeable book. But then I suspected it was never intended to be, and the author wouldn't want the kind of people who want to like characters as his readers anyway. What it is is stunningly written, meticulously plotted, hallucinogenically realised and brutally honest. No one who reads it could doubt that Harrison might win the Booker if he could be bothered.

Light is also the book that novelist and critic Adam Roberts was so sure would win the Arthur C Clarke award, he offered to change his name to Adam Van Hoogenroberts if it didn't. We're still waiting . . .

Andrew Crumey

The Brick Moon by Edward Everett Hale (1870)

The term "science fiction" hadn't been invented in 1870, when the American magazine Atlantic Monthly published the first part of Edward Everett Hale's delightfully eccentric novella The Brick Moon. Readers lacked a ready-made pigeonhole for it, confronted by a fantasy about a group of visionaries who decide to make a 200-ft wide sphere of house-bricks, paint it white, and launch it into orbit.

Jules Verne's From the Earth to the Moon had appeared five years earlier, so Hale's work was not unprecendented, but while Verne chose to send his voyagers aloft using a giant cannon, Hale opts for the equally unfeasible but somehow more pleasing solution of a giant flywheel.

Hale gives technical details and calculations to support the plausibility of the venture. He even works out the total cost of the bricks ($60,000). There is an info-dump about latitude and longitude: the brick moon is designed to orbit from pole to pole so that people anywhere can determine their location by observing it. There are ruminations and speculations – and, to be honest, quite a few longeurs, even in a compass of only 25,000 words. But crucially there is humour. The brick moon gets launched accidentally with some people inside. Those left behind watch through telescopes as the travellers make their own little world, communicating by writing signs in big letters. They grow plants, hold church services, and their brick moon becomes a tiny, charming parody of Earth.

The Brick Moon did not appear in book form until 1899, when Hale was in his 70s, by which time HG Wells had appeared on the scene and Hale was slipping into obscurity. Nowadays he is little more than a footnote, remembered for having been the first to imagine artificial satellites. But what makes The Brick Moon still worth reading is not scientific vision, but sheer joyful quirkiness.

William Gibson

The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester (1957)

The idea of literary "favourites" makes me uneasy, but Alfred Bester's 1957 novel The Stars My Destination has remained very close to the top of my list for science fiction, since I first discovered it as a child (though I much prefer Bester's original title Tiger, Tiger, which was evidently deemed too arthouse for the trade). Bester was an urbane and successful Mad Av dandy, an anomaly among American SF writers of his day, and his best work is deliciously redolent of the brains and flash and bustle of postwar Manhattan. TSMD is a retelling of Dumas's The Count of Monte Cristo, its protagonist one Gully Foyle, lumpenprole untermensch turned revenging angel in a world utterly transformed by the discovery that teleportation is a natural and teachable human talent. Perfectly surefooted, elegantly pulpy, dizzying in its pace and sweep, TSMD is still as much fun as anything I've ever read. When I was lifting the literary equivalent of weights, in training for my own first novel, it was my talisman: evidence of how many different kinds of ass one quick narrative could kick. And that sheen of exuberant postwar modernism? They just aren't making any more of that.

Ursula K Le Guin

Virginia Woolf (1882–1941)

You can't write science fiction well if you haven't read it, though not all who try to write it know this. But nor can you write it well if you haven't read anything else. Genre is a rich dialect, in which you can say certain things in a particularly satisfying way, but if it gives up connection with the general literary language it becomes a jargon, meaningful only to an ingroup. Useful models may be found quite outside the genre. I learned a lot from reading the ever-subversive Virginia Woolf.

I was 17 when I read Orlando. It was half-revelation, half-confusion to me at that age, but one thing was clear: that she imagined a society vastly different from our own, an exotic world, and brought it dramatically alive. I'm thinking of the Elizabethan scenes, the winter when the Thames froze over. Reading, I was there, saw the bonfires blazing in the ice, felt the marvellous strangeness of that moment 500 years ago – the authentic thrill of being taken absolutely elsewhere.

How did she do it? By precise, specific descriptive details, not heaped up and not explained: a vivid, telling imagery, highly selected, encouraging the reader's imagination to fill out the picture and see it luminous, complete.

In Flush, Woolf gets inside a dog's mind, that is, a non-human brain, an alien mentality – very science-fictional if you look at it that way. Again what I learned was the power of accurate, vivid, highly selected detail. I imagine Woolf looking down at the dog asleep beside the ratty armchair she wrote in and thinking what are your dreams? and listening . . . sniffing the wind . . . after the rabbit, out on the hills, in the dog's timeless world.

Useful stuff, for those who like to see through eyes other than our own.

Russell Hoban

HP Lovecraft (1890–1937)

The main thing about HP Lovecraft is his too-muchness; he never uses three adjectives when five will do, but he writes words that haunt the memory: "In his house at R'lyeh dead Cthulhu waits dreaming." My recall of the multiplication table is shaky but those words disquiet me today as freshly as when I first read them.

Where did dead Cthulhu come from? Why did he rise up from the murky depths of Lovecraft's mental ocean? I say it's because there is a need for him and the rest of the maestro's monsters. Why is there such an appetite, such a hunger for scary stories and films? I think there is a primal horror in us. From where? From the Big Bang when Something came out of Nothing? From the nothingness we must become at life's end? I don't know, but I know it's there and we like to dress it up with a bolt through its neck or a black rubber alien suit; or as Cthulhu. Get a load of this: "A pulpy, tentacled head surmounted a grotesque and scaly body with rudimentary wings", with elements of "an octopus, a dragon, and a human caricature", "but it was the general outline of the whole that made it most shockingly frightful". Close your eyes and try to imagine this creature of non-Darwinian evolution. Just the look of this bozo is already a major horror, and we're not even into the story yet. While he's dead and dreaming in his house at R'lyeh ("Dun Foamin"?) his Cthulhuvibes are spreading worldwide and causing strange rites and observances here and there. Lovecraft is not everybody's mug of Ovaltine but I have always found him horribly cosy.

Liz Jensen

The Day of the Triffids by John Wyndham (1951)

As a teenager, one of my favourite haunts was Oxford's Botanical Gardens. I'd head straight for the vast heated greenhouses, where I'd pity my adolescent plight, chain-smoke, and glory in the insane vegetation that burgeoned there. The more rampant, brutally spiked, poisonous, or cruel to insects a plant was, the more it appealed to me. I'd shove my butts into their root systems. They could take it. My librarian mother disapproved mightily of the fags but when under interrogation I confessed where I'd been hanging out – hardly Sodom and Gomorrah – she spotted a literary opportunity, and slid John Wyndham's The Day of the Triffids my way. I read it in one sitting, fizzing with the excitement of recognition. I knew the triffids already: I'd spent long hours in the jungle with them, exchanging gases. Wyndham loved to address the question that triggers every invented world: the great "What if . . ." What if a carnivorous, travelling, communicating, poison-spitting oil-rich plant, harvested in Britain as biofuel, broke loose after a mysterious "comet-shower" blinded most of the population? That's the scenario faced by triffid-expert Bill Masen, who finds himself a sighted man in a sightless nation. Cataclysmic change established, cue a magnificent chain reaction of experimental science, physical and political crisis, moral dilemmas, new hierarchies, and hints of a new world order. Although the repercussions of an unprecedented crisis and Masen's personal journey through the new wilderness form the backbone of the story, it's the triffids that root themselves most firmly in the reader's memory. Wyndham described them botanically, but he left enough room for the reader's imagination to take over. The result being that everyone who reads The Day of the Triffids creates, in their mind's eye, their own version of fiction's most iconic plant. Mine germinated in an Oxford greenhouse, in a cloud of cigarette smoke.

Hari Kunzru

Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (1972)