On Love

+4

blue moon

senorita

tatiana

eddie

8 posters

Page 1 of 2

Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

On Love

On Love

All About Love: Anatomy of an Unruly Emotion by Lisa Appignanesi – review

An ambitious dissection of the most intangible human emotion turns to literature and Freud to chart the experience in all its forms

Salley Vickers The Observer, Sunday 24 April 2011

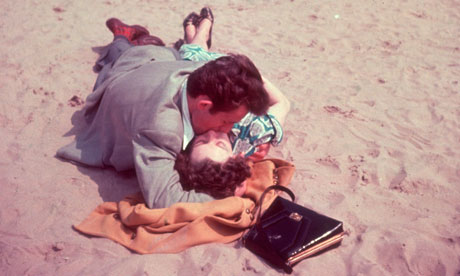

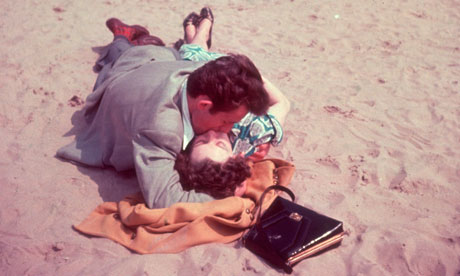

Love: 'resistant to analysis because its existence is predicated on experience'. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Lisa Appignanesi is an ambitious writer who is temperamentally drawn to big subjects. Her previous book, Mad, Bad and Sad, explored the disturbing history of the plight of women whose mental state did not conform to contemporary notions of "health". Her memoir, Losing the Dead, was a compelling account of her own family history, in which loss, memory and desire played haunting roles. Now, in All About Love, she has turned her attention to the subject where most of us locate our beginnings, which none of us escape and which at some point in our lives will generally threaten to take us over, like a madness.

All About Love: Anatomy of an Unruly Emotion by Lisa Appignanesi

Appignanesi is refreshingly candid about what she is not going to be dealing with. She elects to concentrate on the culture of the western world, while acknowledging the influence of the east; she chooses not to "single out homosexuality", although she includes homosexual accounts of loving in her research; and she avoids the more sensational reaches of "love" – sadism, masochism and necrophilia – feeling that living in times where excess is "rampant in the media", a rebalancing focus on "ordinary love" is extraordinary enough. But this, of course, poses the really vexed question. What on earth is "ordinary love"?

Feste, one of Shakespeare's shrewd fools, offers a characteristically misty answer to this question. "Tis not hereafter…" he sings, by which he means not just that love is of the moment, but that it is easier to suggest what love is not than what it is. It is not, for instance, as Appignanesi points out, a matter of changes to the neural synapses or the lighting up of critical areas in the brain. That all emotional states have a physical corollary is not news; we are psychosomatic creatures whose minds and bodies are in cahoots.

What emerges from the book's attempt to chart the "arc of love" is that, like time, God and happiness, this is a subject resistant to analysis, because its existence is predicated on experience. It is possible, sometimes, to say what time, belief in God or being in love do to us; but this gives no real clue to what these words stand for. "What is your substance, whereof are you made?" as Shakespeare asks elsewhere, and does not stay for an answer.

Nonetheless, Appignanesi has a stab at providing an answer. Her account – which moves from first love to married love, to adultery, families and friendship – is enlivened with personal anecdotes; this is the yeast that leavens the dough of information. Her references are wide-ranging and eclectic – from the ancients to Oprah – mirroring the mish-mash of attitudes that love provokes. Significantly, much of her material derives from poets and novelists, on the basis that reality is often more accurately conveyed in fiction than via reported "fact", whether scientific data or personal record. What we "make up" as fiction is less likely to be tainted by the usual human defences against self-revelation and self-knowledge. As Oscar Wilde knew, "The truest fiction is the most feigning".

Appignanesi is particularly strong on the Russians: Turgenev and Tolstoy are key witnesses on the delusion of "first" love (she quotes from Turgenev's deeply intelligent story "First Love": "I had no first love... I began with the second") and the emotional economy of love triangles. Appignanesi has co-authored a book on Freud, and the influence of psychoanalysis underwrites her account of both these states. The ecstasy of first love recapitulates the oceanic feelings of the infant at the breast, and its perennial anguish derives from the anticipation of an inevitable second banishment, which mirrors the childhood expulsion from that Eden. The adulterous triangle is, unsurprisingly, the natural offspring of the Oedipal triad. But she also gives a valuable account of the role of love in the development of Freud's theory of analysis, which was, at heart, Romantic. Freud was much impressed by Wilhelm Jensen's novella Gravdia, from which he derived his idea of love as a catalyst of self-knowledge capable of unblocking psychosexual resistance. Appignanesi quotes Freud: "Every psychoanalytic treatment is an attempt at liberating repressed love which has found a meagre outlet in the compromise of a symptom." More urgently he wrote: "In the last resort we must begin to love in order not to fall ill, and we are bound to fall ill if… we are unable to love."

Understandably, much of the book is about love's shady cousin, sex. For one thing, sex is more tangible as a subject, more amenable to documentation and statistics, and therefore, one senses, Appignanesi falls back upon the sexual with some relief. But the conclusions she draws are somewhat depressing. By her account, the split between sex and emotion in modern youth, fuelled by increased drug use, is growing wider. On the other hand (or, more accurately, by the same token), there is the new enthusiasm for the cult of celibacy. I'm sceptical about these so-called "modern" phenomena. Stendhal, whom Appignanesi quotes, gives a pretty clear-headed account of that psyche/sexual split, as does Tolstoy, who, after a life of erotic abandonment, in his later years fanatically cultivated celibacy.

Perhaps because, as she herself has acknowledged, love of her children is the love story Appignanesi is now most stirred by, the most successful section of the book is on love in families. She quotes the Earl of Rochester – "Before I got married I had six theories about bringing up children; now I have six children and no theorie" – and something of the earl's agreeable pragmatism informs her thought. She is tender, without being sentimental, about the passionate attachments babies evoke, as well as need. But she is also good on hate, that vital feature of family life often brushed under the carpet. (Freud never discussed the fact that it is Jocasta's attempt to murder her son that leads to his incestuous union with her.)

Friendship completes the arc of the book and Appignanesi again comments on the contemporary ethos that makes her want to conclude on a temperate note. "It is unromantic civility and quotidian generosity that encourage our intimacies to endure." Undeniably true. But the life of the book lies is its author's apprehension that temperance is, alas, not what we crave. Love, for all its pains – or because of its pains – offers a promise of meaning, no matter that the nature of this "meaning" is forever deferred. Appignanesi quotes the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips's observation that our desire is always in excess of the object's capacity to satisfy it. There is a sense in which the worldly wise Feste is wrong: love is "hereafter", because its meaning lies precisely in the excitement of a promise that never loses its tarnish by being fulfilled.

Salley Vickers's collection of stories, Aphrodite's Hat, is published by Fourth Estate

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

An ambitious dissection of the most intangible human emotion turns to literature and Freud to chart the experience in all its forms

Salley Vickers The Observer, Sunday 24 April 2011

Love: 'resistant to analysis because its existence is predicated on experience'. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Lisa Appignanesi is an ambitious writer who is temperamentally drawn to big subjects. Her previous book, Mad, Bad and Sad, explored the disturbing history of the plight of women whose mental state did not conform to contemporary notions of "health". Her memoir, Losing the Dead, was a compelling account of her own family history, in which loss, memory and desire played haunting roles. Now, in All About Love, she has turned her attention to the subject where most of us locate our beginnings, which none of us escape and which at some point in our lives will generally threaten to take us over, like a madness.

All About Love: Anatomy of an Unruly Emotion by Lisa Appignanesi

Appignanesi is refreshingly candid about what she is not going to be dealing with. She elects to concentrate on the culture of the western world, while acknowledging the influence of the east; she chooses not to "single out homosexuality", although she includes homosexual accounts of loving in her research; and she avoids the more sensational reaches of "love" – sadism, masochism and necrophilia – feeling that living in times where excess is "rampant in the media", a rebalancing focus on "ordinary love" is extraordinary enough. But this, of course, poses the really vexed question. What on earth is "ordinary love"?

Feste, one of Shakespeare's shrewd fools, offers a characteristically misty answer to this question. "Tis not hereafter…" he sings, by which he means not just that love is of the moment, but that it is easier to suggest what love is not than what it is. It is not, for instance, as Appignanesi points out, a matter of changes to the neural synapses or the lighting up of critical areas in the brain. That all emotional states have a physical corollary is not news; we are psychosomatic creatures whose minds and bodies are in cahoots.

What emerges from the book's attempt to chart the "arc of love" is that, like time, God and happiness, this is a subject resistant to analysis, because its existence is predicated on experience. It is possible, sometimes, to say what time, belief in God or being in love do to us; but this gives no real clue to what these words stand for. "What is your substance, whereof are you made?" as Shakespeare asks elsewhere, and does not stay for an answer.

Nonetheless, Appignanesi has a stab at providing an answer. Her account – which moves from first love to married love, to adultery, families and friendship – is enlivened with personal anecdotes; this is the yeast that leavens the dough of information. Her references are wide-ranging and eclectic – from the ancients to Oprah – mirroring the mish-mash of attitudes that love provokes. Significantly, much of her material derives from poets and novelists, on the basis that reality is often more accurately conveyed in fiction than via reported "fact", whether scientific data or personal record. What we "make up" as fiction is less likely to be tainted by the usual human defences against self-revelation and self-knowledge. As Oscar Wilde knew, "The truest fiction is the most feigning".

Appignanesi is particularly strong on the Russians: Turgenev and Tolstoy are key witnesses on the delusion of "first" love (she quotes from Turgenev's deeply intelligent story "First Love": "I had no first love... I began with the second") and the emotional economy of love triangles. Appignanesi has co-authored a book on Freud, and the influence of psychoanalysis underwrites her account of both these states. The ecstasy of first love recapitulates the oceanic feelings of the infant at the breast, and its perennial anguish derives from the anticipation of an inevitable second banishment, which mirrors the childhood expulsion from that Eden. The adulterous triangle is, unsurprisingly, the natural offspring of the Oedipal triad. But she also gives a valuable account of the role of love in the development of Freud's theory of analysis, which was, at heart, Romantic. Freud was much impressed by Wilhelm Jensen's novella Gravdia, from which he derived his idea of love as a catalyst of self-knowledge capable of unblocking psychosexual resistance. Appignanesi quotes Freud: "Every psychoanalytic treatment is an attempt at liberating repressed love which has found a meagre outlet in the compromise of a symptom." More urgently he wrote: "In the last resort we must begin to love in order not to fall ill, and we are bound to fall ill if… we are unable to love."

Understandably, much of the book is about love's shady cousin, sex. For one thing, sex is more tangible as a subject, more amenable to documentation and statistics, and therefore, one senses, Appignanesi falls back upon the sexual with some relief. But the conclusions she draws are somewhat depressing. By her account, the split between sex and emotion in modern youth, fuelled by increased drug use, is growing wider. On the other hand (or, more accurately, by the same token), there is the new enthusiasm for the cult of celibacy. I'm sceptical about these so-called "modern" phenomena. Stendhal, whom Appignanesi quotes, gives a pretty clear-headed account of that psyche/sexual split, as does Tolstoy, who, after a life of erotic abandonment, in his later years fanatically cultivated celibacy.

Perhaps because, as she herself has acknowledged, love of her children is the love story Appignanesi is now most stirred by, the most successful section of the book is on love in families. She quotes the Earl of Rochester – "Before I got married I had six theories about bringing up children; now I have six children and no theorie" – and something of the earl's agreeable pragmatism informs her thought. She is tender, without being sentimental, about the passionate attachments babies evoke, as well as need. But she is also good on hate, that vital feature of family life often brushed under the carpet. (Freud never discussed the fact that it is Jocasta's attempt to murder her son that leads to his incestuous union with her.)

Friendship completes the arc of the book and Appignanesi again comments on the contemporary ethos that makes her want to conclude on a temperate note. "It is unromantic civility and quotidian generosity that encourage our intimacies to endure." Undeniably true. But the life of the book lies is its author's apprehension that temperance is, alas, not what we crave. Love, for all its pains – or because of its pains – offers a promise of meaning, no matter that the nature of this "meaning" is forever deferred. Appignanesi quotes the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips's observation that our desire is always in excess of the object's capacity to satisfy it. There is a sense in which the worldly wise Feste is wrong: love is "hereafter", because its meaning lies precisely in the excitement of a promise that never loses its tarnish by being fulfilled.

Salley Vickers's collection of stories, Aphrodite's Hat, is published by Fourth Estate

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: On Love

Re: On Love

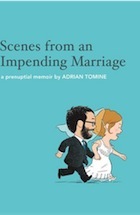

Scenes from an Impending Marriage by Adrian Tomine – review

Cartoonist Adrian Tomine's 'prenuptial memoir' lays bare the fiasco of the modern wedding with acid wit

Rachel Cooke The Observer, Sunday 1 May 2011

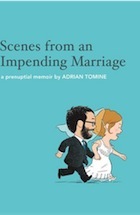

Scenes from an Impending Marriage by Adrian Tomine.

Do you have a friend who is in the process of turning into Bridezilla (or even Groomzilla, since women certainly don't have a monopoly on wedding madness)? Then I have the perfect gift for her – though on second thoughts, perhaps this is a treat best left until after her nuptials when, one hopes, your friend will miraculously recover her mislaid sense of humour. Adrian Tomine, author of the brilliant Shortcomings and a cartoonist at the New Yorker, has written a "prenuptial memoir" called Scenes from an Impending Marriage in which he lays bare, with ruthless efficiency, the bizarre effect that organising a wedding can have on even the sane and the cynical (and Tomine, as fans will know, is nothing if not cynical). Is it accurate? Yes, as a laser. Is it hilarious? All I can say is that it will make you – if not your good pal Bridezilla – snort like a dragon. Don't, on any account, combine reading it with lunch.

Scenes from an Impending Marriage: a prenuptial memoir by Adrian Tomine

Tomine's specialist subject is angst and alienation among young bohemians; his characters wear heavy spectacles and cool sneakers, they eat a lot of takeout, and they worry excessively about fitting in. It's a world he knows well: Tomine has never flinched from the idea that much of what he writes and draws is thinly disguised autobiography. But because he's so devastatingly observant, he cannot be anything other than hardest on himself. Scenes from an Impending Marriage is more of the same, really, only this time it's explicit: the book began its life when his fiancee, Sarah, begged him to draw a miniature comic book for their guests as a wedding "favour". I wonder what those guests think now. One of the book's funniest sections is about who one invites to a wedding, and why. His list, compared with hers, is tiny. "Come on!" he yells, in a funk before they've even begun. "We've gotta break this endless cycle of obligation and reciprocity!"

It's all here: from choosing a venue, to picking a DJ, to registering for a wedding list ("It's emblematic of our whole culture: 'I want lots of stuff and I want to shoot a gun!'" observes Adrian in Crate & Barrel, where couples must use a barcode scanner to compile their list). There is even a section entitled: "An Even-Handed Acknowledgment of Both Families' Cultural Heritage", whose moral is that taiko drummers (Tomine has Japanese roots) and bagpipe players do not, under any circumstances, mix. The blurb on the back of Faber's British edition remarks that the book is replete with "unabashed tenderness" – which is sweet, but not entirely true. I counted just one lovey-dovey frame in the entire book. Even the moment when, late on their wedding night, the happy couple wind up companionably eating greasy burgers in their hotel is shot through with futility. At the wedding, they failed to eat anything at all; in the end, they passed through the fruits of all their labours as if in a crazy dream.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Cartoonist Adrian Tomine's 'prenuptial memoir' lays bare the fiasco of the modern wedding with acid wit

Rachel Cooke The Observer, Sunday 1 May 2011

Scenes from an Impending Marriage by Adrian Tomine.

Do you have a friend who is in the process of turning into Bridezilla (or even Groomzilla, since women certainly don't have a monopoly on wedding madness)? Then I have the perfect gift for her – though on second thoughts, perhaps this is a treat best left until after her nuptials when, one hopes, your friend will miraculously recover her mislaid sense of humour. Adrian Tomine, author of the brilliant Shortcomings and a cartoonist at the New Yorker, has written a "prenuptial memoir" called Scenes from an Impending Marriage in which he lays bare, with ruthless efficiency, the bizarre effect that organising a wedding can have on even the sane and the cynical (and Tomine, as fans will know, is nothing if not cynical). Is it accurate? Yes, as a laser. Is it hilarious? All I can say is that it will make you – if not your good pal Bridezilla – snort like a dragon. Don't, on any account, combine reading it with lunch.

Scenes from an Impending Marriage: a prenuptial memoir by Adrian Tomine

Tomine's specialist subject is angst and alienation among young bohemians; his characters wear heavy spectacles and cool sneakers, they eat a lot of takeout, and they worry excessively about fitting in. It's a world he knows well: Tomine has never flinched from the idea that much of what he writes and draws is thinly disguised autobiography. But because he's so devastatingly observant, he cannot be anything other than hardest on himself. Scenes from an Impending Marriage is more of the same, really, only this time it's explicit: the book began its life when his fiancee, Sarah, begged him to draw a miniature comic book for their guests as a wedding "favour". I wonder what those guests think now. One of the book's funniest sections is about who one invites to a wedding, and why. His list, compared with hers, is tiny. "Come on!" he yells, in a funk before they've even begun. "We've gotta break this endless cycle of obligation and reciprocity!"

It's all here: from choosing a venue, to picking a DJ, to registering for a wedding list ("It's emblematic of our whole culture: 'I want lots of stuff and I want to shoot a gun!'" observes Adrian in Crate & Barrel, where couples must use a barcode scanner to compile their list). There is even a section entitled: "An Even-Handed Acknowledgment of Both Families' Cultural Heritage", whose moral is that taiko drummers (Tomine has Japanese roots) and bagpipe players do not, under any circumstances, mix. The blurb on the back of Faber's British edition remarks that the book is replete with "unabashed tenderness" – which is sweet, but not entirely true. I counted just one lovey-dovey frame in the entire book. Even the moment when, late on their wedding night, the happy couple wind up companionably eating greasy burgers in their hotel is shot through with futility. At the wedding, they failed to eat anything at all; in the end, they passed through the fruits of all their labours as if in a crazy dream.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: On Love

Re: On Love

Venus Frigida: Rubens's portrait of love in a cold climate

Throughout the month of December, Jonathan Jones is picking his favourite wintry artworks. Today, he shivers in sympathy with Rubens's nude Mediterranean goddess, who finds herself far from home in the inhospitable north

guardian.co.uk, Friday 16 December 2011 10.52 GMT

Venus is a Mediterranean goddess. Her enchanted home is the isle of Cyprus. In Botticelli’s painting The Birth of Venus she skims over the warm green sea on a shell. This classical deity personifies not only Love, but Love in a warm climate, with grapes, wine and nudity. So what happens when she travels north? Rubens portrays her shivering with cold in a glowering landscape, her nudity exposed to the wintry north. His painting illustrates a classical adage that says: ‘Without Bacchus and Ceres, Venus freezes.’ Love in winter, in other words, needs good food, good booze and a cosy bedroom

Photograph: Hugo Maertens/Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

Throughout the month of December, Jonathan Jones is picking his favourite wintry artworks. Today, he shivers in sympathy with Rubens's nude Mediterranean goddess, who finds herself far from home in the inhospitable north

guardian.co.uk, Friday 16 December 2011 10.52 GMT

Venus is a Mediterranean goddess. Her enchanted home is the isle of Cyprus. In Botticelli’s painting The Birth of Venus she skims over the warm green sea on a shell. This classical deity personifies not only Love, but Love in a warm climate, with grapes, wine and nudity. So what happens when she travels north? Rubens portrays her shivering with cold in a glowering landscape, her nudity exposed to the wintry north. His painting illustrates a classical adage that says: ‘Without Bacchus and Ceres, Venus freezes.’ Love in winter, in other words, needs good food, good booze and a cosy bedroom

Photograph: Hugo Maertens/Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Antwerp

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: On Love

Re: On Love

The first sexual revolution: lust and liberty in the 18th century

Adulterers and prostitutes could be executed and women were agreed to be more libidinous than men – then in the 18th century attitudes to sex underwent an extraordinary change

Faramerz Dabhoiwala

guardian.co.uk, Friday 20 January 2012 22.55 GMT

The rise of sexual freedom … detail from The Bed, etching, engraving and drypoint by Rembrandt (1646). Photograph: © Trustees of the British Museum

We believe in sexual freedom. We take it for granted that consenting men and women have the right to do what they like with their bodies. Sex is everywhere in our culture. We love to think and talk about it; we devour news about celebrities' affairs; we produce and consume pornography on an unprecedented scale. We think it wrong that in other cultures its discussion is censured, people suffer for their sexual orientation, women are treated as second-class citizens, or adulterers are put to death.

The Origins of Sex: A History of the First Sexual Revolution

by Faramerz Dabhoiwala

Yet a few centuries ago, our own society was like this too. In the 1600s people were still being executed for adultery in England, Scotland and north America, and across Europe. Everywhere in the west, sex outside marriage was illegal, and the church, the state and ordinary people devoted huge efforts to hunting it down and punishing it. This was a central feature of Christian society, one that had grown steadily in importance since late antiquity. So how and when did our culture change so strikingly? Where does our current outlook come from? The answers lie in one of the great untold stories about the creation of our modern condition.

When I stumbled on the subject, more than a decade ago, I could not believe that such a huge transformation had not been properly understood. But the more I pursued it, the more amazing material I uncovered: the first sexual revolution can be traced in some of the greatest works of literature, art and philosophy ever produced – the novels of Henry Fielding and Jane Austen, the pictures of Reynolds and Hogarth, the writings of Adam Smith, David Hume and John Stuart Mill. And it was played out in the lives of tens of thousands of ordinary men and women, otherwise unnoticed by history, whose trials and punishments for illicit sex are preserved in unpublished judicial records. Most startling of all were my discoveries of private writings, such as the diary of the randy Dutch embassy clerk Lodewijk van der Saan, posted to London in the 1690s; the emotional letters sent to newspapers by countless hopeful and disappointed lovers; and the piles of manuscripts about sexual freedom composed by the great philosopher Jeremy Bentham but left unpublished, to this day, by his literary executors. Once noticed, the effects of this revolution in attitudes and behaviour can be seen everywhere when looking at the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. It was one of the key shifts from the pre-modern to the modern world.

❦

Since the dawn of history, every civilisation had punished sexual immorality. The law codes of the Anglo-Saxon kings of England treated women as chattels, but they also forbade married men to fornicate with their slaves, and ordered that adulteresses be publicly disgraced, lose their goods and have their ears and noses cut off. Such severity reflected the Christian church's view of sex as a dangerously polluting force, as well as the patriarchal commonplace that women were more lustful than men and liable to lead them astray. By the later middle ages, it was common in places such as London, Bristol and Gloucester for convicted prostitutes, bawds, fornicators and adulterers to be subjected to elaborate ritual punishments: to have their hair shaved off or to be dressed in especially degrading outfits, severely whipped, displayed in a pillory or public cage, paraded around for public humiliation and expelled for ever from the community.

The reformation brought a further hardening of attitudes. The most fervent Protestants campaigned vigorously to reinstate the biblical death penalty for adultery and other sexual crimes. Wherever Puritan fundamentalists gained power, they pursued this goal – in Geneva and Bohemia, in Scotland, in the colonies of New England and in England itself. After the Puritans had led the parliamentary side to victory in the English civil war, executed the King and abolished the monarchy, they passed the Adultery Act of 1650. Henceforth, adulterers and incorrigible fornicators and brothel-keepers were simply to be executed, as sodomites and bigamists already were.

Of course, sexual discipline was never perfect. Men and women constantly gave way to temptation – and then had to be flogged, imprisoned, fined and shamed to reform them. Many others, especially the wealthy and powerful, escaped punishment. As was the case with other crimes, the full rigour of the law was never uniformly or consistently applied. All the same, sexual discipline was a central facet of pre-modern western society, and its unceasing promotion had a profound effect on ordinary men and women. Most people internalised its principles deeply and participated in the disciplining of others. There was no coherent philosophy of sexual liberty, no way of conceiving of a society without moral policing. It seemed obvious that illicit sex had to be combated because it angered God, prevented salvation, damaged personal relations and undermined social order. Sex was emphatically not a private affair.

So pervasive was this ideology that even those who paid with their lives for defying it could not escape its hold over their minds and actions. When the Massachusetts settler James Britton fell ill in the winter of 1644, he became gripped by a "fearful horror of conscience" that this was God's punishment on him for his past sins. So he publicly confessed that once, after a night of heavy drinking, he had tried (but failed) to have sex with a young bride, Mary Latham. Though she now lived far away, in Plymouth colony, the magistrates there were alerted. She was found, arrested and brought back, across the icy landscape, to stand trial in Boston. When, despite her denial that they had actually had sex, she was convicted of adultery, she broke down, confessed it was true, "proved very penitent, and had deep apprehension of the foulness of her sin … and was willing to die in satisfaction to justice". On 21 March, a fortnight after her sentence, she was taken to the public scaffold. Britton was executed alongside her; he, too, "died very penitently". In the shadow of the gallows, Latham addressed the assembled crowds, exhorting other young women to be warned by her example, and again proclaiming her abhorrence and penitence for her terrible crime against God and society. Then she was hanged. She was 18 years old.

❦

That is the world we have left behind. Over the following century and a half it was transformed by a great revolution that laid the ground for the sexual culture of the 19th and 20th centuries, and of our own day.

The most obvious change was a surge in pre- and extramarital sex. We can measure this, crudely but unmistakably, in the numbers of children conceived out of wedlock. During the 17th century this figure had been extremely low: in 1650 only about 1% of all births in England were illegitimate. But by 1800, almost 40% of brides came to the altar pregnant, and about a quarter of all first-born children were illegitimate. It was to be a permanent change in behaviour.

Just as striking was the collapse of public punishment, which made this new sexual freedom possible. By 1800, most forms of consensual sex between men and women had come to be treated as private, beyond the reach of the law. This extraordinary reversal of centuries of severity was partly the result of increasing social pressures. The traditional methods of moral policing had evolved in small, slow, rural communities in which conformity was easy to enforce. Things were different in towns, especially in London. At the end of the middle ages only about 40,000 people lived there, but by 1660 there were already 400,000; by 1800 there would be more than a million, and by 1850 most of the British population lived in towns. This extraordinary explosion created new kinds of social pressures and new ways of living, and placed the conventional machinery of sexual discipline under growing strain.

Urban living provided many more opportunities for sexual adventure. It also gave rise to new, professional systems of policing, which prioritised public order. Crime became distinguished from sin. And the fast circulation of news and ideas created a different, freer and more pluralist intellectual environment.

This was crucial to the development of the ideal of sexual freedom. By the later 18th century, for the first time, many serious observers had come to take it for granted that sex was a private matter, that men and women should be free to indulge in it irrespective of marriage, and that sexual pleasure should be celebrated as one of the purposes of life. As well as reinterpreting the Bible, they found support in new ideas about the importance of personal conscience and in the laws of nature, which were regarded as more clearly indicative of God's will than the inherited dogma of the church and the text of the scriptures. In his 1730 work, Christianity as Old as the Creation, the Oxford don Matthew Tindal ridiculed traditional sexual norms as priestly inventions, no more appropriate to a modern state than the biblical prohibitions against drinking blood or lending money: "Enjoying a woman, or lusting after her, can't be said, without considering the circumstances, to be either good or evil. That warm desire, which is implanted in human nature, can't be criminal, when perused after such a manner as tends most to promote the happiness of the parties, and to propagate and preserve the species."

In a similar vein, the Rev Robert Wallace, one of the leaders of the Church of Scotland in the mid-18th century, wrote a treatise seriously commending "a much more free commerce of the sexes". By that he meant complete liberty for people to cohabit successively with as many partners as they liked – "A woman's being enjoyed by a dozen … can never render her less fit or agreeable to a 13th". As John Wilkes's 1754 Essay on Woman put it: "Life can little more supply / Than just a few good Fucks, and then we die."

❦

It's no accident that all these early celebrations of the new sexual world were voiced by white, upper-class men. In practice, sexual liberty was limited in important ways. The bastardy laws continued to apply to the labouring classes: their morals remained a public matter. The new permissiveness towards "natural" freedoms also led to a sharper definition and abhorrence of supposedly "unnatural" behaviour. Homosexual acts in particular came to be persecuted with increasing violence: throughout the 18th century there were regular executions for sodomy. Even after 1830, when hanging for the offence was ended, thousands of men were publicly humiliated in the pillory, or sentenced to jail, for their unnatural perversions – Oscar Wilde's imprisonment with hard labour for two years in 1895 is only the best-known example.

Yet the general advance of sexual freedom and the expansion of urban life also fostered the development of an increasingly assertive homosexual sub-culture. Some of the most remarkable utterances of the 18th century were the first principled defences of same-sex behaviour as natural, universal and harmless. One night in 1726, William Brown, a married man, was arrested at a notorious pick-up spot with another man's hand in his breeches. When surrounded by hostile watchmen and challenged as to "why he took such indecent liberties … he was not ashamed to answer, 'I did it because I thought I knew him, and I think there is no crime in making what use I please of my own body'". That sodomy had been accepted by all the greatest civilisations of the world was one of the themes of the young clergyman Thomas Cannon's Ancient and Modern Pederasty (1749). "Every dabbler knows by his classics," he pointed out, "that boy-love ever was the top refinement of most enlightened ages." Arguments of the same kind were developed systematically by the Yorkshire gentlewoman Anne Lister (1791-1840), who set down in her diaries the first full justification of lesbian love in English, and by Bentham, the most influential reformer of the age, who defended the rights of homosexuals in countless private discussions and over many hundreds of pages of notes and treatises.

Attitudes towards women's sexuality underwent similarly dramatic shifts. The idea that sexual freedom was as natural and desirable for women as for men was born in the 18th century. By the early 19th century, many feminists, socialists and other progressive thinkers on both sides of the Atlantic decried marriage and advocated free love as a means to the emancipation of women and the creation of a more just society. Among those who held such views were Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor, Robert Owen and many Owenites, and Percy Bysshe Shelley. In the long term, this egalitarian way of thinking was to provide the intellectual foundation for women's sexual liberation more generally.

Yet more immediately the rise of sexual freedom had a much more ambiguous legacy. Women who were rich or powerful enough to escape social ostracism could take advantage of it: many female aristocrats had notoriously open marriages. But on the whole female lust now came to be ever more strongly stigmatised as "unnatural", for it threatened the basic principle that (as one of William III's bishops had put it) "Men have a property in their wives and daughters" and therefore owned their bodies too. Thus, at the same time as it was increasingly argued that sexual liberty was natural for men, renewed stress was placed, often in the same breath, on the necessity of chastity in respectable women.

The effects of this sharpened double standard can be seen everywhere in 18th-, 19th- and 20th-century culture. James Boswell's diary records the tragic story of Jean, the brilliant only daughter of Henry Home, Lord Kames, one of the leading thinkers of the Enlightenment. In the early 1760s, when she was only 16 or 17 and already married, she embarked on a passionate affair with Boswell, arguing to him that they were doing nothing wrong:

"She was a subtle philosopher. She said, 'I love my husband as a husband, and you as a lover, each in his own sphere. I perform for him all the duties of a good wife. With you, I give myself up to delicious pleasures. We keep our secret. Nature has so made me that I shall never bear children. No one suffers because of our loves. My conscience does not reproach me, and I am sure that God cannot be offended by them.'"

A decade later, when her husband divorced her over another affair, she declared "that she hoped that God Almighty would not punish her for the only crime she could charge herself with, which was the gratification of those passions which he himself had implanted in her nature." But her father, the scholar and moral authority, took the conventional view that adultery in a man "may happen occasionally, with little or no alienation of affection", but in a woman was unpardonable. After his daughter's divorce, he and Lady Kames exiled her to France and never saw her again.

❦

Indeed, the first sexual revolution was characterised by an extraordinary reversal in assumptions about female sexuality. Ever since the dawn of western civilisation it had been presumed that women were the more lustful sex. As they were mentally, morally and physically weaker than males, it followed that they were less able to control their passions and thus (like Eve) more likely to tempt others into sin. Yet, by 1800, exactly the opposite idea had become entrenched. Now it was believed that men were much more naturally libidinous and liable to seduce women. Women had come to be seen as comparatively delicate and sexually defensive, needing to be constantly on their guard against male rapacity. The notion of women's relative sexual passivity became fundamental to sexual dynamics across the western world. Its effects were ubiquitous – they still are.

A crucial reason was the rise of women as public writers, which introduced into the cultural mainstream powerful new female perspectives on courtship and lust. This was an unprecedented development. In all earlier times, women's direct intervention in public discussion had been very limited. Men monopolised every medium in which male and female qualities were prescribed and reinforced – fiction, drama, poetry, sermons, journalism and so on. But from the later 17th century onwards, women emerged for the first time as a permanent part of the world of letters. As playwrights, poets, novelists and philosophers, women influenced male authors, looked to one another, and addressed themselves directly to the public. And in much female writing about sexual relations, the bottom line was, as the teenage poet Sarah Fyge explained in 1686, that men were always trying "to make a prey" of chaste women. Male bluster about female lust was but to make women "the scapegoat" – it was men who constantly pressured and ensnared women, who were insatiable in their thirst for new conquests, and shameless in their commission. As the feminist Mary Astell put it bitterly in 1700, "'Tis no great matter to them if women, who were born to be their slaves, be now and then ruined for their entertainment". No woman could ever "be too much upon her guard".

None of these ideas was entirely new, but it was only from around 1700 that they came to be put forward publicly, in a way that discernibly changed the culture of the age. Especially influential in the long term was the role of women in creating the new genre of the novel, which by the middle of the 18th century had become the most influential fictional form and become a central conduit of moral and social education. Samuel Johnson noted in 1750 that women's breaking of the male monopoly on writing, and their "stronger arguments", had overturned the ancient masculine falsehood that women were the more fickle and lecherous sex.

All this explains why the first major novelists of the English language were so obsessed with seduction. Samuel Richardson, whose Pamela, Clarissa and Sir Charles Grandison were the most sensationally popular and influential pieces of fiction of the 18th century, was a classic instance of the growing power of female viewpoints. For all its originality, the general approach and subject matter of his fiction owes an obvious debt to the stream of earlier novels about heroines courted, seduced, raped and oppressed, which had flowed from the pens of pioneering female writers such as Penelope Aubin, Jane Barker, Mary Davys, Eliza Haywood and Elizabeth Rowe. A wide circle of women acquaintances, readers and correspondents helped him; in turn, his work presented eyewitness perspectives of respectable women under threat from rapacious superior men. Right through the 19th century, it is hard to think of many serious novelists who did not pursue the seduction narrative.

❦

Equally important to modern ways of thinking was the increasing sexualisation of race and class. The presumption that lower-class and non-white women were less sexually restrained became a matter of both investigation and titillation. As sexual norms were increasingly held to vary according to race, class and sex, so the transgression of such boundaries (in reality and in fantasy) became ever more erotically charged. This was the origin of the great British obsession with sex and class, which equally affected homosexual passion. "We don't like people like ourselves," explains a middle-class character in one 1950s novel about gay lust. "We don't want anybody who shares our standards. In fact, we want the very opposite. We want the primitive, the uneducated, the tough." Even some of the most basic features of our sexual desire are therefore not natural and unchanging, but historically created. What we think of as "natural" in men and women, where the boundaries lie between the normal and the deviant, how we feel about the pursuit of pleasure and the transgression of sexual norms – all these are matters on which our current attitudes are fundamentally different from those that have prevailed for most of western history.

The new fascination with class and licentiousness helped to transform attitudes towards prostitution. The conventional view had been that prostitutes were the worst reprobates of all, deserving of the harshest punishments. But from the middle of the 18th century this perspective was matched, and often overshadowed, by the presumption that prostitutes themselves were ultimately the innocent victims of male lust and social deprivation. Vast efforts were poured into the foundation of asylums, workhouses and other charities for fallen women and girls at risk of seduction. Many contemporaries saw obvious parallels between black and white slavery. "What are the sorrows of the enslaved negro from which the outcast prostitute of London is exempted?" asked one late-Georgian activist. "A seducer or ravisher has torn them both, for ever, from the abodes of their youth … Is the bosom of the unhappy girl less tender than that of the swarthy savage?"

The rescue of fallen women, and the abolition of "white slavery", consequently became a craze to which some of the most prominent figures in public life devoted great energy. At the height of his fame, Charles Dickens threw himself into the foundation of a refuge for penitents, with the financial backing of the millionairess Angela Burdett-Coutts. His fellow novelist George Gissing tried (and failed) to redeem a young prostitute by marrying her himself. William Gladstone called the issue "the chief burden of my soul", and for decades, even while prime minister, roamed the streets at night attempting to save prostitutes.

❦

The final notable feature of the first sexual revolution was the birth of a new kind of media culture, in which private affairs and personal opinions were given unprecedented publicity. The explosion of publishing created a much more democratic and permanent network of public communication than had ever existed before. The mass proliferation of newspapers and magazines, and a new-found fascination with the boundaries of the private and the public, combined to produce the first age of sexual celebrity. The sayings and doings of famous courtesans now came to be routinely analysed in print, and their portraits were endlessly painted, engraved and caricatured. Many of them skilfully promoted themselves, keeping their names and faces in the public eye by publishing memoirs and publicising their image. By the middle of the 18th century, a visitor to any of London's print shops could have bought dozens of different portraits, in all shapes and sizes, of Kitty Fisher, Fanny Murray, Nancy Dawson and every other well-known lady of pleasure. Cheapest of all were tiny prints made to fit inside a gentleman's watch case or snuff-box, the mass-produced equivalent of portrait miniatures. For threepence, or sixpence "neatly coloured", a man could carry his favourite harlot around with him in perfect privacy, gazing upon her whenever he felt like it. The foundations of today's celebrity sex scandals were laid a long time ago.

❦

The ultimate legacy of the first sexual revolution has been far from straightforward. In place of a relatively coherent, authoritative worldview that had endured for centuries, it left a much greater confusion of moral perspectives, with irresolvable tensions between them. That has been part of our modern condition ever since. What's more, as the history of the past few decades shows, its consequences are still unfolding, in different ways across different western societies. It is equally clear that the 18th century marked the point at which the sexual culture of the west as a whole moved on to a new trajectory.

In many parts of the world, by contrast, sexual ideals and practices reminiscent of pre-modern Europe continue to be upheld. Men and (especially) women remain at risk of public prosecution for having sex outside marriage. Often, the word of God is supposed to justify this. The Ayatollah Khomeini affirmed in 1979 that the execution of prostitutes, adulterers and homosexuals was as justified in a moral society as the amputation of gangrenous flesh. In some countries, imprisonment, flogging and execution by hanging, or even by stoning, continues to be imposed on men and women convicted of extramarital or homosexual relations. Even more widespread and deep-rooted is the extra-legal persecution of men and women for such matters. These are the same practices that sustained western culture for most of its history. They rest on very similar foundations – the theocratic authority of holy texts and holy men, intolerance of religious and social pluralism, fear of sexual freedom, and the belief that men alone should govern. How they help to maintain patriarchal social order is obvious; so too is their cost to human happiness. How durable they will prove to be remains to be seen.

Adulterers and prostitutes could be executed and women were agreed to be more libidinous than men – then in the 18th century attitudes to sex underwent an extraordinary change

Faramerz Dabhoiwala

guardian.co.uk, Friday 20 January 2012 22.55 GMT

The rise of sexual freedom … detail from The Bed, etching, engraving and drypoint by Rembrandt (1646). Photograph: © Trustees of the British Museum

We believe in sexual freedom. We take it for granted that consenting men and women have the right to do what they like with their bodies. Sex is everywhere in our culture. We love to think and talk about it; we devour news about celebrities' affairs; we produce and consume pornography on an unprecedented scale. We think it wrong that in other cultures its discussion is censured, people suffer for their sexual orientation, women are treated as second-class citizens, or adulterers are put to death.

The Origins of Sex: A History of the First Sexual Revolution

by Faramerz Dabhoiwala

Yet a few centuries ago, our own society was like this too. In the 1600s people were still being executed for adultery in England, Scotland and north America, and across Europe. Everywhere in the west, sex outside marriage was illegal, and the church, the state and ordinary people devoted huge efforts to hunting it down and punishing it. This was a central feature of Christian society, one that had grown steadily in importance since late antiquity. So how and when did our culture change so strikingly? Where does our current outlook come from? The answers lie in one of the great untold stories about the creation of our modern condition.

When I stumbled on the subject, more than a decade ago, I could not believe that such a huge transformation had not been properly understood. But the more I pursued it, the more amazing material I uncovered: the first sexual revolution can be traced in some of the greatest works of literature, art and philosophy ever produced – the novels of Henry Fielding and Jane Austen, the pictures of Reynolds and Hogarth, the writings of Adam Smith, David Hume and John Stuart Mill. And it was played out in the lives of tens of thousands of ordinary men and women, otherwise unnoticed by history, whose trials and punishments for illicit sex are preserved in unpublished judicial records. Most startling of all were my discoveries of private writings, such as the diary of the randy Dutch embassy clerk Lodewijk van der Saan, posted to London in the 1690s; the emotional letters sent to newspapers by countless hopeful and disappointed lovers; and the piles of manuscripts about sexual freedom composed by the great philosopher Jeremy Bentham but left unpublished, to this day, by his literary executors. Once noticed, the effects of this revolution in attitudes and behaviour can be seen everywhere when looking at the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. It was one of the key shifts from the pre-modern to the modern world.

❦

Since the dawn of history, every civilisation had punished sexual immorality. The law codes of the Anglo-Saxon kings of England treated women as chattels, but they also forbade married men to fornicate with their slaves, and ordered that adulteresses be publicly disgraced, lose their goods and have their ears and noses cut off. Such severity reflected the Christian church's view of sex as a dangerously polluting force, as well as the patriarchal commonplace that women were more lustful than men and liable to lead them astray. By the later middle ages, it was common in places such as London, Bristol and Gloucester for convicted prostitutes, bawds, fornicators and adulterers to be subjected to elaborate ritual punishments: to have their hair shaved off or to be dressed in especially degrading outfits, severely whipped, displayed in a pillory or public cage, paraded around for public humiliation and expelled for ever from the community.

The reformation brought a further hardening of attitudes. The most fervent Protestants campaigned vigorously to reinstate the biblical death penalty for adultery and other sexual crimes. Wherever Puritan fundamentalists gained power, they pursued this goal – in Geneva and Bohemia, in Scotland, in the colonies of New England and in England itself. After the Puritans had led the parliamentary side to victory in the English civil war, executed the King and abolished the monarchy, they passed the Adultery Act of 1650. Henceforth, adulterers and incorrigible fornicators and brothel-keepers were simply to be executed, as sodomites and bigamists already were.

Of course, sexual discipline was never perfect. Men and women constantly gave way to temptation – and then had to be flogged, imprisoned, fined and shamed to reform them. Many others, especially the wealthy and powerful, escaped punishment. As was the case with other crimes, the full rigour of the law was never uniformly or consistently applied. All the same, sexual discipline was a central facet of pre-modern western society, and its unceasing promotion had a profound effect on ordinary men and women. Most people internalised its principles deeply and participated in the disciplining of others. There was no coherent philosophy of sexual liberty, no way of conceiving of a society without moral policing. It seemed obvious that illicit sex had to be combated because it angered God, prevented salvation, damaged personal relations and undermined social order. Sex was emphatically not a private affair.

So pervasive was this ideology that even those who paid with their lives for defying it could not escape its hold over their minds and actions. When the Massachusetts settler James Britton fell ill in the winter of 1644, he became gripped by a "fearful horror of conscience" that this was God's punishment on him for his past sins. So he publicly confessed that once, after a night of heavy drinking, he had tried (but failed) to have sex with a young bride, Mary Latham. Though she now lived far away, in Plymouth colony, the magistrates there were alerted. She was found, arrested and brought back, across the icy landscape, to stand trial in Boston. When, despite her denial that they had actually had sex, she was convicted of adultery, she broke down, confessed it was true, "proved very penitent, and had deep apprehension of the foulness of her sin … and was willing to die in satisfaction to justice". On 21 March, a fortnight after her sentence, she was taken to the public scaffold. Britton was executed alongside her; he, too, "died very penitently". In the shadow of the gallows, Latham addressed the assembled crowds, exhorting other young women to be warned by her example, and again proclaiming her abhorrence and penitence for her terrible crime against God and society. Then she was hanged. She was 18 years old.

❦

That is the world we have left behind. Over the following century and a half it was transformed by a great revolution that laid the ground for the sexual culture of the 19th and 20th centuries, and of our own day.

The most obvious change was a surge in pre- and extramarital sex. We can measure this, crudely but unmistakably, in the numbers of children conceived out of wedlock. During the 17th century this figure had been extremely low: in 1650 only about 1% of all births in England were illegitimate. But by 1800, almost 40% of brides came to the altar pregnant, and about a quarter of all first-born children were illegitimate. It was to be a permanent change in behaviour.

Just as striking was the collapse of public punishment, which made this new sexual freedom possible. By 1800, most forms of consensual sex between men and women had come to be treated as private, beyond the reach of the law. This extraordinary reversal of centuries of severity was partly the result of increasing social pressures. The traditional methods of moral policing had evolved in small, slow, rural communities in which conformity was easy to enforce. Things were different in towns, especially in London. At the end of the middle ages only about 40,000 people lived there, but by 1660 there were already 400,000; by 1800 there would be more than a million, and by 1850 most of the British population lived in towns. This extraordinary explosion created new kinds of social pressures and new ways of living, and placed the conventional machinery of sexual discipline under growing strain.

Urban living provided many more opportunities for sexual adventure. It also gave rise to new, professional systems of policing, which prioritised public order. Crime became distinguished from sin. And the fast circulation of news and ideas created a different, freer and more pluralist intellectual environment.

This was crucial to the development of the ideal of sexual freedom. By the later 18th century, for the first time, many serious observers had come to take it for granted that sex was a private matter, that men and women should be free to indulge in it irrespective of marriage, and that sexual pleasure should be celebrated as one of the purposes of life. As well as reinterpreting the Bible, they found support in new ideas about the importance of personal conscience and in the laws of nature, which were regarded as more clearly indicative of God's will than the inherited dogma of the church and the text of the scriptures. In his 1730 work, Christianity as Old as the Creation, the Oxford don Matthew Tindal ridiculed traditional sexual norms as priestly inventions, no more appropriate to a modern state than the biblical prohibitions against drinking blood or lending money: "Enjoying a woman, or lusting after her, can't be said, without considering the circumstances, to be either good or evil. That warm desire, which is implanted in human nature, can't be criminal, when perused after such a manner as tends most to promote the happiness of the parties, and to propagate and preserve the species."

In a similar vein, the Rev Robert Wallace, one of the leaders of the Church of Scotland in the mid-18th century, wrote a treatise seriously commending "a much more free commerce of the sexes". By that he meant complete liberty for people to cohabit successively with as many partners as they liked – "A woman's being enjoyed by a dozen … can never render her less fit or agreeable to a 13th". As John Wilkes's 1754 Essay on Woman put it: "Life can little more supply / Than just a few good Fucks, and then we die."

❦

It's no accident that all these early celebrations of the new sexual world were voiced by white, upper-class men. In practice, sexual liberty was limited in important ways. The bastardy laws continued to apply to the labouring classes: their morals remained a public matter. The new permissiveness towards "natural" freedoms also led to a sharper definition and abhorrence of supposedly "unnatural" behaviour. Homosexual acts in particular came to be persecuted with increasing violence: throughout the 18th century there were regular executions for sodomy. Even after 1830, when hanging for the offence was ended, thousands of men were publicly humiliated in the pillory, or sentenced to jail, for their unnatural perversions – Oscar Wilde's imprisonment with hard labour for two years in 1895 is only the best-known example.

Yet the general advance of sexual freedom and the expansion of urban life also fostered the development of an increasingly assertive homosexual sub-culture. Some of the most remarkable utterances of the 18th century were the first principled defences of same-sex behaviour as natural, universal and harmless. One night in 1726, William Brown, a married man, was arrested at a notorious pick-up spot with another man's hand in his breeches. When surrounded by hostile watchmen and challenged as to "why he took such indecent liberties … he was not ashamed to answer, 'I did it because I thought I knew him, and I think there is no crime in making what use I please of my own body'". That sodomy had been accepted by all the greatest civilisations of the world was one of the themes of the young clergyman Thomas Cannon's Ancient and Modern Pederasty (1749). "Every dabbler knows by his classics," he pointed out, "that boy-love ever was the top refinement of most enlightened ages." Arguments of the same kind were developed systematically by the Yorkshire gentlewoman Anne Lister (1791-1840), who set down in her diaries the first full justification of lesbian love in English, and by Bentham, the most influential reformer of the age, who defended the rights of homosexuals in countless private discussions and over many hundreds of pages of notes and treatises.

Attitudes towards women's sexuality underwent similarly dramatic shifts. The idea that sexual freedom was as natural and desirable for women as for men was born in the 18th century. By the early 19th century, many feminists, socialists and other progressive thinkers on both sides of the Atlantic decried marriage and advocated free love as a means to the emancipation of women and the creation of a more just society. Among those who held such views were Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor, Robert Owen and many Owenites, and Percy Bysshe Shelley. In the long term, this egalitarian way of thinking was to provide the intellectual foundation for women's sexual liberation more generally.

Yet more immediately the rise of sexual freedom had a much more ambiguous legacy. Women who were rich or powerful enough to escape social ostracism could take advantage of it: many female aristocrats had notoriously open marriages. But on the whole female lust now came to be ever more strongly stigmatised as "unnatural", for it threatened the basic principle that (as one of William III's bishops had put it) "Men have a property in their wives and daughters" and therefore owned their bodies too. Thus, at the same time as it was increasingly argued that sexual liberty was natural for men, renewed stress was placed, often in the same breath, on the necessity of chastity in respectable women.

The effects of this sharpened double standard can be seen everywhere in 18th-, 19th- and 20th-century culture. James Boswell's diary records the tragic story of Jean, the brilliant only daughter of Henry Home, Lord Kames, one of the leading thinkers of the Enlightenment. In the early 1760s, when she was only 16 or 17 and already married, she embarked on a passionate affair with Boswell, arguing to him that they were doing nothing wrong:

"She was a subtle philosopher. She said, 'I love my husband as a husband, and you as a lover, each in his own sphere. I perform for him all the duties of a good wife. With you, I give myself up to delicious pleasures. We keep our secret. Nature has so made me that I shall never bear children. No one suffers because of our loves. My conscience does not reproach me, and I am sure that God cannot be offended by them.'"

A decade later, when her husband divorced her over another affair, she declared "that she hoped that God Almighty would not punish her for the only crime she could charge herself with, which was the gratification of those passions which he himself had implanted in her nature." But her father, the scholar and moral authority, took the conventional view that adultery in a man "may happen occasionally, with little or no alienation of affection", but in a woman was unpardonable. After his daughter's divorce, he and Lady Kames exiled her to France and never saw her again.

❦

Indeed, the first sexual revolution was characterised by an extraordinary reversal in assumptions about female sexuality. Ever since the dawn of western civilisation it had been presumed that women were the more lustful sex. As they were mentally, morally and physically weaker than males, it followed that they were less able to control their passions and thus (like Eve) more likely to tempt others into sin. Yet, by 1800, exactly the opposite idea had become entrenched. Now it was believed that men were much more naturally libidinous and liable to seduce women. Women had come to be seen as comparatively delicate and sexually defensive, needing to be constantly on their guard against male rapacity. The notion of women's relative sexual passivity became fundamental to sexual dynamics across the western world. Its effects were ubiquitous – they still are.

A crucial reason was the rise of women as public writers, which introduced into the cultural mainstream powerful new female perspectives on courtship and lust. This was an unprecedented development. In all earlier times, women's direct intervention in public discussion had been very limited. Men monopolised every medium in which male and female qualities were prescribed and reinforced – fiction, drama, poetry, sermons, journalism and so on. But from the later 17th century onwards, women emerged for the first time as a permanent part of the world of letters. As playwrights, poets, novelists and philosophers, women influenced male authors, looked to one another, and addressed themselves directly to the public. And in much female writing about sexual relations, the bottom line was, as the teenage poet Sarah Fyge explained in 1686, that men were always trying "to make a prey" of chaste women. Male bluster about female lust was but to make women "the scapegoat" – it was men who constantly pressured and ensnared women, who were insatiable in their thirst for new conquests, and shameless in their commission. As the feminist Mary Astell put it bitterly in 1700, "'Tis no great matter to them if women, who were born to be their slaves, be now and then ruined for their entertainment". No woman could ever "be too much upon her guard".

None of these ideas was entirely new, but it was only from around 1700 that they came to be put forward publicly, in a way that discernibly changed the culture of the age. Especially influential in the long term was the role of women in creating the new genre of the novel, which by the middle of the 18th century had become the most influential fictional form and become a central conduit of moral and social education. Samuel Johnson noted in 1750 that women's breaking of the male monopoly on writing, and their "stronger arguments", had overturned the ancient masculine falsehood that women were the more fickle and lecherous sex.

All this explains why the first major novelists of the English language were so obsessed with seduction. Samuel Richardson, whose Pamela, Clarissa and Sir Charles Grandison were the most sensationally popular and influential pieces of fiction of the 18th century, was a classic instance of the growing power of female viewpoints. For all its originality, the general approach and subject matter of his fiction owes an obvious debt to the stream of earlier novels about heroines courted, seduced, raped and oppressed, which had flowed from the pens of pioneering female writers such as Penelope Aubin, Jane Barker, Mary Davys, Eliza Haywood and Elizabeth Rowe. A wide circle of women acquaintances, readers and correspondents helped him; in turn, his work presented eyewitness perspectives of respectable women under threat from rapacious superior men. Right through the 19th century, it is hard to think of many serious novelists who did not pursue the seduction narrative.

❦

Equally important to modern ways of thinking was the increasing sexualisation of race and class. The presumption that lower-class and non-white women were less sexually restrained became a matter of both investigation and titillation. As sexual norms were increasingly held to vary according to race, class and sex, so the transgression of such boundaries (in reality and in fantasy) became ever more erotically charged. This was the origin of the great British obsession with sex and class, which equally affected homosexual passion. "We don't like people like ourselves," explains a middle-class character in one 1950s novel about gay lust. "We don't want anybody who shares our standards. In fact, we want the very opposite. We want the primitive, the uneducated, the tough." Even some of the most basic features of our sexual desire are therefore not natural and unchanging, but historically created. What we think of as "natural" in men and women, where the boundaries lie between the normal and the deviant, how we feel about the pursuit of pleasure and the transgression of sexual norms – all these are matters on which our current attitudes are fundamentally different from those that have prevailed for most of western history.

The new fascination with class and licentiousness helped to transform attitudes towards prostitution. The conventional view had been that prostitutes were the worst reprobates of all, deserving of the harshest punishments. But from the middle of the 18th century this perspective was matched, and often overshadowed, by the presumption that prostitutes themselves were ultimately the innocent victims of male lust and social deprivation. Vast efforts were poured into the foundation of asylums, workhouses and other charities for fallen women and girls at risk of seduction. Many contemporaries saw obvious parallels between black and white slavery. "What are the sorrows of the enslaved negro from which the outcast prostitute of London is exempted?" asked one late-Georgian activist. "A seducer or ravisher has torn them both, for ever, from the abodes of their youth … Is the bosom of the unhappy girl less tender than that of the swarthy savage?"

The rescue of fallen women, and the abolition of "white slavery", consequently became a craze to which some of the most prominent figures in public life devoted great energy. At the height of his fame, Charles Dickens threw himself into the foundation of a refuge for penitents, with the financial backing of the millionairess Angela Burdett-Coutts. His fellow novelist George Gissing tried (and failed) to redeem a young prostitute by marrying her himself. William Gladstone called the issue "the chief burden of my soul", and for decades, even while prime minister, roamed the streets at night attempting to save prostitutes.

❦

The final notable feature of the first sexual revolution was the birth of a new kind of media culture, in which private affairs and personal opinions were given unprecedented publicity. The explosion of publishing created a much more democratic and permanent network of public communication than had ever existed before. The mass proliferation of newspapers and magazines, and a new-found fascination with the boundaries of the private and the public, combined to produce the first age of sexual celebrity. The sayings and doings of famous courtesans now came to be routinely analysed in print, and their portraits were endlessly painted, engraved and caricatured. Many of them skilfully promoted themselves, keeping their names and faces in the public eye by publishing memoirs and publicising their image. By the middle of the 18th century, a visitor to any of London's print shops could have bought dozens of different portraits, in all shapes and sizes, of Kitty Fisher, Fanny Murray, Nancy Dawson and every other well-known lady of pleasure. Cheapest of all were tiny prints made to fit inside a gentleman's watch case or snuff-box, the mass-produced equivalent of portrait miniatures. For threepence, or sixpence "neatly coloured", a man could carry his favourite harlot around with him in perfect privacy, gazing upon her whenever he felt like it. The foundations of today's celebrity sex scandals were laid a long time ago.

❦

The ultimate legacy of the first sexual revolution has been far from straightforward. In place of a relatively coherent, authoritative worldview that had endured for centuries, it left a much greater confusion of moral perspectives, with irresolvable tensions between them. That has been part of our modern condition ever since. What's more, as the history of the past few decades shows, its consequences are still unfolding, in different ways across different western societies. It is equally clear that the 18th century marked the point at which the sexual culture of the west as a whole moved on to a new trajectory.

In many parts of the world, by contrast, sexual ideals and practices reminiscent of pre-modern Europe continue to be upheld. Men and (especially) women remain at risk of public prosecution for having sex outside marriage. Often, the word of God is supposed to justify this. The Ayatollah Khomeini affirmed in 1979 that the execution of prostitutes, adulterers and homosexuals was as justified in a moral society as the amputation of gangrenous flesh. In some countries, imprisonment, flogging and execution by hanging, or even by stoning, continues to be imposed on men and women convicted of extramarital or homosexual relations. Even more widespread and deep-rooted is the extra-legal persecution of men and women for such matters. These are the same practices that sustained western culture for most of its history. They rest on very similar foundations – the theocratic authority of holy texts and holy men, intolerance of religious and social pluralism, fear of sexual freedom, and the belief that men alone should govern. How they help to maintain patriarchal social order is obvious; so too is their cost to human happiness. How durable they will prove to be remains to be seen.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: On Love

Re: On Love

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OkyUtkpk73k&feature=related

Turned Up Too Late- Graham Parker & The Rumour.

Turned Up Too Late- Graham Parker & The Rumour.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: On Love

Re: On Love

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2796pBfrK-U&feature=related

I'm a Man You Don't Meet Every Day- The Pogues. The future Mrs Elvis Costello on vocals.

I'm a Man You Don't Meet Every Day- The Pogues. The future Mrs Elvis Costello on vocals.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: On Love

Re: On Love

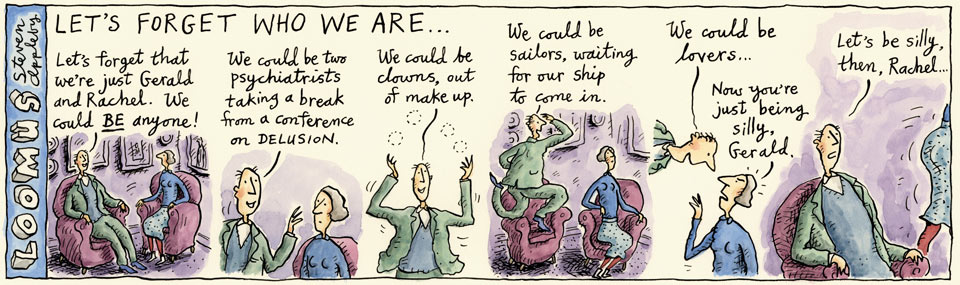

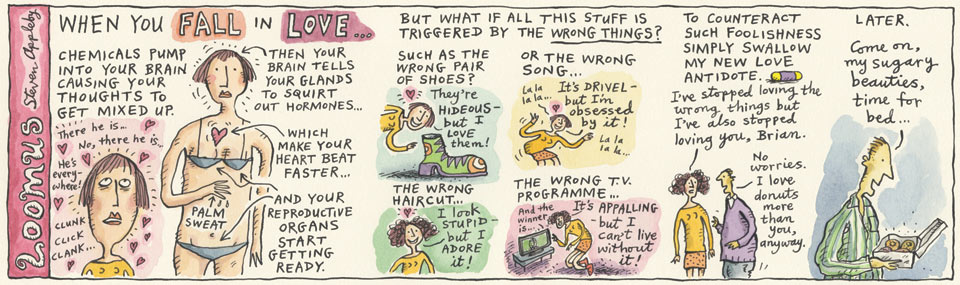

Steven Appleby.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: On Love

Re: On Love

In an attempt to travel cheap sometimes I say "let's forget we are in Spain"... it is strange because it works a bit...

Guest- Guest

Re: On Love

Re: On Love

The Monogamy Gap: Men, Love and the Reality of Cheating by Eric Anderson – review

Eric Anderson's survey of male promiscuity is persuasive – but has a few obvious holes

Catherine Hakim

guardian.co.uk, Thursday 1 March 2012 11.55 GMT

Eric Anderson sees casual sex as different from affairs - a view many wives would challenge. Photograph: Franco Vogt/Corbis

The title of this book should really be Cheat's Charter. It is a hoot, and would appeal to readers of lads' mags, if they could only ignore the ponderous sociological jargon designed to show high intellectual aims. Anderson argues that male sexual cheating is ubiquitous; that men cheat "because they love their partners" (although what he actually means is "despite loving them"); that women should understand and accept this; that western rules of fidelity and monogamy impose intolerable and irrational constraints on men's innate, lifelong, somatic need for sexual exploration and adventure; that almost all men become sexually bored with their partner roughly two years into a relationship when they decide they need more diversity and novelty; and that open sexual relationships are the only solution – for men at least.

The Monogamy Gap: Men, Love, and the Reality of Cheating (Sexuality, Identity, and Society)

by Eric Anderson

Anderson is an American sociologist who specialises in sexuality and sport, partly because he is gay and was a distance runner as a teenager. This explains why his study of cheating behaviour and rationales relies on interviews with 120 male university students aged 18-22, but focusing on American soccer stars. These young men are athletes at their physical peak, who live in a utopian sexual marketplace, with young women often throwing themselves at them, just as some young women groupies in Britain seek to sleep with all members of top football teams. By defining cheating broadly enough to include kissing, touching and flirting, he finds that four-fifths of these young men cheat on their partners, especially when they are playing away from their home base. He claims that pretty well all young men, heterosexual and gay, will cheat sooner or later if they possibly can, and that opportunity and deniability are the primary factors.

His argument has some support in the recent national sex surveys showing that men want sex more than women do. The result is the male sex deficit, as I call it in my book Honey Money – male demand outstrips female supply, overall, in the heterosexual community. Anderson does not really have an answer to this problem, because he effectively ignores women, and relies heavily on his knowledge of gay cultures. It works for them, so why not for heterosexuals too?

Anderson sees regular casual sex with a variety of people (which he recommends) as different from affairs (involving dating and romance), which he regards as emotional betrayal. This distinction may apply among gay men, where impersonal and spontaneous sex is not uncommon, but most heterosexual wives and girlfriends would question this finesse – as even he admits in several of his anecdotes about men who were caught in the act by their enraged girlfriends.