The Great Sea

2 posters

Page 1 of 1

The Great Sea

The Great Sea

The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean by David Abulafia — review

This magnificent history shows how a narrow strip of sea became a meeting place of civilisations, writes Tom Holland

Tom Holland The Observer, Sunday 15 May 2011

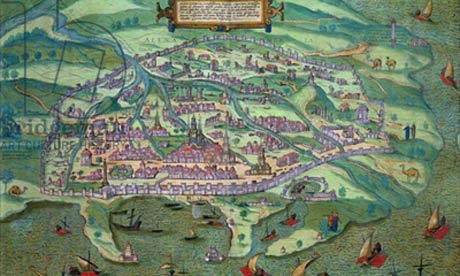

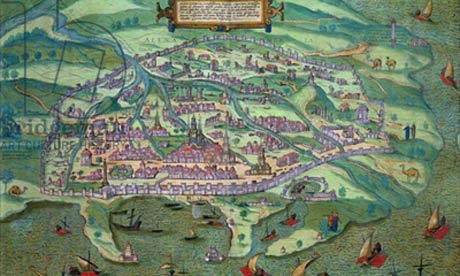

Map of Alexandria from the 'Civitates Orbis Terrarum' by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg in 1572. Photograph provided by Bridgeman Art

This summer, as Europeans sprawl on sunbeds in Málaga and bare their breasts in Faliraki, Libyans will be killing one another. The two halves of the Mediterranean will seem, even more than usual, entire worlds apart. Not wholly so, however. Tourists on Lampedusa – if they look out to sea from the beaches and nature reserves of that picturesque Italian island – may well see makeshift boats bobbing towards them, crammed to bursting with refugees from the turmoil in north Africa, a mere 70 miles away. The Mediterranean, as it has always done, serves to join as well as divide.

The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean by David Abulafia

Such is the paradox that provides David Abulafia, in his magnificent and quite stunningly compendious history of the Mediterranean, with a key to unlocking its rich and turbulent past. Wide enough to support radically distinctive civilisations, and yet narrow enough to ensure ready contact between them, the Mediterranean became, in Abulafia's opinion, "probably the most vigorous place of interaction between different societies on the face of this planet". A sweeping claim – but one more than backed up by a sensationally sweeping book. From the hominids who, as early as 130,000 BC, made their way from Africa to Crete bearing quartz hand axes, to the recent debt crisis in Greece, all of Mediterranean history is here.

Indeed, there is something almost eerie about the polymathic quality of Abulafia's knowledge. Midway through his book, he touches on the career of a medieval namesake of his, a Jewish intellectual from Saragossa who, in addition to the Kabbalah, had also studied Christian and Muslim mysticism, and who had "travelled the Mediterranean from end to end".

The Great Sea is a 21st-century echoing of this startling career. The various faiths and civilisations that have flourished on the shores of the Mediterranean are treated with a commendable even-handedness – and if Abulafia neglects some regions at the expense of others, this i s not due to any prejudice on his part. Only late in his book, for instance, with the onset of the Napoleonic wars, does he finally permit Corsica to make a fleeting appearance – but Abulafia sees no reason to apologise for this. "The island has not featured in this book as often as Sardinia, Mallorca, Crete or Cyprus," he explains, "simply because it offered fewer facilities for trans-Mediterreanean shipping, and fewer products of its own than the other islands." This is a history in which even omissions make a point.

And ultimately, just as the absence of Corsica is predetermined by geography, so too is the starring role of the islands and waters that extend between the toe of Italy and the coast of Tunisia. Again and again, it is this stretch of the Mediterranean that provides the pivot on which Abulafia's narrative turns. If Corsica ranks as the mousy understudy among his cast of islands, Sicily is the undoubted star: a prize so rich and so central that it constituted, until its relative pauperisation in the 18th century, the most precious real estate in the entire Mediterranean.

Precious too, however, were the shipping lanes which linked the western to the eastern half of the sea, and which hosted, on or above the waters now crowded with refugees from north Africa, any number of decisive battles. It was off Sicily that Carthaginian sea power was broken for ever by the upstart navies of Rome, that the Ottomans were repulsed by the Knights of St John, and that the Axis air forces beat themselves fruitlessly against the defiant rock of Malta. Contained as all these clashes are within the same epic sweep of history, they come to seem, not discordant episodes separated by stupefying reaches of time, but rather badges of war hanging from a single string.

All of which suggests that Abulafia, despite his claim to have written "a human history of the Mediterranean", is not, perhaps, so very far in his conclusions from those of Fernand Braudel, the great French Annaliste whose own history of the Mediterranean stands in an almost Oedipal relationship to Abulafia's. Braudel famously dismissed events as mere "surface disturbances, crests of foam that the tides of history carry on their strong backs": an assertion that seems to have riled Abulafia so much that he has given us 650 pages positively overflowing with events. These include the origins of pesto as well as the outbreak of the Punic wars, and the spread of chewing gum no less than the rise of Venice.

Such events stand revealed, in Abulafia's masterly narrative, as very much more than froth. Few after reading The Great Sea would doubt the truth of its animating claim, that "the human hand has been more important in moulding the history | of the Mediterranean than Braudel was ever prepared to admit".

Yet Abulafia, by providing such an all-encompassing survey of the Mediterranean's past, has demonstrated as well just how remorseless, over the millennia, has been the influence upon all its many varied civilisations of geography. Far from vanquishing Braudel's bleak determinism, Abulafia's book seems, at its profoundest, only to confirm it.

Tom Holland's most recent book is Millennium: The End of the World and the Forging of Christendom.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

This magnificent history shows how a narrow strip of sea became a meeting place of civilisations, writes Tom Holland

Tom Holland The Observer, Sunday 15 May 2011

Map of Alexandria from the 'Civitates Orbis Terrarum' by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg in 1572. Photograph provided by Bridgeman Art

This summer, as Europeans sprawl on sunbeds in Málaga and bare their breasts in Faliraki, Libyans will be killing one another. The two halves of the Mediterranean will seem, even more than usual, entire worlds apart. Not wholly so, however. Tourists on Lampedusa – if they look out to sea from the beaches and nature reserves of that picturesque Italian island – may well see makeshift boats bobbing towards them, crammed to bursting with refugees from the turmoil in north Africa, a mere 70 miles away. The Mediterranean, as it has always done, serves to join as well as divide.

The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean by David Abulafia

Such is the paradox that provides David Abulafia, in his magnificent and quite stunningly compendious history of the Mediterranean, with a key to unlocking its rich and turbulent past. Wide enough to support radically distinctive civilisations, and yet narrow enough to ensure ready contact between them, the Mediterranean became, in Abulafia's opinion, "probably the most vigorous place of interaction between different societies on the face of this planet". A sweeping claim – but one more than backed up by a sensationally sweeping book. From the hominids who, as early as 130,000 BC, made their way from Africa to Crete bearing quartz hand axes, to the recent debt crisis in Greece, all of Mediterranean history is here.

Indeed, there is something almost eerie about the polymathic quality of Abulafia's knowledge. Midway through his book, he touches on the career of a medieval namesake of his, a Jewish intellectual from Saragossa who, in addition to the Kabbalah, had also studied Christian and Muslim mysticism, and who had "travelled the Mediterranean from end to end".

The Great Sea is a 21st-century echoing of this startling career. The various faiths and civilisations that have flourished on the shores of the Mediterranean are treated with a commendable even-handedness – and if Abulafia neglects some regions at the expense of others, this i s not due to any prejudice on his part. Only late in his book, for instance, with the onset of the Napoleonic wars, does he finally permit Corsica to make a fleeting appearance – but Abulafia sees no reason to apologise for this. "The island has not featured in this book as often as Sardinia, Mallorca, Crete or Cyprus," he explains, "simply because it offered fewer facilities for trans-Mediterreanean shipping, and fewer products of its own than the other islands." This is a history in which even omissions make a point.

And ultimately, just as the absence of Corsica is predetermined by geography, so too is the starring role of the islands and waters that extend between the toe of Italy and the coast of Tunisia. Again and again, it is this stretch of the Mediterranean that provides the pivot on which Abulafia's narrative turns. If Corsica ranks as the mousy understudy among his cast of islands, Sicily is the undoubted star: a prize so rich and so central that it constituted, until its relative pauperisation in the 18th century, the most precious real estate in the entire Mediterranean.

Precious too, however, were the shipping lanes which linked the western to the eastern half of the sea, and which hosted, on or above the waters now crowded with refugees from north Africa, any number of decisive battles. It was off Sicily that Carthaginian sea power was broken for ever by the upstart navies of Rome, that the Ottomans were repulsed by the Knights of St John, and that the Axis air forces beat themselves fruitlessly against the defiant rock of Malta. Contained as all these clashes are within the same epic sweep of history, they come to seem, not discordant episodes separated by stupefying reaches of time, but rather badges of war hanging from a single string.

All of which suggests that Abulafia, despite his claim to have written "a human history of the Mediterranean", is not, perhaps, so very far in his conclusions from those of Fernand Braudel, the great French Annaliste whose own history of the Mediterranean stands in an almost Oedipal relationship to Abulafia's. Braudel famously dismissed events as mere "surface disturbances, crests of foam that the tides of history carry on their strong backs": an assertion that seems to have riled Abulafia so much that he has given us 650 pages positively overflowing with events. These include the origins of pesto as well as the outbreak of the Punic wars, and the spread of chewing gum no less than the rise of Venice.

Such events stand revealed, in Abulafia's masterly narrative, as very much more than froth. Few after reading The Great Sea would doubt the truth of its animating claim, that "the human hand has been more important in moulding the history | of the Mediterranean than Braudel was ever prepared to admit".

Yet Abulafia, by providing such an all-encompassing survey of the Mediterranean's past, has demonstrated as well just how remorseless, over the millennia, has been the influence upon all its many varied civilisations of geography. Far from vanquishing Braudel's bleak determinism, Abulafia's book seems, at its profoundest, only to confirm it.

Tom Holland's most recent book is Millennium: The End of the World and the Forging of Christendom.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Last edited by eddie on Sat Jul 23, 2011 3:31 pm; edited 1 time in total

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Great Sea

Re: The Great Sea

The Great Sea by David Abulafia – review

David Abulafia's history of the Mediterranean takes in ancient empires and modern tourists

Tim Whitmarsh guardian.co.uk, Friday 17 June 2011 23.55 BST

Looking out to sea ... Abulafia seems to admire most the pioneering sailors of the pre-industrial age. Photograph: Rene Mattes/Hemis/Corbis

The Hereford mappa mundi, created around 1300, was the medieval world's most sophisticated attempt to represent the planet as it was known at the time. It was, however, designed not for geographical precision but as a statement of ideology, expressing a contrast between the centre of the world, civilised and ordered, and the untamed, fabulous peripheries. Dead centre sits Jerusalem, marked (rather optimistically, since it was at the time under Mamluk rule) with an eye-catching cross. This was an eminently Christian vision of the world, as the appearance at the map's apex of a benignly presiding Christ clearly signals.

The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean by David Abulafia

The map's Christianity, however, is in one sense just a veneer. Medieval maps were based on now-lost Roman antecedents, which had Rome at the centre. The recalibration, shifting from Rome to Jerusalem, required only the slightest manipulation of what was already a more imaginative than realistic depiction of geography, but it was an eloquent token of both the changes and the continuity between antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Empires rise and fall, great cities wax and wane; but for the west at any rate, the major constant from antiquity to at least the 16th century was the sea whose name even now pronounces it the centre (Latin medius) of the world (terra). Take a step back from the mappa mundi, and the wash of green ink at the heart of the vellum tells you all you need to know about this mighty sea's enduring dominance in the imagination of the pre-modern world.

It was the development of reliable marine shipping, probably by the Cretan Minoans early in the second millennium BC, that allowed for the Mediterranean's centrality to the western world. The great Asian and African civilisations of the early bronze age had been largely confined to the alluvial river valleys created in the wake of the ice age: the Indus, the Yellow river and Yangtze, the Euphrates and Tigris, the Nile. Over time shipping created a huge international network of trade in grain, minerals, wood and goods that extended from Syria to Cadiz. One crucial effect of this was to give a new power to the strategically located sites in the sea's centre: the islands of Crete and Sicily, the Greek and Italian peninsulae, and Carthage (in modern Tunisia) were well placed to control these networks. The world as it appeared to English mapmakers in 1300, culturally dominated by the classical past and Latin Christianity, was taking shape.

David Abulafia offers an ambitious and breathtakingly learned account of the journey to centrality of "the great sea", from 22,000BC to the present day. He is far from the first Mediterranean historian, and marine history has now achieved a central role in the academy – behind it is a desire to move beyond the nationalism of land-based history, and to explore instead the transience and fluidity of humanity.

What is distinctive about this book is that it offers, as the subtitle puts it, a "human history". There is very little here about Mediterranean ecology, which has loomed large in previous accounts. And although not short of conventional narrative – ancient empires, ambitious medieval city states, modern nations, the lingering end of colonialism, the arrival of refugees and tourists – this is first and foremost a story about trade. Abulafia seems to admire most the pioneering sailors of the pre-industrial age who risked their lives for profit or curiosity, whether Greeks, Phoenicians, Genoese, Pisans, Jews, Muslims or Turks. (These traders, however, had sinister doubles in the pirates and corsairs who are equally preponderant in these pages.) History's usual roll-call of tyrants and plutocrats are here, but alongside them are men (and they are almost always men) of modest means, shaping the world as we know it by accident rather than design.

In spite of this admirable pluralism, however, a Mediterranean-centred view of history can slide into eurocentrism; for while the cities of the "European" coasts have always been orientated primarily towards the sea, their eastern and southern counterparts have also faced inland towards Asia, Africa and Arabia. Readers will learn nothing, for example, of the overland routes that connected ancient Syro-Palestine to Mesopotamia and Arabia, and hence will miss the central cultural contribution of the middle east not only to the eastern seaboard but also thereby to Greek mythology, and hence to the western tradition as a whole. Mecca, so central to the lives of the millions of Mediterranean Muslims, remains always out-of-shot (in notable contrast to Jerusalem). And despite its immense significance for the region, Ottoman history cannot be comfortably accommodated into a Mediterranean framework.

Perhaps it is the fate of all histories to be judged as much by what they omit as what they include. But this should not cloud Abulafia's achievement: The Great Sea is a deeply impressive book.

Tim Whitmarsh's Narrative and Identity in the Ancient Greek Novel is published by Cambridge.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

David Abulafia's history of the Mediterranean takes in ancient empires and modern tourists

Tim Whitmarsh guardian.co.uk, Friday 17 June 2011 23.55 BST

Looking out to sea ... Abulafia seems to admire most the pioneering sailors of the pre-industrial age. Photograph: Rene Mattes/Hemis/Corbis

The Hereford mappa mundi, created around 1300, was the medieval world's most sophisticated attempt to represent the planet as it was known at the time. It was, however, designed not for geographical precision but as a statement of ideology, expressing a contrast between the centre of the world, civilised and ordered, and the untamed, fabulous peripheries. Dead centre sits Jerusalem, marked (rather optimistically, since it was at the time under Mamluk rule) with an eye-catching cross. This was an eminently Christian vision of the world, as the appearance at the map's apex of a benignly presiding Christ clearly signals.

The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean by David Abulafia

The map's Christianity, however, is in one sense just a veneer. Medieval maps were based on now-lost Roman antecedents, which had Rome at the centre. The recalibration, shifting from Rome to Jerusalem, required only the slightest manipulation of what was already a more imaginative than realistic depiction of geography, but it was an eloquent token of both the changes and the continuity between antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Empires rise and fall, great cities wax and wane; but for the west at any rate, the major constant from antiquity to at least the 16th century was the sea whose name even now pronounces it the centre (Latin medius) of the world (terra). Take a step back from the mappa mundi, and the wash of green ink at the heart of the vellum tells you all you need to know about this mighty sea's enduring dominance in the imagination of the pre-modern world.

It was the development of reliable marine shipping, probably by the Cretan Minoans early in the second millennium BC, that allowed for the Mediterranean's centrality to the western world. The great Asian and African civilisations of the early bronze age had been largely confined to the alluvial river valleys created in the wake of the ice age: the Indus, the Yellow river and Yangtze, the Euphrates and Tigris, the Nile. Over time shipping created a huge international network of trade in grain, minerals, wood and goods that extended from Syria to Cadiz. One crucial effect of this was to give a new power to the strategically located sites in the sea's centre: the islands of Crete and Sicily, the Greek and Italian peninsulae, and Carthage (in modern Tunisia) were well placed to control these networks. The world as it appeared to English mapmakers in 1300, culturally dominated by the classical past and Latin Christianity, was taking shape.

David Abulafia offers an ambitious and breathtakingly learned account of the journey to centrality of "the great sea", from 22,000BC to the present day. He is far from the first Mediterranean historian, and marine history has now achieved a central role in the academy – behind it is a desire to move beyond the nationalism of land-based history, and to explore instead the transience and fluidity of humanity.

What is distinctive about this book is that it offers, as the subtitle puts it, a "human history". There is very little here about Mediterranean ecology, which has loomed large in previous accounts. And although not short of conventional narrative – ancient empires, ambitious medieval city states, modern nations, the lingering end of colonialism, the arrival of refugees and tourists – this is first and foremost a story about trade. Abulafia seems to admire most the pioneering sailors of the pre-industrial age who risked their lives for profit or curiosity, whether Greeks, Phoenicians, Genoese, Pisans, Jews, Muslims or Turks. (These traders, however, had sinister doubles in the pirates and corsairs who are equally preponderant in these pages.) History's usual roll-call of tyrants and plutocrats are here, but alongside them are men (and they are almost always men) of modest means, shaping the world as we know it by accident rather than design.

In spite of this admirable pluralism, however, a Mediterranean-centred view of history can slide into eurocentrism; for while the cities of the "European" coasts have always been orientated primarily towards the sea, their eastern and southern counterparts have also faced inland towards Asia, Africa and Arabia. Readers will learn nothing, for example, of the overland routes that connected ancient Syro-Palestine to Mesopotamia and Arabia, and hence will miss the central cultural contribution of the middle east not only to the eastern seaboard but also thereby to Greek mythology, and hence to the western tradition as a whole. Mecca, so central to the lives of the millions of Mediterranean Muslims, remains always out-of-shot (in notable contrast to Jerusalem). And despite its immense significance for the region, Ottoman history cannot be comfortably accommodated into a Mediterranean framework.

Perhaps it is the fate of all histories to be judged as much by what they omit as what they include. But this should not cloud Abulafia's achievement: The Great Sea is a deeply impressive book.

Tim Whitmarsh's Narrative and Identity in the Ancient Greek Novel is published by Cambridge.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Great Sea

Re: The Great Sea

Constance

You're a big Simon Winchester fan, so this might interest you:

**********************************************************************************

Atlantic: A Vast Ocean of a Million Stories, by Simon Winchester – review

By Ian Pindar

Ian Pindar guardian.co.uk, Friday 22 July 2011 22.55 BST

Atlantic: A Vast Ocean of a Million Stories: The Biography of an Ocean by Simon Winchester

The Atlantic is "a living thing", declares Simon Winchester, "forever roaring, thundering, boiling, crashing, swelling, lapping" – so it's a shame we no longer treat it with the same "awed respect" as our ancestors did. This mighty arena of trade and war is, he argues, as important to our modern world as the Mediterranean was to the Greeks and Romans, but an era of cheap transatlantic flight has reduced it to "the pond". Here, in this polluted and overfished ocean, is our despoliation of the natural world in microcosm. Winchester's ruminative prose is capable of keeping any amount of Atlantic trivia afloat, from memories of crossing it by liner in 1963 to the horrors of the slave trade, from the Anglo-Saxon poem "The Seafarer" to Churchill and Roosevelt meeting at sea to discuss the Atlantic Charter. Later, Winchester strikes a more sombre, admonitory note, meditating on the melting ice caps and the impact of climate change on coastal cities, and finally imagining the death of this "grey-green vastness" in "about 170 million years".

You're a big Simon Winchester fan, so this might interest you:

**********************************************************************************

Atlantic: A Vast Ocean of a Million Stories, by Simon Winchester – review

By Ian Pindar

Ian Pindar guardian.co.uk, Friday 22 July 2011 22.55 BST

Atlantic: A Vast Ocean of a Million Stories: The Biography of an Ocean by Simon Winchester

The Atlantic is "a living thing", declares Simon Winchester, "forever roaring, thundering, boiling, crashing, swelling, lapping" – so it's a shame we no longer treat it with the same "awed respect" as our ancestors did. This mighty arena of trade and war is, he argues, as important to our modern world as the Mediterranean was to the Greeks and Romans, but an era of cheap transatlantic flight has reduced it to "the pond". Here, in this polluted and overfished ocean, is our despoliation of the natural world in microcosm. Winchester's ruminative prose is capable of keeping any amount of Atlantic trivia afloat, from memories of crossing it by liner in 1963 to the horrors of the slave trade, from the Anglo-Saxon poem "The Seafarer" to Churchill and Roosevelt meeting at sea to discuss the Atlantic Charter. Later, Winchester strikes a more sombre, admonitory note, meditating on the melting ice caps and the impact of climate change on coastal cities, and finally imagining the death of this "grey-green vastness" in "about 170 million years".

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Great Sea

Re: The Great Sea

The Great Sea by David Abulafia – review

A fascinating study of the Mediterranean is full of stories pulled from the flotsam and jetsam of the past

Nicholas Lezard

guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 1 May 2012 13.55 BST

Drop in the ocean … boys dive into the Mediterranean from Cleopatra's Rock, on the Egyptian coast 500km north of Cairo. Photograph: Khaled El Fiqi/EPA

I didn't know this: in 1794, the Corsican parliament voted for union with Great Britain, to be "a self-governing community under the sovereign authority of King George III. The Corsicans were granted their own flag, carrying a moor's head alongside the royal arms, as well as a motto: Amici e non di ventura, 'friends and not by chance'." The union lasted two years.

The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean

by David Abulafia

That Abulafia finds room for such an episode in a book of such ambitious scope shows how impressive his achievement is. To give you some idea: even though, perforce, historians attempting this kind of thing are obliged to give disproportionate space to recent history, we are still only starting on 1350 halfway through this book (pushing 800 pages, with notes).

And it is a wonderful idea for a book. The Mediterranean is a kind of traversable void that has been, for millennia, a space around which humans have been able to travel. It is both negative – you can't grow things on it, or build on it – and positive: you can use it to get to somewhere else, to take things there and bring other things back. Under "things" you may also include "ideas". I've sailed, over the years, round large stretches of it, and have everywhere been struck by the similarity of coastal cultures in every harbour and port I've seen. The religions and lifestyles of the inhabitants further inland may be different, but the pale blue of the fishing-boats; the eyes painted on the prows of the smaller vessels; the smell of frying sardines everywhere – these are constants, and I suspect that they have been so since antiquity.

That said, Abulafia warns us, in his conclusion, against searching for a "fundamental unity" of Mediterranean identity, and to "note diversity" instead. And there is indeed that, as the northern and western fringes of the sea guard themselves with increasing rigour against those wishing to move there from the southern fringes. The last picture in the book is of a small boatful of would-be African immigrants trying to land somewhere near Gibraltar. (And the plate above that shows a pullulating mass of humanity, not looking terribly diverse at all, sunbathing at Lloret de Mar in Catalonia, which I am old enough to remember as a quaint little resort.)

I had, at first, cocked an eyebrow at the book's subtitle – surely the word "human" is redundant? (I suppose a donkey's history of the Med could make for interesting, if unrelievedly grim, reading.) But it is full of stories that Abulafia has pulled from the flotsam and jetsam of history. Archaeologists sorting through the remains of an Etruscan settlement on the mouth of the Po found some artwork so bad that the anonymous pseudo-Attic artist has been given the name "the Worst Painter". The first Neanderthal bones were actually found much earlier than the ones in the Neander Valley; "Neanderthal Man" should really be called "Gibraltar Woman". Wenamum, an emissary from Karnak in Pharaonic Egypt, c1000BC, noted that the chief of Byblos, where he had gone to pick up timber, told him to "get out of my harbour!" every day for a month; but as he had kept other emissaries out for 17 years, he shouldn't complain. Herodotus tells us that Lydians invented board games (but not draughts) to keep their minds off hunger during a famine. A Christian request to Roger I, Norman count of Sicily in the 11th century, to move against the Tunisian port of Mahdia, was met by Roger lifting up his thigh and letting out "a great fart". The envoys of Dionysios the tyrant were mocked at the 384BC Olympic Games because he was – well, a tyrant (would that we had the balls to do the same today). The marble female head from Keros in the Cycladic islands, from the first half of the third millennium BC, is the most astonishingly beautiful piece of sculpture you will ever see, and makes every sculpture made afterwards seem redundantly and vulgarly over-detailed.

And so on. There is so much here that you risk brain overload. This is your must-take holiday read for the summer. Remember the cry of Xenophon's 10,000: "Thálatta! Thálatta!" – the sea, the sea!

A fascinating study of the Mediterranean is full of stories pulled from the flotsam and jetsam of the past

Nicholas Lezard

guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 1 May 2012 13.55 BST

Drop in the ocean … boys dive into the Mediterranean from Cleopatra's Rock, on the Egyptian coast 500km north of Cairo. Photograph: Khaled El Fiqi/EPA

I didn't know this: in 1794, the Corsican parliament voted for union with Great Britain, to be "a self-governing community under the sovereign authority of King George III. The Corsicans were granted their own flag, carrying a moor's head alongside the royal arms, as well as a motto: Amici e non di ventura, 'friends and not by chance'." The union lasted two years.

The Great Sea: A Human History of the Mediterranean

by David Abulafia

That Abulafia finds room for such an episode in a book of such ambitious scope shows how impressive his achievement is. To give you some idea: even though, perforce, historians attempting this kind of thing are obliged to give disproportionate space to recent history, we are still only starting on 1350 halfway through this book (pushing 800 pages, with notes).

And it is a wonderful idea for a book. The Mediterranean is a kind of traversable void that has been, for millennia, a space around which humans have been able to travel. It is both negative – you can't grow things on it, or build on it – and positive: you can use it to get to somewhere else, to take things there and bring other things back. Under "things" you may also include "ideas". I've sailed, over the years, round large stretches of it, and have everywhere been struck by the similarity of coastal cultures in every harbour and port I've seen. The religions and lifestyles of the inhabitants further inland may be different, but the pale blue of the fishing-boats; the eyes painted on the prows of the smaller vessels; the smell of frying sardines everywhere – these are constants, and I suspect that they have been so since antiquity.

That said, Abulafia warns us, in his conclusion, against searching for a "fundamental unity" of Mediterranean identity, and to "note diversity" instead. And there is indeed that, as the northern and western fringes of the sea guard themselves with increasing rigour against those wishing to move there from the southern fringes. The last picture in the book is of a small boatful of would-be African immigrants trying to land somewhere near Gibraltar. (And the plate above that shows a pullulating mass of humanity, not looking terribly diverse at all, sunbathing at Lloret de Mar in Catalonia, which I am old enough to remember as a quaint little resort.)

I had, at first, cocked an eyebrow at the book's subtitle – surely the word "human" is redundant? (I suppose a donkey's history of the Med could make for interesting, if unrelievedly grim, reading.) But it is full of stories that Abulafia has pulled from the flotsam and jetsam of history. Archaeologists sorting through the remains of an Etruscan settlement on the mouth of the Po found some artwork so bad that the anonymous pseudo-Attic artist has been given the name "the Worst Painter". The first Neanderthal bones were actually found much earlier than the ones in the Neander Valley; "Neanderthal Man" should really be called "Gibraltar Woman". Wenamum, an emissary from Karnak in Pharaonic Egypt, c1000BC, noted that the chief of Byblos, where he had gone to pick up timber, told him to "get out of my harbour!" every day for a month; but as he had kept other emissaries out for 17 years, he shouldn't complain. Herodotus tells us that Lydians invented board games (but not draughts) to keep their minds off hunger during a famine. A Christian request to Roger I, Norman count of Sicily in the 11th century, to move against the Tunisian port of Mahdia, was met by Roger lifting up his thigh and letting out "a great fart". The envoys of Dionysios the tyrant were mocked at the 384BC Olympic Games because he was – well, a tyrant (would that we had the balls to do the same today). The marble female head from Keros in the Cycladic islands, from the first half of the third millennium BC, is the most astonishingly beautiful piece of sculpture you will ever see, and makes every sculpture made afterwards seem redundantly and vulgarly over-detailed.

And so on. There is so much here that you risk brain overload. This is your must-take holiday read for the summer. Remember the cry of Xenophon's 10,000: "Thálatta! Thálatta!" – the sea, the sea!

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Great Sea

Re: The Great Sea

Thank you for remembering, Ed.

Yes, I read it a few months ago.

He talks about the depletion of cod in the north Atlantic. Very sad, and scary.

Yes, I read it a few months ago.

He talks about the depletion of cod in the north Atlantic. Very sad, and scary.

eddie wrote:Constance

You're a big Simon Winchester fan, so this might interest you:

**********************************************************************************

Atlantic: A Vast Ocean of a Million Stories, by Simon Winchester – review

By Ian Pindar

Ian Pindar guardian.co.uk, Friday 22 July 2011 22.55 BST

Atlantic: A Vast Ocean of a Million Stories: The Biography of an Ocean by Simon Winchester

The Atlantic is "a living thing", declares Simon Winchester, "forever roaring, thundering, boiling, crashing, swelling, lapping" – so it's a shame we no longer treat it with the same "awed respect" as our ancestors did. This mighty arena of trade and war is, he argues, as important to our modern world as the Mediterranean was to the Greeks and Romans, but an era of cheap transatlantic flight has reduced it to "the pond". Here, in this polluted and overfished ocean, is our despoliation of the natural world in microcosm. Winchester's ruminative prose is capable of keeping any amount of Atlantic trivia afloat, from memories of crossing it by liner in 1963 to the horrors of the slave trade, from the Anglo-Saxon poem "The Seafarer" to Churchill and Roosevelt meeting at sea to discuss the Atlantic Charter. Later, Winchester strikes a more sombre, admonitory note, meditating on the melting ice caps and the impact of climate change on coastal cities, and finally imagining the death of this "grey-green vastness" in "about 170 million years".

Constance- Posts : 500

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 67

Location : New York City

Similar topics

Similar topics» Great monologues

» Great cathedrals of the world

» Truly great moments in sport

» {*) Download Es kommt ein Tag Movie Great Quality ['mightyupload']

» {*^ Watch The Great Mouse Detective Online - tvDuck.com [*thevideo*]

» Great cathedrals of the world

» Truly great moments in sport

» {*) Download Es kommt ein Tag Movie Great Quality ['mightyupload']

» {*^ Watch The Great Mouse Detective Online - tvDuck.com [*thevideo*]

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum