The Horse in Art

+3

senorita

john smith0341

eddie

7 posters

Page 1 of 2

Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

The Horse in Art

The Horse in Art

British Museum canters through 5,000 years of equine history

A celebration of the horse – from newly excavated Saudi Arabian rock carvings to Victorian London's dung dilemma

Maev Kennedy

guardian.co.uk, Monday 2 January 2012 18.33 GMT

A fragment of an Assyrian 9th-century BC carved limestone relief from Nimrud, Iraq.

The British Museum is planning its first exhibition devoted to the horse, with a display tracing the animal's story across thousands of years of human history.

The exhibition will range from a stylised figure that decorated a 3,000-year-old harness, to the Georgian thoroughbreds Hambletonian and Diamond, immortalised on a gambler's gaming chip – appropriately since Hambletonian won a staggering 3,000 guinea prize when he beat Diamond by a short head at Newmarket in 1799.

Curator John Curtis said: "There are probably horses somewhere in every gallery in the museum, from Assyrian sculptures to coins. They're so familiar and ubiquitous they mostly go unnoticed. We want to bring them together and show their importance in history. The horse was an engine of human development and, until a generation ago, part of the everyday experience of life even in the heart of London."

There were so many horses in Victorian London that one solemn calculation concluded that the city would become uninhabitable by the turn of the 20th century, buried under a rising tide of dung. "And now they're gone completely in one lifetime," co-curator Nigel Tallis said sadly. "Many city dwellers will never see a horse in the street except police horses and the odd procession, and yet from mews to horse troughs, the city is still full of evidence of their day." The exhibition will bring together scores of horses from the museum's own collection, including a miniature gold chariot drawn by four horses, made around 2,500 years ago, part of the Oxus treasure hoard of ancient Persian gold.

The loans will include paintings by George Stubbs, newly excavated carvings of horses from Saudi Arabia, panoramic photographs of incised horses on rock faces which may be thousands of years old, clay tablets promising gifts of horses and chariots, and beautiful harness decorations, some in pure gold.

Until the development of artillery, a skilled archer on horseback was the most dangerous weapon in any war. The exhibition will include two complete sets of Islamic and western horse armour from the royal armouries.

The wild horse was domesticated at least 5,000 years ago and probably far earlier, initially for meat and later for transport, transforming how far a man could travel and how much he could carry. The exhibition traces the evolution of the elegant, swift Arabian horses, associated in legend with King Solomon and Muhammad. Said to have been created by angels or born out of the wind, they were prized more highly than gold, and made suitable gifts for princes and emperors.

Their distinctive, high-arched necks and tails can be seen in Assyrian sculptures, Egyptian wall paintings and ancient Greek vases, and the exhibition will also trace the bloodlines of all modern thoroughbreds back to three famous Arabian stallions imported into 18th-century England: the Darley Arabian, the Byerly Turk and the Godolphin Arabian.

Curtis, whose career as an archaeologist has been devoted to the ancient near east, can testify to their speed: when he turned back from a site visit in Iran and his horse sensed he was homeward bound, it bolted, leaving him clinging to its mane. Loans from the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge will trace the history of the Crabbet Arabian Stud, complete with a bedouin tent for entertaining visitors, at Crabbet Park in West Sussex, where the writer and diplomat Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and his wife, Anne – granddaughter of the poet Byron – imported and bred Arabian horses, eventually dividing the collection when his string of mistresses led to their separation.

The free exhibition, which will open in May, has been timed to coincide with the Olympic Games, but has also been conceived as a diamond jubilee gift to another celebrated horse breeder, the Queen.

The Horse: Ancient Arabia to the Modern World, 24 May – 30 September

A celebration of the horse – from newly excavated Saudi Arabian rock carvings to Victorian London's dung dilemma

Maev Kennedy

guardian.co.uk, Monday 2 January 2012 18.33 GMT

A fragment of an Assyrian 9th-century BC carved limestone relief from Nimrud, Iraq.

The British Museum is planning its first exhibition devoted to the horse, with a display tracing the animal's story across thousands of years of human history.

The exhibition will range from a stylised figure that decorated a 3,000-year-old harness, to the Georgian thoroughbreds Hambletonian and Diamond, immortalised on a gambler's gaming chip – appropriately since Hambletonian won a staggering 3,000 guinea prize when he beat Diamond by a short head at Newmarket in 1799.

Curator John Curtis said: "There are probably horses somewhere in every gallery in the museum, from Assyrian sculptures to coins. They're so familiar and ubiquitous they mostly go unnoticed. We want to bring them together and show their importance in history. The horse was an engine of human development and, until a generation ago, part of the everyday experience of life even in the heart of London."

There were so many horses in Victorian London that one solemn calculation concluded that the city would become uninhabitable by the turn of the 20th century, buried under a rising tide of dung. "And now they're gone completely in one lifetime," co-curator Nigel Tallis said sadly. "Many city dwellers will never see a horse in the street except police horses and the odd procession, and yet from mews to horse troughs, the city is still full of evidence of their day." The exhibition will bring together scores of horses from the museum's own collection, including a miniature gold chariot drawn by four horses, made around 2,500 years ago, part of the Oxus treasure hoard of ancient Persian gold.

The loans will include paintings by George Stubbs, newly excavated carvings of horses from Saudi Arabia, panoramic photographs of incised horses on rock faces which may be thousands of years old, clay tablets promising gifts of horses and chariots, and beautiful harness decorations, some in pure gold.

Until the development of artillery, a skilled archer on horseback was the most dangerous weapon in any war. The exhibition will include two complete sets of Islamic and western horse armour from the royal armouries.

The wild horse was domesticated at least 5,000 years ago and probably far earlier, initially for meat and later for transport, transforming how far a man could travel and how much he could carry. The exhibition traces the evolution of the elegant, swift Arabian horses, associated in legend with King Solomon and Muhammad. Said to have been created by angels or born out of the wind, they were prized more highly than gold, and made suitable gifts for princes and emperors.

Their distinctive, high-arched necks and tails can be seen in Assyrian sculptures, Egyptian wall paintings and ancient Greek vases, and the exhibition will also trace the bloodlines of all modern thoroughbreds back to three famous Arabian stallions imported into 18th-century England: the Darley Arabian, the Byerly Turk and the Godolphin Arabian.

Curtis, whose career as an archaeologist has been devoted to the ancient near east, can testify to their speed: when he turned back from a site visit in Iran and his horse sensed he was homeward bound, it bolted, leaving him clinging to its mane. Loans from the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge will trace the history of the Crabbet Arabian Stud, complete with a bedouin tent for entertaining visitors, at Crabbet Park in West Sussex, where the writer and diplomat Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and his wife, Anne – granddaughter of the poet Byron – imported and bred Arabian horses, eventually dividing the collection when his string of mistresses led to their separation.

The free exhibition, which will open in May, has been timed to coincide with the Olympic Games, but has also been conceived as a diamond jubilee gift to another celebrated horse breeder, the Queen.

The Horse: Ancient Arabia to the Modern World, 24 May – 30 September

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Whistlejacket is an oil-on-canvas painting from about 1762 by British artist George Stubbs showing the Marquess of Rockingham's racehorse, rearing up against a blank background. The huge canvas, lack of other features, and Stubbs' attention to the minute details of the horse's appearance give the portrait a powerful physical presence. It has been described in The Independent as "a paradigm of the flawless beauty of an Arabian thoroughbred".

Stubbs' knowledge of equine physiology was unsurpassed by any painter; he had studied anatomy at York and, from 1756, he spent 18 months in Lincolnshire where he carried out dissections and experiments on dead horses to better understand the animal's physiology, suspending the cadavers with block and tackle to sketch them in different positions. The careful notes and drawings he made during his studies were published in 1766 as The Anatomy of the Horse.

(Wikipedia)

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

A Lion Attacking a Horse, oil on canvas, 1770, by Stubbs. Yale University Art Gallery.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Finished Study for the Fifth Anatomical Table. c. 1756-7. Graphite on paper. Royal collection, UK.

Last edited by eddie on Wed Jan 04, 2012 12:34 am; edited 1 time in total

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Cover of Camarón album Potro de rabia y miel (Fury and honey colt) by Miquel Barceló

and this is what it sounds like:

Guest- Guest

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Man and Horse- Dr Gunter Von Hagen's Bodyworlds exhibition

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

The Grand Procession of the Wellington Statue, Turning Down Park Lane' The Illustrated London News 3 October 1846

The restored statue today. Wellington astride Copenhagen, the horse he rode all day at the battle of Waterloo.

Copenhagen and the Duke became synonymous and even in retirement from war they remained together. The Iron Duke, as he was affectionately known, became Prime Minister of Britain in 1828 and rode Copenhagen up Downing Street to No.10 to take up his new position of leadership.

In retirement the old horse must have become somewhat mellowed because he was regularly ridden by friends and children at the Duke's country estate of Stratfield Saye, although Lady Shelley said he was the most difficult to sit of any horse she had ever ridden. The Duchess often fed him with bread and this it was said gave him the habit of approaching every lady with the most confiding familiarity. Over the years hair had been taken from the horse and made into bracelets for the ladies.

When the great horse died in 1836, at the remarkable age of 29, he was given a funeral with full military honors. But the day was worsened for the Duke who noticed that one hoof had been removed and flew into a terrible passion about the mutilation. After his own death the guilty servant who had taken the hoof as a memento came forward to confess and presented it to the second Duke who had it made into an inkstand.

The War Museum approached the Duke about disinterring Copenhagen in order to keep his skeleton in the Museum alongside the skeleton of Napoleon's horse, Marengo. But the Duke thwarted the idea by saying he was not sure exactly where the horse had been buried. Of course, he knew precisely where Copenhagen's remains were under the turkey oak in the Ice House Paddock at his country estate at Stratfield Saye but obviously preferred to keep his loyal friend at home with him.

As a mark of respect the second Duke erected a stone marker on the grave where it remains to this day.

Last edited by eddie on Wed Jan 04, 2012 12:56 am; edited 1 time in total

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Napoleon Crossing the Alps painted by Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), oil on canvas, 259 cm x 221 cm (8' 6" x 7' 3"), 1800. Horse in the painting is believed to be Marengo.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Alexander the Great taming his horse Bucephalus.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Detail of Don Quijote's tired and skinny horse, Rocinante (by L. Coullaut, Madrid)

Guest- Guest

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

The Horse: From Arabia to Royal Ascot – review

British Museum, London

Kate Kellaway

The Observer, Sunday 27 May 2012

Rearing to go: Laetitia, Lady Lade, 1793 by George Stubbs: ‘a fantastic glorification of horsewomanship’. Photograph: The Royal Collection

The British Museum is a most distinguished and well-stocked stable. You walk into its Great Court and at once spot the emperor Hadrian, mounted on his stone steed, legs dangling, just beyond the information desk. And this is before you've even set foot in the museum's tremendous exhibition – its first devoted to the horse. It's the perfect moment for a celebration. The idea of the horse show was raised in the 90s but has had to wait for the Olympics to give it an extra leg-up. War Horse, in all its manifestations, has contributed extra enthusiasm, and there is a third and royal reason for equine rejoicing: the exhibition is a diamond jubilee gift to the Queen.

John Curtis, one of the curators, explains that there has been much advance interest in the show. Horses, magnificently wordless in themselves, excite passionate differences of opinion in their admirers and the museum has been petitioned, urging that certain breeds be championed. But the museum has faced a challenge: "Most of our exhibitions are monocultural, whereas the horse exists in all cultures." And so partly to avoid a bewildering miscellany, the decision has been taken to put Arab horses in charge of the narrative.

The domestication of the horse is thought to have taken place on the western Euraisan steppes, probably in Kazakhstan, around 3,500BC (the exhibition includes what may be the earliest depiction of a horse and rider, a terracotta mound from Mesopotamia). But the narrative then advances through Islamic history and showcases the emergence of the Arab horse.

It reveals that the bloodlines of modern thoroughbreds can be traced back to three Arabian stallions imported into England in the 18th century (the Darley Arabian, the Byerley Turk and the Godolphin Arabian). The journey we take includes astounding Arab rock paintings of horses and then fetches up in Victorian England to consider the horse's influence on society (the horse traffic jams were terrible), before a racy finish at Ascot and in the modern world.

But we begin by putting the cart – or chariot – before the horse. The first room contains a most enigmatic treasure: the Standard of Ur, a tapered box (2600BC Sumerian) inlaid with a beautiful mosaic of shell, lapis lazuli and red limestone. No one knows what its purpose was but it seems extraordinary that its donkeys – yoked into service before the horse – with heads of fragile shell have survived and are still pulling unwieldy chariots that look disconcertingly like heavy brown prams.

The same room also contains a stunning black-and-white film of Arab horses placed alongside a fragment of an Assyrian 9th-century BC limestone relief. You look from three proud profiles in stone to the Arab horses on film and time becomes thrillingly fused, measured only by the unchanging outline of the horse.

The museum has been hard at work. There's an incredible reconstruction of an Assyrian chariot horse, its harness assembled in fragments – an academic ransacking of the British Museum's tack room. The stone blinkers appear alarmingly heavy. A second formidable warhorse wears late 15th-century Turkish armour and a third sports cheerful, quilted patchwork from 19th-century Sudan.

The exhibition reminds us that the horse is an object of decoration as well as a subject. A chic Egyptian wig-curler (c 1500-1000BC) features a rider and galloping horse – a touch of serpent in its bronze form. And most decorative of all are the exquisitely dainty and diminutive gold chariots (5th-4th century BC from Persia) with filigree reins – a fairy tale earthed in reality: the horses' tails tied in mud knots. And I also admired the 16th-century Turkish stirrups: black iron garlanded with golden flowers. They seem, centuries later, to be haunted by the riders who once put their feet in them.

There is a marvellous sense throughout of riding being celebrated. There's a captivating Indian watercolour (1650-1750), starring Akbar the Great out hunting, bent forward on his horse, with swirling deer around him, as if an eager gale were blowing through the picture. The poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, quoted in the exhibition's superb catalogue, seems to speak for Akbar and riders like him. In his poem St Valentine's Day he reveals that, for him, riding brought about glorious delusion: "My horse a thing of wings, myself a god."

It is Wilfrid Blunt and his wife, Lady Anne, who serve as a bridging device here, bringing the narrative to 19th-century England. They were a remarkable couple, staunch travellers with a passion for Arabia and a mission to preserve the integrity of the Arab horse. They imported horses to Crabbet Park, their West Sussex stud, and there is a priceless photograph of Lady Anne there, in full Arabian regalia, with her mare Kasida. You would laugh were it not for the fact that the woman and horse have a solemn affinity. The story of the Blunts is fascinating (although too complex to relate here). Suffice it to say, the love affair with the horse went better than the marriage.

Only one horsewoman trumps Lady Anne Blunt: Lady Lade. The exhibition would not be complete without George Stubbs, and there are two stupendous portraits here. Lady Lade, or Laetitia, was the mistress of a highwayman and went on to marry a racehorse owner – perhaps this is how she learned to ride. In Laetitia, Lady Lade (1793), she sits on a rearing horse, comically unmoved, the folds of her long blue dress undisturbed. She seems in another world, with an unruffled, crepuscular park behind her. It's a fantastic glorification of horsewomanship. In Gimcrack With John Pratt Up on Newmarket Heath (c1765), there is a similar stillness to the landscape. Another perfect day, but the jockey is inward, the horse's liquid eye shows apprehension – anything could happen.

Towards the end of the exhibition, Cymbeline's famous cry: "O, for a horse with wings!" is up on one of the walls. Yet the final room persuades us in photographs and films of some of the greatest competitive horses and riders alive, including the Queen's horse Free Agent who won at Ascot in 2008, that wings were never necessary.

British Museum, London

Kate Kellaway

The Observer, Sunday 27 May 2012

Rearing to go: Laetitia, Lady Lade, 1793 by George Stubbs: ‘a fantastic glorification of horsewomanship’. Photograph: The Royal Collection

The British Museum is a most distinguished and well-stocked stable. You walk into its Great Court and at once spot the emperor Hadrian, mounted on his stone steed, legs dangling, just beyond the information desk. And this is before you've even set foot in the museum's tremendous exhibition – its first devoted to the horse. It's the perfect moment for a celebration. The idea of the horse show was raised in the 90s but has had to wait for the Olympics to give it an extra leg-up. War Horse, in all its manifestations, has contributed extra enthusiasm, and there is a third and royal reason for equine rejoicing: the exhibition is a diamond jubilee gift to the Queen.

John Curtis, one of the curators, explains that there has been much advance interest in the show. Horses, magnificently wordless in themselves, excite passionate differences of opinion in their admirers and the museum has been petitioned, urging that certain breeds be championed. But the museum has faced a challenge: "Most of our exhibitions are monocultural, whereas the horse exists in all cultures." And so partly to avoid a bewildering miscellany, the decision has been taken to put Arab horses in charge of the narrative.

The domestication of the horse is thought to have taken place on the western Euraisan steppes, probably in Kazakhstan, around 3,500BC (the exhibition includes what may be the earliest depiction of a horse and rider, a terracotta mound from Mesopotamia). But the narrative then advances through Islamic history and showcases the emergence of the Arab horse.

It reveals that the bloodlines of modern thoroughbreds can be traced back to three Arabian stallions imported into England in the 18th century (the Darley Arabian, the Byerley Turk and the Godolphin Arabian). The journey we take includes astounding Arab rock paintings of horses and then fetches up in Victorian England to consider the horse's influence on society (the horse traffic jams were terrible), before a racy finish at Ascot and in the modern world.

But we begin by putting the cart – or chariot – before the horse. The first room contains a most enigmatic treasure: the Standard of Ur, a tapered box (2600BC Sumerian) inlaid with a beautiful mosaic of shell, lapis lazuli and red limestone. No one knows what its purpose was but it seems extraordinary that its donkeys – yoked into service before the horse – with heads of fragile shell have survived and are still pulling unwieldy chariots that look disconcertingly like heavy brown prams.

The same room also contains a stunning black-and-white film of Arab horses placed alongside a fragment of an Assyrian 9th-century BC limestone relief. You look from three proud profiles in stone to the Arab horses on film and time becomes thrillingly fused, measured only by the unchanging outline of the horse.

The museum has been hard at work. There's an incredible reconstruction of an Assyrian chariot horse, its harness assembled in fragments – an academic ransacking of the British Museum's tack room. The stone blinkers appear alarmingly heavy. A second formidable warhorse wears late 15th-century Turkish armour and a third sports cheerful, quilted patchwork from 19th-century Sudan.

The exhibition reminds us that the horse is an object of decoration as well as a subject. A chic Egyptian wig-curler (c 1500-1000BC) features a rider and galloping horse – a touch of serpent in its bronze form. And most decorative of all are the exquisitely dainty and diminutive gold chariots (5th-4th century BC from Persia) with filigree reins – a fairy tale earthed in reality: the horses' tails tied in mud knots. And I also admired the 16th-century Turkish stirrups: black iron garlanded with golden flowers. They seem, centuries later, to be haunted by the riders who once put their feet in them.

There is a marvellous sense throughout of riding being celebrated. There's a captivating Indian watercolour (1650-1750), starring Akbar the Great out hunting, bent forward on his horse, with swirling deer around him, as if an eager gale were blowing through the picture. The poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, quoted in the exhibition's superb catalogue, seems to speak for Akbar and riders like him. In his poem St Valentine's Day he reveals that, for him, riding brought about glorious delusion: "My horse a thing of wings, myself a god."

It is Wilfrid Blunt and his wife, Lady Anne, who serve as a bridging device here, bringing the narrative to 19th-century England. They were a remarkable couple, staunch travellers with a passion for Arabia and a mission to preserve the integrity of the Arab horse. They imported horses to Crabbet Park, their West Sussex stud, and there is a priceless photograph of Lady Anne there, in full Arabian regalia, with her mare Kasida. You would laugh were it not for the fact that the woman and horse have a solemn affinity. The story of the Blunts is fascinating (although too complex to relate here). Suffice it to say, the love affair with the horse went better than the marriage.

Only one horsewoman trumps Lady Anne Blunt: Lady Lade. The exhibition would not be complete without George Stubbs, and there are two stupendous portraits here. Lady Lade, or Laetitia, was the mistress of a highwayman and went on to marry a racehorse owner – perhaps this is how she learned to ride. In Laetitia, Lady Lade (1793), she sits on a rearing horse, comically unmoved, the folds of her long blue dress undisturbed. She seems in another world, with an unruffled, crepuscular park behind her. It's a fantastic glorification of horsewomanship. In Gimcrack With John Pratt Up on Newmarket Heath (c1765), there is a similar stillness to the landscape. Another perfect day, but the jockey is inward, the horse's liquid eye shows apprehension – anything could happen.

Towards the end of the exhibition, Cymbeline's famous cry: "O, for a horse with wings!" is up on one of the walls. Yet the final room persuades us in photographs and films of some of the greatest competitive horses and riders alive, including the Queen's horse Free Agent who won at Ascot in 2008, that wings were never necessary.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Well spotted: Cave paintings, such as the 25,000-year-old Dappled Horses of Pech-Merle, show horses with a spotted or 'leopard' coat. DNA evidence shows this is an accurate depiction of the animal's coat

Guest- Guest

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Stampede: Breathtaking art on the walls of the Hillaire Chamber of the Chauvet Cave in France. Black and bay horses are commonly depicted in cave art that dates back 25,000 years

Guest- Guest

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Panel Of The Chinese Horses: This painting, on the wall of the famous Lascaux Cave in south-western France, shows a more traditional colouring, which led to theories of the more elaborate paintings being symbolic

Guest- Guest

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

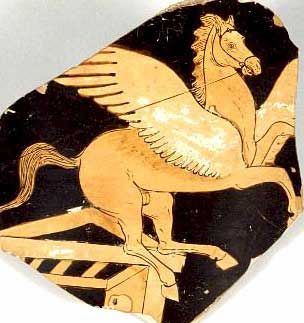

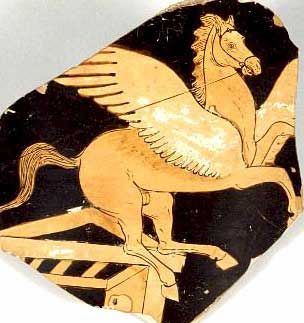

Pegasus for you:

Pauline Baynes' illustration.

Pauline Baynes' illustration.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

...now you're talking!

Pegasus at the spring, Apulian red-figure vase

C4th B.C., Tampa Museum of Art

Pegasus at the spring, Apulian red-figure vase

C4th B.C., Tampa Museum of Art

Guest- Guest

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Sun disk chariot, (Trundholm Horse Chariot) Denmark, 1800-1600 BCE*

Last edited by blue moon on Sun May 27, 2012 4:03 pm; edited 1 time in total

Guest- Guest

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

These all are very good but my question is when these will be made have you any idea?

john smith0341- Posts : 5

Join date : 2012-06-01

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

What's the frequency Kenneth?

Last edited by senorita panties on Sat Jan 05, 2013 10:19 am; edited 1 time in total

senorita- Posts : 362

Join date : 2012-07-11

Age : 27

Location : makgadikgadi pan

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

A GREEK BRONZE HORSE

GEOMETRIC PERIOD, CIRCA MID 8TH CENTURY B.C.

blue moon- Posts : 709

Join date : 2012-08-03

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

What's the frequency Kenneth?

Last edited by senorita panties on Sat Jan 05, 2013 10:19 am; edited 1 time in total

senorita- Posts : 362

Join date : 2012-07-11

Age : 27

Location : makgadikgadi pan

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

Charlie's a...unicorn.Blue Pinggo wrote:

blue moon- Posts : 709

Join date : 2012-08-03

Re: The Horse in Art

Re: The Horse in Art

What's the frequency Kenneth?

Last edited by senorita panties on Sat Jan 05, 2013 10:18 am; edited 1 time in total

senorita- Posts : 362

Join date : 2012-07-11

Age : 27

Location : makgadikgadi pan

Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Page 1 of 2

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum|

|

|