Biography and Autobiography

+2

ISN

eddie

6 posters

Page 2 of 2

Page 2 of 2 •  1, 2

1, 2

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Happy Van welcoming yet another book written about him.

Lee Van Queef- Posts : 511

Join date : 2011-04-15

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Once upon a life: Ali Smith

Looking back on her life, writer Ali Smith returns to the moment of conception to weave a poignant and funny memoir of an irreverent father, a weakness for Greek musicals and a fateful border crossing

Ali Smith The Observer, Sunday 29 May 2011

“July 1963. I am 11 months old”: Ali Smith with her father and four siblings as they cross the border into England

December 1961: I am conceived! And I don't remember a thing about it. I'm even having to guess what day of the week it is: a Monday, a Tuesday, a Wednesday, who knows, though it's probably more likely to be a couple of weekends before Christmas, but even so God knows how it comes about since there are two brothers and two sisters already out there over the border none of us remembers crossing, between not here and here, and I'm pretty sure nobody was planning on me since they were all born one year apart, and my nearest brother is now six, and my mother, all through my childhood, will refer to me laughingly as her surprise, and my father, nearly 50 years later when he's in his mid-80s and not long for this world, will tell me they were glad after all that they'd had a late child. It kept us young.

But that's not for ages, that's 48 years later; right now it's not that long since my mother persuaded my father to give up smoking and become a Catholic (which is quite a double whammy); it's dark, they're probably in their bed in our house at 92 St Valery, in Inverness, Scotland, one of the new council houses running along the back of the Caledonian Canal, a house they were lucky enough to get after the war, which my dad apparently pulled off by giving one of my (very small) sisters a good nip in the leg when he and my mother were called through for their tenancy interview, making my sister cry furiously throughout, making the council people keen to give them a house just to get rid of them.

My father is an electrician; he learned his trade as a boy in the war, in the Navy, and met my mother when she was a WAF. Now he has a contractor's business and a shop. He wires houses all up and down the Highlands. Their names are Don and Ann. My father is from Newark in Nottinghamshire and my mother is from the very north of Ireland. They've ended up in Scotland, where my father – well, both of them – will always be seen as having come from somewhere else. This is one of the things that makes it possible, I see much later, for my father to go into the house of one of our neighbours who's dying of cancer, and make the man erupt into joyous laughter when he crosses the line, says it out loud, the unsayable: What's this, Andy, not dead yet?

But that, as I say, is later. Right now out in the world there are riots in Paris, there are new push-button pedestrian crossings introduced in London, there are escapes from Alcatraz – three prisoners on a raft made of raincoats. There's an American rocket on the moon for the first time, but it can't send back any pictures because something goes wrong with its camera. There's a man called John Glenn who orbits the world for the first time in a spaceship called Friendship 7. There's a girl found dead in her bed in America, Norma Jeane Mortenson, Marilyn. And in Greece there's a film musical starring Aliki Vougiouklaki which everybody all over that country is whistling the tunes from, since it's the year's biggest cinema grosser. Not that I'll know Aliki Vougiouklaki even exists until 30-odd years later, when I will be idly watching Greek TV one evening on holiday, and will come upon this film and love it. Not that I'll know then that 10 years on, in 2010, when I'm in what I suppose is a quite deep depression after my dad dies (my mum will have died 20 years earlier), that one of the things that will get me through this dark time will be watching a lot of snippets, in the middle of the night, of bright benign Greek musicals starring the evanescent Vougiouklaki, on YouTube. Trava bros! she sings in 1961, when I'm an embryo. Move on, don't worry about a thing. We should live bravely, our life is short. The world's a big wheel, it keeps turning. Move on, don't think twice.

August 1962. I am born, about two and a half weeks early! And I can't remember a thing about it. I am born at three in the morning on the anniversary of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, the feast day of St Bartholomew, patron saint of tanners, shoemakers, butchers and skinners, which is why he's always depicted holding a knife, and sometimes a leather-bound book, and even sometimes with his own skin draped over his arm (they martyred him by flaying him alive). Not long after I am born I am covered in eczema, and it proves extremely difficult to cure as I'm resistant to Betnovate.

Other things told to me later: You were adopted. The choice was between you and a monkey. But by the time Mum and Dad got to the adoption place, the monkey had already been taken. When you were born you were the size of a bag and a half of sugar. Before you were born none of the neighbours knew Mum was going to have you, because you were so small.

A game one of my sisters will play with me in my first year of being alive is called Good Baby, Bad Baby. This consists of being told I am a good baby until I smile and laugh, then being told I am a bad baby until I burst into tears. This training will stand me in good stead all through my life.

July 1963. I am 11 months old! And I remember nothing about it. But there's a photo of us all on holiday, it is summer, we're grouped round the England sign – my first visit to England, where I'll live for much of my adult life, not that I'll believe you if you tell me, in my teens, that this is likely to happen. In it, there's no sign of eczema and I am presumably already both a good baby and a bad baby. In it my father is 10 years younger than I am now, surrounded so sweet and so sure by his children, and all of us casually artfully arranged by my mother, who's taking the photo.

Look at us all, caught between the countries. Look at me. One day I will look back through my mother's eye and see myself there most clearly, not in my own face, but in my father's.

Over the borders, here we come. Here we go.

Ali Smith's novel There But For The is published by Hamish Hamilton at £16.99

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Looking back on her life, writer Ali Smith returns to the moment of conception to weave a poignant and funny memoir of an irreverent father, a weakness for Greek musicals and a fateful border crossing

Ali Smith The Observer, Sunday 29 May 2011

“July 1963. I am 11 months old”: Ali Smith with her father and four siblings as they cross the border into England

December 1961: I am conceived! And I don't remember a thing about it. I'm even having to guess what day of the week it is: a Monday, a Tuesday, a Wednesday, who knows, though it's probably more likely to be a couple of weekends before Christmas, but even so God knows how it comes about since there are two brothers and two sisters already out there over the border none of us remembers crossing, between not here and here, and I'm pretty sure nobody was planning on me since they were all born one year apart, and my nearest brother is now six, and my mother, all through my childhood, will refer to me laughingly as her surprise, and my father, nearly 50 years later when he's in his mid-80s and not long for this world, will tell me they were glad after all that they'd had a late child. It kept us young.

But that's not for ages, that's 48 years later; right now it's not that long since my mother persuaded my father to give up smoking and become a Catholic (which is quite a double whammy); it's dark, they're probably in their bed in our house at 92 St Valery, in Inverness, Scotland, one of the new council houses running along the back of the Caledonian Canal, a house they were lucky enough to get after the war, which my dad apparently pulled off by giving one of my (very small) sisters a good nip in the leg when he and my mother were called through for their tenancy interview, making my sister cry furiously throughout, making the council people keen to give them a house just to get rid of them.

My father is an electrician; he learned his trade as a boy in the war, in the Navy, and met my mother when she was a WAF. Now he has a contractor's business and a shop. He wires houses all up and down the Highlands. Their names are Don and Ann. My father is from Newark in Nottinghamshire and my mother is from the very north of Ireland. They've ended up in Scotland, where my father – well, both of them – will always be seen as having come from somewhere else. This is one of the things that makes it possible, I see much later, for my father to go into the house of one of our neighbours who's dying of cancer, and make the man erupt into joyous laughter when he crosses the line, says it out loud, the unsayable: What's this, Andy, not dead yet?

But that, as I say, is later. Right now out in the world there are riots in Paris, there are new push-button pedestrian crossings introduced in London, there are escapes from Alcatraz – three prisoners on a raft made of raincoats. There's an American rocket on the moon for the first time, but it can't send back any pictures because something goes wrong with its camera. There's a man called John Glenn who orbits the world for the first time in a spaceship called Friendship 7. There's a girl found dead in her bed in America, Norma Jeane Mortenson, Marilyn. And in Greece there's a film musical starring Aliki Vougiouklaki which everybody all over that country is whistling the tunes from, since it's the year's biggest cinema grosser. Not that I'll know Aliki Vougiouklaki even exists until 30-odd years later, when I will be idly watching Greek TV one evening on holiday, and will come upon this film and love it. Not that I'll know then that 10 years on, in 2010, when I'm in what I suppose is a quite deep depression after my dad dies (my mum will have died 20 years earlier), that one of the things that will get me through this dark time will be watching a lot of snippets, in the middle of the night, of bright benign Greek musicals starring the evanescent Vougiouklaki, on YouTube. Trava bros! she sings in 1961, when I'm an embryo. Move on, don't worry about a thing. We should live bravely, our life is short. The world's a big wheel, it keeps turning. Move on, don't think twice.

August 1962. I am born, about two and a half weeks early! And I can't remember a thing about it. I am born at three in the morning on the anniversary of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, the feast day of St Bartholomew, patron saint of tanners, shoemakers, butchers and skinners, which is why he's always depicted holding a knife, and sometimes a leather-bound book, and even sometimes with his own skin draped over his arm (they martyred him by flaying him alive). Not long after I am born I am covered in eczema, and it proves extremely difficult to cure as I'm resistant to Betnovate.

Other things told to me later: You were adopted. The choice was between you and a monkey. But by the time Mum and Dad got to the adoption place, the monkey had already been taken. When you were born you were the size of a bag and a half of sugar. Before you were born none of the neighbours knew Mum was going to have you, because you were so small.

A game one of my sisters will play with me in my first year of being alive is called Good Baby, Bad Baby. This consists of being told I am a good baby until I smile and laugh, then being told I am a bad baby until I burst into tears. This training will stand me in good stead all through my life.

July 1963. I am 11 months old! And I remember nothing about it. But there's a photo of us all on holiday, it is summer, we're grouped round the England sign – my first visit to England, where I'll live for much of my adult life, not that I'll believe you if you tell me, in my teens, that this is likely to happen. In it, there's no sign of eczema and I am presumably already both a good baby and a bad baby. In it my father is 10 years younger than I am now, surrounded so sweet and so sure by his children, and all of us casually artfully arranged by my mother, who's taking the photo.

Look at us all, caught between the countries. Look at me. One day I will look back through my mother's eye and see myself there most clearly, not in my own face, but in my father's.

Over the borders, here we come. Here we go.

Ali Smith's novel There But For The is published by Hamish Hamilton at £16.99

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Re: Biography and Autobiography

^

I've updated the rather scappy first page of this thread, replacing some links with actual text and images and replacing the expired links with new recommendations.

I've updated the rather scappy first page of this thread, replacing some links with actual text and images and replacing the expired links with new recommendations.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Mark Vonnegut (sun of Kurt) - The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity (1975)

From Amazon.com:

From Amazon.com:

Product Description

The Eden Express describes from the inside Mark Vonnegut’s experience in the late ’60s and early ’70s—a recent college grad; in love; living communally on a farm, with a famous and doting father, cherished dog, and prized jalopy—and then the nervous breakdowns in all their slow-motion intimacy, the taste of mortality and opportunity for humor they provided, and the grim despair they afforded as well. That he emerged to write this funny and true book and then moved on to find the meaningful life that for a while had seemed beyond reach is what ultimately happens in The Eden Express. But the real story here is that throughout his harrowing experience his sense of humor let him see the humanity of what he was going through, and his gift of language let him describe it in such a moving way that others could begin to imagine both its utter ordinariness as well as the madness we all share.

About the Author

After writing The Eden Express, MARK VONNEGUT went to medical school. He lives with his wife and two children in Milton, Mass., where he is a full-time practicing pediatrician.

felix- cool cat - mrkgnao!

- Posts : 836

Join date : 2011-04-11

Location : see the chicken?

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Re: Biography and Autobiography

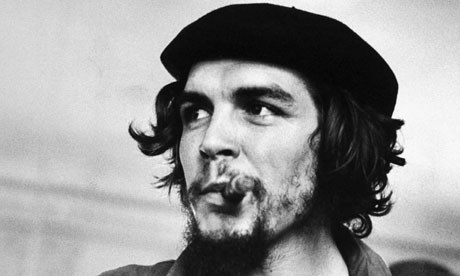

Pass notes, No 2,994: Che Guevara

The Argentinian revolutionary is publishing a set of diaries, 44 years after his death

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 15 June 2011 19.59 BST

Che Guevara. Photograph: Joseph Scherschel

Age:

83 years (39 of them alive).

Appearance:

Bloody everywhere.

Not him again.

Yes, him again. Argentinian rugby player, doctor, writer, soldier, politician, freelance revolutionary, beret model and father of five, Ernesto "Che" Guevara. The coolest man ever to not quite grow a beard.

You forgot "self-starter".

Thanks. Anyway, he's got a new book out.

Recipes for busy parents?

Sadly, no. It's an unpublished set of diaries.

Oh well, I suppose writing anything is impressive from a dead person. How did he manage it?

Well, the actual writing part he did while he was still alive.

Clever.

And his widow's been sitting on it since his execution in 1967. The book was released on Tuesday in Havana, she said, "to show his work, his thoughts, his life, so that the Cuban people and the entire world get to know him and don't distort things any more".

Very wise. If you want to put a stop to tittle-tattle, you really need to get your story out within the first 44 years. What are these diaries about?

Revolution.

You don't say.

I do. Guevara started writing them in 1956 shortly after landing in Cuba, with Castro, on board the yacht Granma. They describe the following two years, which he spent travelling around the island's mountainous interior, conducting a guerrilla war to overthrow the Batista regime.

In a jeep called Grandad? That seems unlikely.

You'll have to read the book.

Any chance of a precis?

Did some war . . . Read Sartre to campesinos . . . Smoked pipe, thinking about US imperialism . . . Did a bit more war . . . Executed traitor . . . War's going well today . . . Adjusted beret . . .

I can't bear the tension.

Don't worry. He wins in the end.

Do say:

"'Che' is an Argentinian slang term, roughly equivalent in use to the way that some English speakers place 'man' at the beginning or end of sentences. Guevara used the word so frequently during his time in Guatemala that he acquired it as a nickname.

Don't say:

"If you tremble with indignation at every injustice, then you are a comrade of mine, man."

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

The Argentinian revolutionary is publishing a set of diaries, 44 years after his death

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 15 June 2011 19.59 BST

Che Guevara. Photograph: Joseph Scherschel

Age:

83 years (39 of them alive).

Appearance:

Bloody everywhere.

Not him again.

Yes, him again. Argentinian rugby player, doctor, writer, soldier, politician, freelance revolutionary, beret model and father of five, Ernesto "Che" Guevara. The coolest man ever to not quite grow a beard.

You forgot "self-starter".

Thanks. Anyway, he's got a new book out.

Recipes for busy parents?

Sadly, no. It's an unpublished set of diaries.

Oh well, I suppose writing anything is impressive from a dead person. How did he manage it?

Well, the actual writing part he did while he was still alive.

Clever.

And his widow's been sitting on it since his execution in 1967. The book was released on Tuesday in Havana, she said, "to show his work, his thoughts, his life, so that the Cuban people and the entire world get to know him and don't distort things any more".

Very wise. If you want to put a stop to tittle-tattle, you really need to get your story out within the first 44 years. What are these diaries about?

Revolution.

You don't say.

I do. Guevara started writing them in 1956 shortly after landing in Cuba, with Castro, on board the yacht Granma. They describe the following two years, which he spent travelling around the island's mountainous interior, conducting a guerrilla war to overthrow the Batista regime.

In a jeep called Grandad? That seems unlikely.

You'll have to read the book.

Any chance of a precis?

Did some war . . . Read Sartre to campesinos . . . Smoked pipe, thinking about US imperialism . . . Did a bit more war . . . Executed traitor . . . War's going well today . . . Adjusted beret . . .

I can't bear the tension.

Don't worry. He wins in the end.

Do say:

"'Che' is an Argentinian slang term, roughly equivalent in use to the way that some English speakers place 'man' at the beginning or end of sentences. Guevara used the word so frequently during his time in Guatemala that he acquired it as a nickname.

Don't say:

"If you tremble with indignation at every injustice, then you are a comrade of mine, man."

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Re: Biography and Autobiography

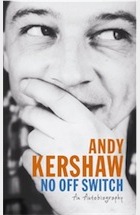

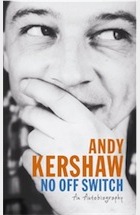

I liked Andy Kershaw as a broadcaster so it's very sad to learn that he's apparently become so bitter and twisted:

**********************************************************************************

No Off Switch by Andy Kershaw – review

Andy Kershaw travelled the world to bring his radio audience exciting new sounds. It's a shame such generous purpose is lacking from his memoir

Rachel Cooke guardian.co.uk, Thursday 30 June 2011 17.19 BST

Andy Kershaw with Radio 4 producer Simon Broughton on the Niger in Mali, 1988. Photograph: Chris Heath

I have personal experience of Andy Kershaw's absent off switch. In March 2008, during the period when, thanks to alcohol and the break-up of his relationship with the mother of his two children, he hit rock bottom, I was dispatched to the Isle of Man to interview him. When I arrived at his house on Peel's seafront, he was not there. Earlier that morning, he'd been arrested for harassing his former partner. The sad part was that he had been released from prison, having served a six-week sentence for a similar offence, only days before.

No Off Switch by Andy Kershaw

I got a taxi to the courthouse in Douglas where Kershaw would appear before the island's high bailiff, Michael Moyle. When he shuffled on to the stand, I was appalled. He looked, and sounded, exactly like a homeless alcoholic: shaky and prematurely old, his tone, as he addressed Moyle, straight out of Little Dorrit, a pathetic combination of resignation and ingratiation (he wanted, desperately, to be allowed to leave). It was pitiful. The man whose radio show soundtracked my teenage evenings brought to this.

Moyle told Kershaw to go home and sort himself out. Meanwhile, I flew back to London. Not all journalists are assassins; I decided it would be kinder to wait for my audience. Kershaw, however, had different ideas. In the days that followed, he left a series of messages on my telephone, long and incoherent. At one point, he revealed that he was staying with his sister, Liz, in Northamptonshire. Would I join him for a fishing trip on a certain riverbank in the middle of nowhere? I consulted my editor. No, I would not. His anger – the only constant in his ramblings – was faintly alarming, to me and to her.

Unfortunately, Kershaw's rage was not some temporary visitation. The last time I read a memoir this replete with self-pity and self-regard – for these are the twin engines of his fury – it was by John Osborne, a fact I find superbly ironic. Kershaw, who styles himself "Mr Global Adventure", has so far tried his hand at buying Dolly Parton albums in 97 countries. Haiti is his idea of paradise. He would no more identify himself as a misanthrope or Little Englander than he would stick Steps on his turntable. Yet his opinions could not be more rigid and archaic if he'd found them down the end of Blackpool pier. He is always right, and those who disagree are always stupid. This starts with his first love, music. The Beatles? Unexciting. Elvis Presley? Manifestly plastic. David Bowie? Self-important. Slade? Now you're talking. Then it gradually extends to include everyone and everything: his former colleagues at BBC Radio 1 (dreadful, craven, stupid); Jools Holland (rubbish); Live Aid (dubious – though that didn't stop him presenting it); feminists (humourless). And let's not forget that "invasive species", the chav. On and on it goes, with the result that the reader feels no surprise at all when he cannot even bring himself to be unequivocally kind about his friend and mentor, John Peel (lily-livered, self-obsessed). Breasts, incidentally, are always referred to as "knockers", and sex as "leg-over".

Kershaw, the son of a headmaster, grew up in Rochdale, where the disappointment set in early, in spite of his genius (at the age of 51, he is still apt to boast about his A-level results, and the fact that, aged two, he could name all the allied generals in his father's history of the great war). The town was suffocatingly parochial, and the private school his parents forced him to attend was full of wankers (aka boys who liked football). Girls? On this score, his troubles were twofold: his height (small), plus their fondness for ELO. Nevertheless, in 1980 he managed to lose his virginity, to the sound – natch – of Van Morrison's Astral Weeks. He departed his economics A-level early to attend a Bob Dylan gig, but he still got – double natch – an "A", and was thus able to take up his place at the University of Leeds, where he read politics and, much more importantly, became entertainment secretary. The Clash, Motörhead, Haircut 100: he booked them all.

The rest – as Kershaw would surely tell you – is history. A stint at Radio Aire was followed by a period driving Billy Bragg around, and this by a job as a presenter of the Old Grey Whistle Test. When that old lady was axed, he went to Radio 1. People said he was John Peel's heir, but that wasn't how he saw it. In fact, he resented the implication that he did not have "musical tastes of my own". He certainly did. Andy, for instance, liked Bruce (Springsteen), an artist of whom Peel was "wilfully dismissive". I won't say much here about his embittered disquisitions on Peel. But I will note that when, in 2004, Peel dies of a heart attack on holiday in Peru, Kershaw's main feeling seems to be: I told you so. (Peel was too fat for high altitudes.)

His attitude to Peel is only matched, in narrative terms, by that towards his ex-partner, Juliette Banner, who is not even mentioned until page 309, though their relationship lasted 17 years. It was Kershaw's idea that they move to the Isle of Man, where they already owned a cottage (the better that he, a bike fanatic, might watch the TT races). But the dream turned sour on their first day, when she borrowed his mobile and discovered on it a message from a woman with whom he'd had a one-night stand at the Womad festival ("it alluded to leg-over in the Reading area"). What followed – Banner had to take out a restraining order against him; his refusal to abide by it led to three stretches in prison, and a period on the run – was miserable: for Kershaw, certainly, but even more so, surely, for his estranged family. Not that he has much sense of this. What strikes you all over again in the scant 30 pages he devotes to this time is his self-pity. No one is as unhappy as Andy. No one hurts as much.

Like many bullies and almost all drunks, Kershaw is nothing if not sentimental. In the war zones from where he occasionally reports for the BBC, he is action man. The piled bodies and human rights abuses seem to faze him not at all. But put on the Oldham Tinkers' "Come Whoam to Thi Childer an' Me", and the tears will flow, copious and unembarrassed.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

**********************************************************************************

No Off Switch by Andy Kershaw – review

Andy Kershaw travelled the world to bring his radio audience exciting new sounds. It's a shame such generous purpose is lacking from his memoir

Rachel Cooke guardian.co.uk, Thursday 30 June 2011 17.19 BST

Andy Kershaw with Radio 4 producer Simon Broughton on the Niger in Mali, 1988. Photograph: Chris Heath

I have personal experience of Andy Kershaw's absent off switch. In March 2008, during the period when, thanks to alcohol and the break-up of his relationship with the mother of his two children, he hit rock bottom, I was dispatched to the Isle of Man to interview him. When I arrived at his house on Peel's seafront, he was not there. Earlier that morning, he'd been arrested for harassing his former partner. The sad part was that he had been released from prison, having served a six-week sentence for a similar offence, only days before.

No Off Switch by Andy Kershaw

I got a taxi to the courthouse in Douglas where Kershaw would appear before the island's high bailiff, Michael Moyle. When he shuffled on to the stand, I was appalled. He looked, and sounded, exactly like a homeless alcoholic: shaky and prematurely old, his tone, as he addressed Moyle, straight out of Little Dorrit, a pathetic combination of resignation and ingratiation (he wanted, desperately, to be allowed to leave). It was pitiful. The man whose radio show soundtracked my teenage evenings brought to this.

Moyle told Kershaw to go home and sort himself out. Meanwhile, I flew back to London. Not all journalists are assassins; I decided it would be kinder to wait for my audience. Kershaw, however, had different ideas. In the days that followed, he left a series of messages on my telephone, long and incoherent. At one point, he revealed that he was staying with his sister, Liz, in Northamptonshire. Would I join him for a fishing trip on a certain riverbank in the middle of nowhere? I consulted my editor. No, I would not. His anger – the only constant in his ramblings – was faintly alarming, to me and to her.

Unfortunately, Kershaw's rage was not some temporary visitation. The last time I read a memoir this replete with self-pity and self-regard – for these are the twin engines of his fury – it was by John Osborne, a fact I find superbly ironic. Kershaw, who styles himself "Mr Global Adventure", has so far tried his hand at buying Dolly Parton albums in 97 countries. Haiti is his idea of paradise. He would no more identify himself as a misanthrope or Little Englander than he would stick Steps on his turntable. Yet his opinions could not be more rigid and archaic if he'd found them down the end of Blackpool pier. He is always right, and those who disagree are always stupid. This starts with his first love, music. The Beatles? Unexciting. Elvis Presley? Manifestly plastic. David Bowie? Self-important. Slade? Now you're talking. Then it gradually extends to include everyone and everything: his former colleagues at BBC Radio 1 (dreadful, craven, stupid); Jools Holland (rubbish); Live Aid (dubious – though that didn't stop him presenting it); feminists (humourless). And let's not forget that "invasive species", the chav. On and on it goes, with the result that the reader feels no surprise at all when he cannot even bring himself to be unequivocally kind about his friend and mentor, John Peel (lily-livered, self-obsessed). Breasts, incidentally, are always referred to as "knockers", and sex as "leg-over".

Kershaw, the son of a headmaster, grew up in Rochdale, where the disappointment set in early, in spite of his genius (at the age of 51, he is still apt to boast about his A-level results, and the fact that, aged two, he could name all the allied generals in his father's history of the great war). The town was suffocatingly parochial, and the private school his parents forced him to attend was full of wankers (aka boys who liked football). Girls? On this score, his troubles were twofold: his height (small), plus their fondness for ELO. Nevertheless, in 1980 he managed to lose his virginity, to the sound – natch – of Van Morrison's Astral Weeks. He departed his economics A-level early to attend a Bob Dylan gig, but he still got – double natch – an "A", and was thus able to take up his place at the University of Leeds, where he read politics and, much more importantly, became entertainment secretary. The Clash, Motörhead, Haircut 100: he booked them all.

The rest – as Kershaw would surely tell you – is history. A stint at Radio Aire was followed by a period driving Billy Bragg around, and this by a job as a presenter of the Old Grey Whistle Test. When that old lady was axed, he went to Radio 1. People said he was John Peel's heir, but that wasn't how he saw it. In fact, he resented the implication that he did not have "musical tastes of my own". He certainly did. Andy, for instance, liked Bruce (Springsteen), an artist of whom Peel was "wilfully dismissive". I won't say much here about his embittered disquisitions on Peel. But I will note that when, in 2004, Peel dies of a heart attack on holiday in Peru, Kershaw's main feeling seems to be: I told you so. (Peel was too fat for high altitudes.)

His attitude to Peel is only matched, in narrative terms, by that towards his ex-partner, Juliette Banner, who is not even mentioned until page 309, though their relationship lasted 17 years. It was Kershaw's idea that they move to the Isle of Man, where they already owned a cottage (the better that he, a bike fanatic, might watch the TT races). But the dream turned sour on their first day, when she borrowed his mobile and discovered on it a message from a woman with whom he'd had a one-night stand at the Womad festival ("it alluded to leg-over in the Reading area"). What followed – Banner had to take out a restraining order against him; his refusal to abide by it led to three stretches in prison, and a period on the run – was miserable: for Kershaw, certainly, but even more so, surely, for his estranged family. Not that he has much sense of this. What strikes you all over again in the scant 30 pages he devotes to this time is his self-pity. No one is as unhappy as Andy. No one hurts as much.

Like many bullies and almost all drunks, Kershaw is nothing if not sentimental. In the war zones from where he occasionally reports for the BBC, he is action man. The piled bodies and human rights abuses seem to faze him not at all. But put on the Oldham Tinkers' "Come Whoam to Thi Childer an' Me", and the tears will flow, copious and unembarrassed.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Cleopatra: A Life by Stacy Schiff – review

By Vera Rule

Vera Rule guardian.co.uk, Friday 22 July 2011 22.55 BST

Cleopatra by Stacy Schiff

Luscious and scrupulous is a difficult combination to pull off, but Stacy Schiff does so in her life of Cleopatra. In addition, she has a tartness to match the standards of Cleo's handmaiden, Charmion (that's her exact name – Shakespeare bent it a bit, as he did everything else in the story), who stuck it to the Romans with her last breath. Schiff balances Ptolemaic forensics and Roman politics to conclude that Charmion's death, like that of Cleo and Iras – who did the pharaoh's hair and makeup for her sensational deathbed appearance – didn't depend on the unreliable nip of an asp. That legend was likely printed or promulgated by Cleo's enemy, Octavian. I've long wondered how this clever, indefatigable monarch, the richest ruler in the Mediterranean in her time, took on rather than up with Mark Antony, who was always a disaster waiting to happen (and who eventually did "happen" at Actium). Schiff makes sense of it: after Caesar's murder, he was simply the least worst risk to back, though only just. Poor lady.

By Vera Rule

Vera Rule guardian.co.uk, Friday 22 July 2011 22.55 BST

Cleopatra by Stacy Schiff

Luscious and scrupulous is a difficult combination to pull off, but Stacy Schiff does so in her life of Cleopatra. In addition, she has a tartness to match the standards of Cleo's handmaiden, Charmion (that's her exact name – Shakespeare bent it a bit, as he did everything else in the story), who stuck it to the Romans with her last breath. Schiff balances Ptolemaic forensics and Roman politics to conclude that Charmion's death, like that of Cleo and Iras – who did the pharaoh's hair and makeup for her sensational deathbed appearance – didn't depend on the unreliable nip of an asp. That legend was likely printed or promulgated by Cleo's enemy, Octavian. I've long wondered how this clever, indefatigable monarch, the richest ruler in the Mediterranean in her time, took on rather than up with Mark Antony, who was always a disaster waiting to happen (and who eventually did "happen" at Actium). Schiff makes sense of it: after Caesar's murder, he was simply the least worst risk to back, though only just. Poor lady.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Re: Biography and Autobiography

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-CxlmknIGEY&feature=relmfu

Mark Steel on Che Guevara 2/3

Mark Steel on Che Guevara 2/3

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Biography and Autobiography

Re: Biography and Autobiography

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ZAQLUbNiSk&feature=relmfu

Mark Steel on Che Guevara 3/3

Mark Steel on Che Guevara 3/3

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Page 2 of 2 •  1, 2

1, 2

Page 2 of 2

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum