Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh

Page 1 of 1

Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh

Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh

Skagboys by Irvine Welsh – review

Despite some fine moments, Irvine Welsh's prequel to his blockbuster Trainspotting misses the mark

Bella Bathurst

The Observer, Sunday 15 April 2012

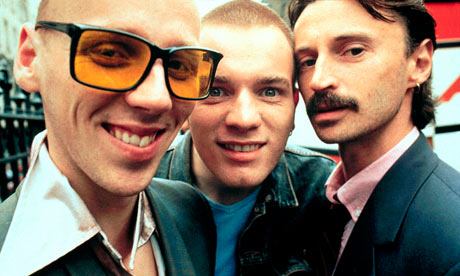

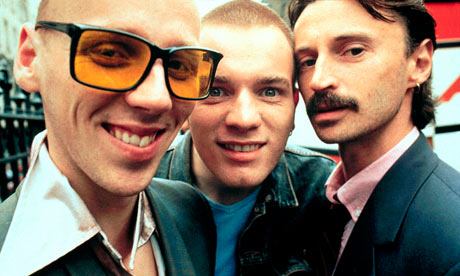

Ewen Bremner, Ewan McGregor and Robert Carlyle in Danny Boyle's 1996 adaptation of Trainspotting. Photograph: Sportsphoto/ Allstar/ Cinetext Collection

A long long time ago, back in the early 1990s, there were only three novels about Edinburgh. There was Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde (which wasn't actually set in Edinburgh at all), there was James Hogg's Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner and more recently Muriel Spark's The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. The Scottish capital had plenty of other books to its name but those were the only three that mattered, the ones that knocked through all of Edinburgh's lovely false fronts to the far more interesting things behind.

Skagboys

by Irvine Welsh

Forty miles away, there were writers falling over themselves to talk about Glasgow: James Kelman, Alasdair Gray, Jeff Torrington, AL Kennedy, Janice Galloway. Somehow, Edinburgh's great rival just offered more to describe – more people, more history, fewer layers to scrape off between appearance and truth. Glasgow was cool, and whatever Edinburgh was – beautiful, vertiginous, cold – it had never in its whole life been cool.

And then in 1993, a book called Trainspotting was published by an unknown council worker called Irvine Welsh. Trainspotting told the story of another Edinburgh entirely; not the pretty neoclassical bit in the middle, but the schemes and estates beyond the invisible Pale – places like Saughton and Niddrie and Sighthill which had been used by the Tories to test out contentious new ideas: closing the car plants, bringing in the poll tax, flooding the neighbourhoods with cheap high-grade heroin… By the time Trainspotting came out, Edinburgh had stopped being the Athens of the North and become instead the Aids capital of Europe.

If Welsh had set his novel in Glasgow, there would have been a brief fight about swearwords and then silence. Because he set it in Edinburgh, Trainspotting went off like a detonation. It was written in a thick Leith accent and it told the stories of a bunch of neds and schemies on the hunt for dole, sex and junk. But Trainspotting's real brilliance was the zest and joy and sheer black-hearted energy of its writing. Now, nearly 20 years later, it's difficult to imagine Scotland without the psychopathic Begbie or Bond-obsessed Sick Boy, or Renton's echoing lament: "Some hate the English. I don't. They're just wankers. We, on the other hand, are colonised by wankers…"

Britain loved Trainspotting, Scotland loved the spectacle of Edinburgh with its knickers off, and the city itself remained ambivalent. On the one hand, the revelation that it had as many issues with sectarianism and STDs as the wild wet west irritated the New Town enormously; even now, the official Edinburgh Unesco City of Literature website pays Trainspotting the great compliment of completely ignoring it. On the other, most people soon realised that Welsh had somehow pulled off the trick of conveying a pungent anti-drugs message while simultaneously making Edinburgh look interesting. Suddenly the place was full of Fettes boys hanging out at the Foot of the Walk and talking radge with their swedgin and barry.

Anyway. All that said, what exactly is the point of Skagboys? Welsh can never be unknown again. His writing can never shock like it once did. No prequel or sequel can have the impact of Trainspotting. Ecstasy – his 1996 follow-up – didn't exactly tank, but nor did it reach anywhere near Trainspotting's giddy heights.

And first impressions aren't great. Skagboys is long: 548 pages in hardback. There are a lot of characters and too many voices. Sometimes, when Welsh slips back from Edinburgh to English – as he does with Renton's parents – the deficiencies in his fiction become obvious. Worst of all, there are signs that he's using Skagboys as a teaching aid. Brief socio-historical pass notes are included every couple of chapters for the benefit of anyone too young, too posh or too English to have noticed what was happening to Scotland during the 1980s. Optimum laboratory conditions, in other words, for a disastrous read.

Except that Skagboys isn't. We start out back in the days when Mark Renton is clean and reading for joint honours at Aberdeen Uni. He and Sick Boy take their first fix. Renton's brother Wee Davie dies. The heroin begins to take hold. His family begin to disintegrate and the good girls fall away. He drops out of university and goes to work on the boats. "Schopenhauer was right," Renton thinks: "life has tae be aboot disillusionment; stumbling inexorably towards the totally fucked."

For anyone who loved Trainspotting first time around there's something deeply cheering about returning to Welsh's world. "Are you sexually active?'' asks the woman at the Aids clinic. "Usually, aye, Keezbo goes, no gittin her at aw – but sometimes ah jist like tae lie back wi a bird oan top…"

For those who want to be shocked, there's plenty of provocation – Renton tossing off his "spasticated" brother, puppies down rubbish chutes munching on aborted foetuses, a memorable incident involving budgies and a mastectomy – and plenty of perfect moments: Renton torn by "resentment and tenderness" beside his grieving parents, Begbie raging at others for admiring his singing voice, Renton and Sick Boy wound round each other like bindweed.

And many of Welsh's wider points are well made. His "Notes on an Epidemic" include a couple of monthly lists of reported HIV-positive cases: 39 names, each with their terrible case histories summed up in a sentence. "If being Scottish is about one thing, it's aboot gittin fucked up," Renton explains. "Tae us intoxication isnae just a huge laugh or even a basic human right. It's a way ay life, a political philosophy."

And then things go slack and you can sense Welsh's concentration wandering. Twenty years later, he's too far from a world he was already distanced from when Trainspotting came out. Besides, part of the problem of writing about drugs is that almost by definition, every fix gets a little less interesting: heroin, like happiness, starts to write white. For hardcore enthusiasts, Skagboys' more measured pace and broad overview is a treat. For everyone else Trainspotting said it all, and said it better.

Despite some fine moments, Irvine Welsh's prequel to his blockbuster Trainspotting misses the mark

Bella Bathurst

The Observer, Sunday 15 April 2012

Ewen Bremner, Ewan McGregor and Robert Carlyle in Danny Boyle's 1996 adaptation of Trainspotting. Photograph: Sportsphoto/ Allstar/ Cinetext Collection

A long long time ago, back in the early 1990s, there were only three novels about Edinburgh. There was Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde (which wasn't actually set in Edinburgh at all), there was James Hogg's Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner and more recently Muriel Spark's The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. The Scottish capital had plenty of other books to its name but those were the only three that mattered, the ones that knocked through all of Edinburgh's lovely false fronts to the far more interesting things behind.

Skagboys

by Irvine Welsh

Forty miles away, there were writers falling over themselves to talk about Glasgow: James Kelman, Alasdair Gray, Jeff Torrington, AL Kennedy, Janice Galloway. Somehow, Edinburgh's great rival just offered more to describe – more people, more history, fewer layers to scrape off between appearance and truth. Glasgow was cool, and whatever Edinburgh was – beautiful, vertiginous, cold – it had never in its whole life been cool.

And then in 1993, a book called Trainspotting was published by an unknown council worker called Irvine Welsh. Trainspotting told the story of another Edinburgh entirely; not the pretty neoclassical bit in the middle, but the schemes and estates beyond the invisible Pale – places like Saughton and Niddrie and Sighthill which had been used by the Tories to test out contentious new ideas: closing the car plants, bringing in the poll tax, flooding the neighbourhoods with cheap high-grade heroin… By the time Trainspotting came out, Edinburgh had stopped being the Athens of the North and become instead the Aids capital of Europe.

If Welsh had set his novel in Glasgow, there would have been a brief fight about swearwords and then silence. Because he set it in Edinburgh, Trainspotting went off like a detonation. It was written in a thick Leith accent and it told the stories of a bunch of neds and schemies on the hunt for dole, sex and junk. But Trainspotting's real brilliance was the zest and joy and sheer black-hearted energy of its writing. Now, nearly 20 years later, it's difficult to imagine Scotland without the psychopathic Begbie or Bond-obsessed Sick Boy, or Renton's echoing lament: "Some hate the English. I don't. They're just wankers. We, on the other hand, are colonised by wankers…"

Britain loved Trainspotting, Scotland loved the spectacle of Edinburgh with its knickers off, and the city itself remained ambivalent. On the one hand, the revelation that it had as many issues with sectarianism and STDs as the wild wet west irritated the New Town enormously; even now, the official Edinburgh Unesco City of Literature website pays Trainspotting the great compliment of completely ignoring it. On the other, most people soon realised that Welsh had somehow pulled off the trick of conveying a pungent anti-drugs message while simultaneously making Edinburgh look interesting. Suddenly the place was full of Fettes boys hanging out at the Foot of the Walk and talking radge with their swedgin and barry.

Anyway. All that said, what exactly is the point of Skagboys? Welsh can never be unknown again. His writing can never shock like it once did. No prequel or sequel can have the impact of Trainspotting. Ecstasy – his 1996 follow-up – didn't exactly tank, but nor did it reach anywhere near Trainspotting's giddy heights.

And first impressions aren't great. Skagboys is long: 548 pages in hardback. There are a lot of characters and too many voices. Sometimes, when Welsh slips back from Edinburgh to English – as he does with Renton's parents – the deficiencies in his fiction become obvious. Worst of all, there are signs that he's using Skagboys as a teaching aid. Brief socio-historical pass notes are included every couple of chapters for the benefit of anyone too young, too posh or too English to have noticed what was happening to Scotland during the 1980s. Optimum laboratory conditions, in other words, for a disastrous read.

Except that Skagboys isn't. We start out back in the days when Mark Renton is clean and reading for joint honours at Aberdeen Uni. He and Sick Boy take their first fix. Renton's brother Wee Davie dies. The heroin begins to take hold. His family begin to disintegrate and the good girls fall away. He drops out of university and goes to work on the boats. "Schopenhauer was right," Renton thinks: "life has tae be aboot disillusionment; stumbling inexorably towards the totally fucked."

For anyone who loved Trainspotting first time around there's something deeply cheering about returning to Welsh's world. "Are you sexually active?'' asks the woman at the Aids clinic. "Usually, aye, Keezbo goes, no gittin her at aw – but sometimes ah jist like tae lie back wi a bird oan top…"

For those who want to be shocked, there's plenty of provocation – Renton tossing off his "spasticated" brother, puppies down rubbish chutes munching on aborted foetuses, a memorable incident involving budgies and a mastectomy – and plenty of perfect moments: Renton torn by "resentment and tenderness" beside his grieving parents, Begbie raging at others for admiring his singing voice, Renton and Sick Boy wound round each other like bindweed.

And many of Welsh's wider points are well made. His "Notes on an Epidemic" include a couple of monthly lists of reported HIV-positive cases: 39 names, each with their terrible case histories summed up in a sentence. "If being Scottish is about one thing, it's aboot gittin fucked up," Renton explains. "Tae us intoxication isnae just a huge laugh or even a basic human right. It's a way ay life, a political philosophy."

And then things go slack and you can sense Welsh's concentration wandering. Twenty years later, he's too far from a world he was already distanced from when Trainspotting came out. Besides, part of the problem of writing about drugs is that almost by definition, every fix gets a little less interesting: heroin, like happiness, starts to write white. For hardcore enthusiasts, Skagboys' more measured pace and broad overview is a treat. For everyone else Trainspotting said it all, and said it better.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh

Re: Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh

Irvine Welsh: 'I'm the same kind of writer as I am a drinker. I'm a binger'

The Trainspotting author has returned to Renton, Sick Boy and Begbie with Skagboys, a prequel to his best-selling debut novel. He explains why he continues to explore those 'dark places'

Decca Aitkenhead

guardian.co.uk, Sunday 15 April 2012 20.00 BST

Irvine Welsh photographed in Leith, Edinburgh. Photograph: Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

When Irvine Welsh began writing 20 years ago, he hadn't much of a clue how to set about a novel. To get himself going, he hammered out 100,000 words, telling himself it was "just my launch pad to get into what I need to write about" – and sure enough the trick worked. The first 100,000 words were duly discarded, and lay forgotten for years, while the debut novel – Trainspotting – turned its author into a literary superstar.

Skagboys

by Irvine Welsh

Six more novels later, Welsh had an idea to dig those old words out again. They were stored on floppy disks he couldn't even read, so he found a data recovery expert on the internet, posted the disks off, and wondered what, if anything, would come back. "I was terrified that it would just get lost in the post. But if it was meant to be it was meant to be. I just thought: 'Oh well, I can't even remember what was on them anyway.'"

When the words returned safely, Welsh figured the next step would be straightforward. "Naively, I thought, well, I've got 100,000 words here, this should be all right," and so he sat down to write a prequel to Trainspotting. But immersing himself once again into the violent, darkly comic, chillingly affectless, uproariously chaotic world of his famous fictional junkies, Welsh ended up writing an epic so weighty and sprawling, it leaves Trainspotting looking like a footnote. "I just got into it," Welsh grins cheerfully. "It was fun. It was like meeting a bunch of old pals."

The book revisits Trainspotting's cast of Renton, Sick Boy, Begbie and co, following the group's early flirtations with heroin before they slowly descend into full-blown addiction. I found it an enjoyable but increasingly frustrating read, because for all the brilliance of Welsh's dialogue, and the compelling dramas of his characters, the lack of any discernible narrative momentum defeated me before I could get to the end. To his critics, Skagboys will probably confirm that Welsh only ever really had one good idea for a novel, and has been trading off it with diminishing returns ever since, indulged by editors too in awe of his fame to impose editorial discipline. To fans of Welsh's disregard for literary convention, on the other hand, a bumper second helping of their favourite characters will probably only make them love him even more.

This impression of a semi-delinquent literary gatecrasher played a big part in Welsh's early popular appeal, and I think he must be fond of the identity too, because it's still how he presents himself today. We meet in an Edinburgh bar, and he's not just smiley and relaxed but astonishingly inarticulate, getting tangled up in sentences that stop and start and wander off at will, until a great gust of his laughter swallows them up.

"I was in this shop in Edinburgh one time," he chuckles, "and this wee guy comes up to me like: 'You're Irvine Welsh, aren't you?' And I goes: 'Aye, I am.' And he said: 'I've read every one of your books.' And I said: 'Oh that's great.' And he goes: 'I fucking stole them all, I never paid for one.' Well that's brilliant!" People who secretly take themselves very seriously sometimes pretend not to by confecting an elaborate pretence of irreverence. But in Welsh's case, I would guess that the mischievous amusement is entirely authentic.

I tell him I'm not sure if he's a poster boy for recreational drug use – "Or the warning sign," he interjects, laughing. "I'm not sure myself sometimes." Trainspotting's influence on drug education campaigns does, he admits, entertain him. "If you look at all the drug education stuff, the anti-drug propaganda, it's practically been lifted right out of Trainspotting. And did I get a CBE or a knighthood or anything like that? No!" But he's not very comfortable about adopting any public position on drugs. "Obviously you want people to look after themselves and be safe, but it's basically up to them, you know. I don't really give a fuck what people do in terms of drugs."

Whether he likes it or not, though, Skagboys draws Welsh into this moral territory. A prequel to Trainspotting must explain why young men in the tenements of Leith swapped traditional Scottish working-class family life for the squalid despair of heroin addiction, and the novel implicates everything from Thatcherism to family bereavement. But Welsh tried very hard, he says, not to write a crude socio-economic polemic.

"Not, 'Oh, they shut down this factory and now we've got nothing to do, let's take drugs,' kind of thing. But just to show, without making a big point about it, that the dynamics within the relationships and the family relationships started to change. The idea of people who were basically stuck in a house with nothing to do all day long, it's like the Christmas syndrome, when you all get together at Christmas and think this is going to be great, but it's a fucking nightmare. Everyone needs some kind of compelling drama in their life, basically. You could look at it from the other way around, and you say why wouldn't people take drugs, because there's nothing else."

In that respect, Trainspotting's prequel is uncannily timely, for the very unemployment and social deprivation it catalogues is happening again today. "Well I didn't quite see that coming," Welsh laughs. "It wasn't like, as soon as the Conservatives got back into power, oh I must get this book out!"

Welsh himself is an interesting case study because despite growing up in the poverty of Leith, he didn't suffer any serious damage in his childhood. "I wasn't gang-banged by five uncles, you know?" Leaving school at 16, he muddled through a series of manual jobs before heading off to London in the 70s, where he wound up working for Hackney council and getting married. And yet along the way he nevertheless managed to get heavily addicted to heroin.

Why did he ever try it? "Stupidity, really," he admits. "And ignorance." Having been told by everyone that one spliff would kill him, the discovery that this was not in fact true discredited every other drug warning he'd ever heard. "So after that it was like, oh, a line of speed? Yeah. Smack? Yeah."

But unlike many of his contemporaries, he had enough of a life beyond addiction to be worth fighting for. He went cold turkey, kicked the habit, and the couple returned to Edinburgh, where Welsh worked for the council and studied for an MBA. Post-heroin, he was quite scared of drugs – until the early 90s rave scene and ecstasy seduced him, and inspired him to write.

Welsh's famously enthusiastic recreational drug consumption has slowly diminished in recent years, but only because it's no longer worth it. "I used to be able to go out, get fucked up, get up the next day and be fine. Now I just want to go back to bed and feel sorry for myself and kind of lie around sweating and groaning and all that." The trouble is, fans keep trying to give him drugs.

"I'll be doing a reading or a signing and people will come up to me and …" He mimes slipping drugs into his hand. "It's like: 'Oh fuck, there's a couple of grams of charlie and loads of fucking dope.'" Some of them even hand him heroin. "They want to be able to say they've given you something. But it's like, it's a waste, because it goes down the fucking pan all the time. And I really have to watch it," he adds, starting to chuckle, "because if I'm doing a book tour in America, for example, because it's a long distance, you're on planes all the time. There's been times where I've just forgotten and I've been sitting on the plane, put my hand in my pocket and found a little packet. I really do have to watch that."

Irvine Welsh and his wife Beth Quinn in 2009. Photograph: Barbara Lindberg/Rex Features

Welsh's life today is unrecognisable from the one he evokes in Skagboys and Trainspotting. He divides his time between Chicago, Miami and LA, and recently married for a second time, to a woman 22 years younger than him who rides dressage horses. The couple recently bought a horse, and Welsh admits: "I'm totally embarrassed, but I love this fucking horse. I don't ride him and ask him to do any work, I just talk to him and feed him nice treats so he loves me and he always tries to kiss me when I come into the stable. We've become new pals, I go out all the time to see him."

At 53 he remains childless – to his immense relief, for having felt too young to be a parent in his 20s and 30s, he says he missed the "10-minute window" and now feels too old. "I'm probably a natural uncle. I can take the kids out and have fun with them and look after them, and I can be Mr Popular. But actually having to do the grind? That stuff just doesn't appeal at all." If the 31-year-old Mrs Welsh decides she wants children, he will go along with it. "Well, you have to roll with it. But I still dread it. I live in fear."

Children would help solve the problem of isolation, though, which comes with being a writer. Welsh's solution used to be to DJ in nightclubs. "Otherwise you're sitting there alone with people that don't exist, and it's not good for me. I go fucking nuts. I just become weird and antisocial." These days, on account of the hangover problem, his remedy is film. "I go to Hollywood, and meet people, and it's fun. I've been doing a bit of screenwriting, and producing, and even a bit of directing." A movie of another Welsh novel, Filth, will be released later this year, starring James McAvoy, and the author thinks it's going to be bigger than Trainspotting. "I just can't see anything as good coming out of Britain in a long, long time. This is just so different from anything else. Completely original."

Welsh doesn't seem to suffer much angst or self-doubt, which is part of his enormous charm, and perhaps not surprising, because as he says himself: "Writing has been handed to me on a plate." He never even had to find an agent; the first big London publisher he submitted Trainspotting to snapped it up, and his publishers have been happy to print pretty much whatever he writes ever since. "I come up with a blurb at the beginning, but the book'll always be completely different by the time it's finished. They say: 'Where's the book you were going to write?' And I say, forget about it, it doesn't exist."

On the face of it, this should be every writer's dream, but in truth none of Welsh's novels have come close to the impact of his first, and I wonder if such sensational early success was in fact a mixed blessing. "Oh aye," he jokes, "it's all downhill from there." More seriously, he goes on: "You have to see it as a calling card, rather than an albatross around your neck, and you have to go into it with that attitude. I think I've written a lot better books than Trainspotting. Mind you," he adds, grinning, "I've written some really shit ones as well." Which ones are which? "I'm not going to tell you! I've still got to try and sell these things, for God's sake!"

Any attempt to impose discipline on his creativity would, by the sounds of it, probably be futile anyway. "It's just a big mess," is how he describes his approach to plot. "And I think, all this shit here has got to be put into some kind of order. It's like a police kind of thing, I've got the whiteboards on the walls and I've got all the pictures I've taken of different things, and stuff that I've taken off the net, and Post-it notes that I've scribbled on all over the wall. And there I am mixing it all around, taking it off the wall, putting it back up again." The writing process itself is equally chaotic.

"I'm the same kind of writer as I am a drinker. I'm a binger. Abstinence followed by ... well it's an addict thing, I'll sit there and my eyes will hanging out my head, it'll be five days later, unshaven not changed, really, really bad. And eventually I'll just get told: 'You fucking minging bastard, get a shower, for fuck's sake.' And then I'll get in the shower and be like, this is good, I'm going for a walk. I'm off down the pub."

For such an untortured soul, the puzzle for many readers is why he always writes about transgression and darkness. Some grotesque sort of sexual or violent abomination is pretty much ubiquitous in his novels, and critics have accused him of being a literary shock jock, but Welsh says mildly: "Well everybody that writes has their own area of inquiry. And mine has always been kind of, why is it that when life can be so hard and difficult, we compound it by self-sabotage, doing terrible things. That's always been my main area of inquiry, and it does lead you to dark places."

But success has, of course, led him away from the poverty of his youth, into a sunny life of dressage horses and Hollywood parties. A suspicion of inauthenticity – or worse still, of misery tourism – has attached itself to Welsh ever since he wrote Trainspotting, and I wonder if he's experienced a form of survivor's guilt for escaping the tragedy of his old friends' lives in Leith, chiefly by writing about them.

"No it brings massive fucking relief, to be perfectly honest. You can get into that drug-taking competition, and there's always somebody who's done more drugs than you, is more fucked-up than you. But they've got to actually write a book about it. Nobody's going to sign a royalty cheque because they've done more drugs than me, you know what I mean?"

When his debut first came out and sold 10,000 copies, "I was like the hero. 'You're fuckin' tellin' our story, good on yer, telling it as it is. Go on son.' But when it sold 100,000 copies they said: 'What the fuck?' About the same book! I mean, every psychopath in Leith thinks they're Begbie. And whenever there's a book out, everyone looks at me kind of funny when I come back, almost like to see if I've changed." They're checking to see if he's turned into a tosser? "It's a bit late for that," he laughs. "Cos I started off at that point."

The Trainspotting author has returned to Renton, Sick Boy and Begbie with Skagboys, a prequel to his best-selling debut novel. He explains why he continues to explore those 'dark places'

Decca Aitkenhead

guardian.co.uk, Sunday 15 April 2012 20.00 BST

Irvine Welsh photographed in Leith, Edinburgh. Photograph: Murdo MacLeod for the Guardian

When Irvine Welsh began writing 20 years ago, he hadn't much of a clue how to set about a novel. To get himself going, he hammered out 100,000 words, telling himself it was "just my launch pad to get into what I need to write about" – and sure enough the trick worked. The first 100,000 words were duly discarded, and lay forgotten for years, while the debut novel – Trainspotting – turned its author into a literary superstar.

Skagboys

by Irvine Welsh

Six more novels later, Welsh had an idea to dig those old words out again. They were stored on floppy disks he couldn't even read, so he found a data recovery expert on the internet, posted the disks off, and wondered what, if anything, would come back. "I was terrified that it would just get lost in the post. But if it was meant to be it was meant to be. I just thought: 'Oh well, I can't even remember what was on them anyway.'"

When the words returned safely, Welsh figured the next step would be straightforward. "Naively, I thought, well, I've got 100,000 words here, this should be all right," and so he sat down to write a prequel to Trainspotting. But immersing himself once again into the violent, darkly comic, chillingly affectless, uproariously chaotic world of his famous fictional junkies, Welsh ended up writing an epic so weighty and sprawling, it leaves Trainspotting looking like a footnote. "I just got into it," Welsh grins cheerfully. "It was fun. It was like meeting a bunch of old pals."

The book revisits Trainspotting's cast of Renton, Sick Boy, Begbie and co, following the group's early flirtations with heroin before they slowly descend into full-blown addiction. I found it an enjoyable but increasingly frustrating read, because for all the brilliance of Welsh's dialogue, and the compelling dramas of his characters, the lack of any discernible narrative momentum defeated me before I could get to the end. To his critics, Skagboys will probably confirm that Welsh only ever really had one good idea for a novel, and has been trading off it with diminishing returns ever since, indulged by editors too in awe of his fame to impose editorial discipline. To fans of Welsh's disregard for literary convention, on the other hand, a bumper second helping of their favourite characters will probably only make them love him even more.

This impression of a semi-delinquent literary gatecrasher played a big part in Welsh's early popular appeal, and I think he must be fond of the identity too, because it's still how he presents himself today. We meet in an Edinburgh bar, and he's not just smiley and relaxed but astonishingly inarticulate, getting tangled up in sentences that stop and start and wander off at will, until a great gust of his laughter swallows them up.

"I was in this shop in Edinburgh one time," he chuckles, "and this wee guy comes up to me like: 'You're Irvine Welsh, aren't you?' And I goes: 'Aye, I am.' And he said: 'I've read every one of your books.' And I said: 'Oh that's great.' And he goes: 'I fucking stole them all, I never paid for one.' Well that's brilliant!" People who secretly take themselves very seriously sometimes pretend not to by confecting an elaborate pretence of irreverence. But in Welsh's case, I would guess that the mischievous amusement is entirely authentic.

I tell him I'm not sure if he's a poster boy for recreational drug use – "Or the warning sign," he interjects, laughing. "I'm not sure myself sometimes." Trainspotting's influence on drug education campaigns does, he admits, entertain him. "If you look at all the drug education stuff, the anti-drug propaganda, it's practically been lifted right out of Trainspotting. And did I get a CBE or a knighthood or anything like that? No!" But he's not very comfortable about adopting any public position on drugs. "Obviously you want people to look after themselves and be safe, but it's basically up to them, you know. I don't really give a fuck what people do in terms of drugs."

Whether he likes it or not, though, Skagboys draws Welsh into this moral territory. A prequel to Trainspotting must explain why young men in the tenements of Leith swapped traditional Scottish working-class family life for the squalid despair of heroin addiction, and the novel implicates everything from Thatcherism to family bereavement. But Welsh tried very hard, he says, not to write a crude socio-economic polemic.

"Not, 'Oh, they shut down this factory and now we've got nothing to do, let's take drugs,' kind of thing. But just to show, without making a big point about it, that the dynamics within the relationships and the family relationships started to change. The idea of people who were basically stuck in a house with nothing to do all day long, it's like the Christmas syndrome, when you all get together at Christmas and think this is going to be great, but it's a fucking nightmare. Everyone needs some kind of compelling drama in their life, basically. You could look at it from the other way around, and you say why wouldn't people take drugs, because there's nothing else."

In that respect, Trainspotting's prequel is uncannily timely, for the very unemployment and social deprivation it catalogues is happening again today. "Well I didn't quite see that coming," Welsh laughs. "It wasn't like, as soon as the Conservatives got back into power, oh I must get this book out!"

Welsh himself is an interesting case study because despite growing up in the poverty of Leith, he didn't suffer any serious damage in his childhood. "I wasn't gang-banged by five uncles, you know?" Leaving school at 16, he muddled through a series of manual jobs before heading off to London in the 70s, where he wound up working for Hackney council and getting married. And yet along the way he nevertheless managed to get heavily addicted to heroin.

Why did he ever try it? "Stupidity, really," he admits. "And ignorance." Having been told by everyone that one spliff would kill him, the discovery that this was not in fact true discredited every other drug warning he'd ever heard. "So after that it was like, oh, a line of speed? Yeah. Smack? Yeah."

But unlike many of his contemporaries, he had enough of a life beyond addiction to be worth fighting for. He went cold turkey, kicked the habit, and the couple returned to Edinburgh, where Welsh worked for the council and studied for an MBA. Post-heroin, he was quite scared of drugs – until the early 90s rave scene and ecstasy seduced him, and inspired him to write.

Welsh's famously enthusiastic recreational drug consumption has slowly diminished in recent years, but only because it's no longer worth it. "I used to be able to go out, get fucked up, get up the next day and be fine. Now I just want to go back to bed and feel sorry for myself and kind of lie around sweating and groaning and all that." The trouble is, fans keep trying to give him drugs.

"I'll be doing a reading or a signing and people will come up to me and …" He mimes slipping drugs into his hand. "It's like: 'Oh fuck, there's a couple of grams of charlie and loads of fucking dope.'" Some of them even hand him heroin. "They want to be able to say they've given you something. But it's like, it's a waste, because it goes down the fucking pan all the time. And I really have to watch it," he adds, starting to chuckle, "because if I'm doing a book tour in America, for example, because it's a long distance, you're on planes all the time. There's been times where I've just forgotten and I've been sitting on the plane, put my hand in my pocket and found a little packet. I really do have to watch that."

Irvine Welsh and his wife Beth Quinn in 2009. Photograph: Barbara Lindberg/Rex Features

Welsh's life today is unrecognisable from the one he evokes in Skagboys and Trainspotting. He divides his time between Chicago, Miami and LA, and recently married for a second time, to a woman 22 years younger than him who rides dressage horses. The couple recently bought a horse, and Welsh admits: "I'm totally embarrassed, but I love this fucking horse. I don't ride him and ask him to do any work, I just talk to him and feed him nice treats so he loves me and he always tries to kiss me when I come into the stable. We've become new pals, I go out all the time to see him."

At 53 he remains childless – to his immense relief, for having felt too young to be a parent in his 20s and 30s, he says he missed the "10-minute window" and now feels too old. "I'm probably a natural uncle. I can take the kids out and have fun with them and look after them, and I can be Mr Popular. But actually having to do the grind? That stuff just doesn't appeal at all." If the 31-year-old Mrs Welsh decides she wants children, he will go along with it. "Well, you have to roll with it. But I still dread it. I live in fear."

Children would help solve the problem of isolation, though, which comes with being a writer. Welsh's solution used to be to DJ in nightclubs. "Otherwise you're sitting there alone with people that don't exist, and it's not good for me. I go fucking nuts. I just become weird and antisocial." These days, on account of the hangover problem, his remedy is film. "I go to Hollywood, and meet people, and it's fun. I've been doing a bit of screenwriting, and producing, and even a bit of directing." A movie of another Welsh novel, Filth, will be released later this year, starring James McAvoy, and the author thinks it's going to be bigger than Trainspotting. "I just can't see anything as good coming out of Britain in a long, long time. This is just so different from anything else. Completely original."

Welsh doesn't seem to suffer much angst or self-doubt, which is part of his enormous charm, and perhaps not surprising, because as he says himself: "Writing has been handed to me on a plate." He never even had to find an agent; the first big London publisher he submitted Trainspotting to snapped it up, and his publishers have been happy to print pretty much whatever he writes ever since. "I come up with a blurb at the beginning, but the book'll always be completely different by the time it's finished. They say: 'Where's the book you were going to write?' And I say, forget about it, it doesn't exist."

On the face of it, this should be every writer's dream, but in truth none of Welsh's novels have come close to the impact of his first, and I wonder if such sensational early success was in fact a mixed blessing. "Oh aye," he jokes, "it's all downhill from there." More seriously, he goes on: "You have to see it as a calling card, rather than an albatross around your neck, and you have to go into it with that attitude. I think I've written a lot better books than Trainspotting. Mind you," he adds, grinning, "I've written some really shit ones as well." Which ones are which? "I'm not going to tell you! I've still got to try and sell these things, for God's sake!"

Any attempt to impose discipline on his creativity would, by the sounds of it, probably be futile anyway. "It's just a big mess," is how he describes his approach to plot. "And I think, all this shit here has got to be put into some kind of order. It's like a police kind of thing, I've got the whiteboards on the walls and I've got all the pictures I've taken of different things, and stuff that I've taken off the net, and Post-it notes that I've scribbled on all over the wall. And there I am mixing it all around, taking it off the wall, putting it back up again." The writing process itself is equally chaotic.

"I'm the same kind of writer as I am a drinker. I'm a binger. Abstinence followed by ... well it's an addict thing, I'll sit there and my eyes will hanging out my head, it'll be five days later, unshaven not changed, really, really bad. And eventually I'll just get told: 'You fucking minging bastard, get a shower, for fuck's sake.' And then I'll get in the shower and be like, this is good, I'm going for a walk. I'm off down the pub."

For such an untortured soul, the puzzle for many readers is why he always writes about transgression and darkness. Some grotesque sort of sexual or violent abomination is pretty much ubiquitous in his novels, and critics have accused him of being a literary shock jock, but Welsh says mildly: "Well everybody that writes has their own area of inquiry. And mine has always been kind of, why is it that when life can be so hard and difficult, we compound it by self-sabotage, doing terrible things. That's always been my main area of inquiry, and it does lead you to dark places."

But success has, of course, led him away from the poverty of his youth, into a sunny life of dressage horses and Hollywood parties. A suspicion of inauthenticity – or worse still, of misery tourism – has attached itself to Welsh ever since he wrote Trainspotting, and I wonder if he's experienced a form of survivor's guilt for escaping the tragedy of his old friends' lives in Leith, chiefly by writing about them.

"No it brings massive fucking relief, to be perfectly honest. You can get into that drug-taking competition, and there's always somebody who's done more drugs than you, is more fucked-up than you. But they've got to actually write a book about it. Nobody's going to sign a royalty cheque because they've done more drugs than me, you know what I mean?"

When his debut first came out and sold 10,000 copies, "I was like the hero. 'You're fuckin' tellin' our story, good on yer, telling it as it is. Go on son.' But when it sold 100,000 copies they said: 'What the fuck?' About the same book! I mean, every psychopath in Leith thinks they're Begbie. And whenever there's a book out, everyone looks at me kind of funny when I come back, almost like to see if I've changed." They're checking to see if he's turned into a tosser? "It's a bit late for that," he laughs. "Cos I started off at that point."

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Similar topics

Similar topics» Curious silence of To Kill a Mockingbird author Harper Lee

» Iain Sinclair: London 2012 Olympics development project provokes Welsh psychogeographer's rage

» Iain Sinclair: London 2012 Olympics development project provokes Welsh psychogeographer's rage

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum