Charles Dickens

3 posters

Page 1 of 2

Page 1 of 2 • 1, 2

Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens bicentenary: Call for online editors to save forgotten journal

Three billion words in great author's weekly magazine are giving academics a massive proofreading problem

Tracy McVeigh guardian.co.uk, Saturday 6 August 2011 22.28 BST

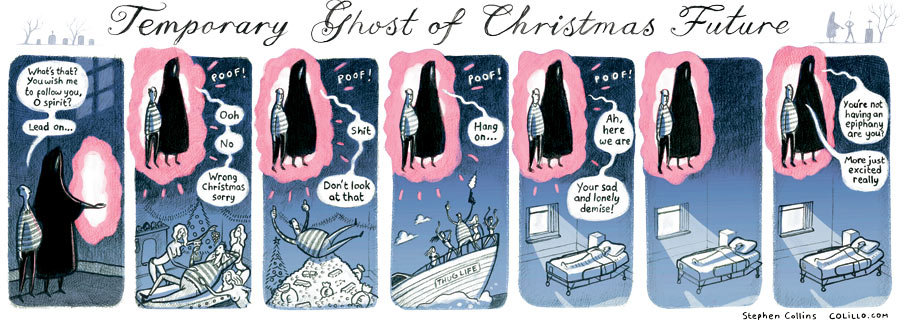

Charles Dickens at work. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In 1866 it was, said the Victorian actress Ellen Terry, "the thing that made me homesick for London".

For 20 years, a tuppenny weekly magazine run and edited by Charles Dickens was eagerly awaited by a readership who, each Wednesday, were given not only colourful reportage of the events of the day but also drip-fed instalments of what later became the writer's most famous books.

Modern academics hope the populist appeal of the journal – called Household Words when it began in 1850, then changed to All the Year Round in 1859 when Dickens dropped his publisher and went it alone – can be rekindled.

Volunteers have been invited to help bring all 1,101 editions into the digital age, making them accessible to an audience as wide as the 300,000 Victorians who bought the periodical weekly.

"The excitement in the sixties over each new Dickens can be understood only by people who experienced it at that time," Terry wrote in her autobiography. "Boys used to sell [it] in the streets, and they were often pursued by an eager crowd, for all the world as if they were carrying news of the 'latest winner'."

The bicentenary of the birth of Dickens is on 7 February 2012. The tiny team at the University of Buckingham hoped to have the journals online by then but, while the pages have been scanned, they now need to have the inevitable computer-made errors edited out – and for that only the human eye will do.

The sheer number of pages –30,000 – poses a problem when it comes to meeting the target date. So a call to the keyboard has gone out to all amateur copy editors with access to a computer.

"The machine-read transcripts all have to be corrected, but the cost would be substantial in these straitened times so we decided to open it up," said senior English lecturer at Buckingham, Dr John Drew. "But only 15% of the archive work was taken up, mostly by postgraduates and academics."

After having a letter published in the Guardian on Wednesday, more volunteers have come forward and almost 20% of the journals are now being edited.

In their day, these were phenomenally respected journals, carrying instalments of Great Expectations, Hard Times, North and South and The Woman in White, as well as poetry, investigative journalism, travel writing, popular science, history and political comment.

The three billion words contain both historical gems detailing the lives, the social problems and the politics of the Victorians, and a literary treasure trove of the works of Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, George Sala and Elizabeth Gaskell.

There was also unknown talent. "Wilkie Collins's brother Charlie wrote some extraordinarily vivid eyewitness accounts. He is an individual lost by history, although he married Dickens's daughter and wrote much of the magazine for the first 10 years," said Drew.

"Dickens started out as a parliamentary reporter, and the Pickwick Papers was originally a book of sartorial and amusing sketches. The fact he was writing his fiction for a weekly magazine audience is one of the reasons Dickens has survived into modern times. It is very visual work, full of imagery that translated into TV and cinema in a way that Thackeray, say, never could."

But Dickens also pursued stories other newspapers wouldn't touch – not just the conditions in mills and factories and, one of his favourite themes, prisons, but also foreign stories. He commissioned Thomas Trollope, brother of Anthony, to provide extensive coverage of the massacres of the second Italian war of independence (April-July 1859) against the Austrian empire even as Britain sat, hamstrung by royal family loyalties, on the sidelines. Its graphic accounts contradicted much contemporaneous, politely neutral coverage. "I was editing those dispatches when on the news was the debate about going into Libya and it was so interesting to have the historical context," said Drew.

One of his own favourite passages is a less dramatic event, however. "It is a vigorous report that, while remaining completely unpatronising, nevertheless makes deeply uncomfortable reading. It says as much about our current values and attitudes as it does about Victorian love of eccentricity and the [so-called] grotesque," noted Drew.

Under the headline Pursuit of Cricket Under Difficulties, Dickens wrote: "I know that we English are an angular and eccentric people –a people that the great flat-iron of civilisation will take a long time smoothing all the puckers and wrinkles out of – but I was scarcely prepared for the following announcement that I saw the other day in a tobacconist's window near the Elephant and Castle: On Saturday, A Cricket Match will be played at the Rosemary Branch, Peckham Rye, between Eleven One-armed Men and Eleven One-legged Men.

"'Well, I have heard of eccentric things in my time,' thought I, 'but I think this beats them all. I know we are a robust muscular people, who require vigorous exercise, so that we would rather be fighting than doing nothing' … Such were my patriotic thoughts when I trudged down the Old Kent Road… and made my devious way to Peckham. Under swinging golden hams, golden gridirons, swaying concertinas (marked at a very low figure), past bundles of rusty fire-irons, dirty rolls of carpets, and corpulent, dusty feather-beds, past deserted-looking horse-troughs and suburban-looking inns, I took my pilgrim way to the not very blooming Rye of Peckham.

"The one-legged men were pretty well with the bat, but they were rather beaten when it came to fielding. There was a horrible Hogarthian fun about the way they stumped, trotted, and jolted after the ball. A converging rank of crutches and wooden legs tore down upon the ball from all sides while the one-armed men, wagging their hooks and stumps, rushed madly from wicket to wicket, fast for a 'oner', faster for 'a twoer'. A lean, droll, rather drunk fellow, in white trousers, was the wit of the one-leg party. 'Peggy' evidently rejoiced in the fact that he was the lamest man in the field, one leg being stiff from the hip downwards."

Dickens did not treat the game so much as a matter of science as an affair of pure fun.

To discover your own Victorian gems go to www.djo.org.uk, where you can register to edit an edition of your choice (no Dickens knowledge necessary), or help the project at www.buckingham.ac.uk/djo/donate.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Three billion words in great author's weekly magazine are giving academics a massive proofreading problem

Tracy McVeigh guardian.co.uk, Saturday 6 August 2011 22.28 BST

Charles Dickens at work. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In 1866 it was, said the Victorian actress Ellen Terry, "the thing that made me homesick for London".

For 20 years, a tuppenny weekly magazine run and edited by Charles Dickens was eagerly awaited by a readership who, each Wednesday, were given not only colourful reportage of the events of the day but also drip-fed instalments of what later became the writer's most famous books.

Modern academics hope the populist appeal of the journal – called Household Words when it began in 1850, then changed to All the Year Round in 1859 when Dickens dropped his publisher and went it alone – can be rekindled.

Volunteers have been invited to help bring all 1,101 editions into the digital age, making them accessible to an audience as wide as the 300,000 Victorians who bought the periodical weekly.

"The excitement in the sixties over each new Dickens can be understood only by people who experienced it at that time," Terry wrote in her autobiography. "Boys used to sell [it] in the streets, and they were often pursued by an eager crowd, for all the world as if they were carrying news of the 'latest winner'."

The bicentenary of the birth of Dickens is on 7 February 2012. The tiny team at the University of Buckingham hoped to have the journals online by then but, while the pages have been scanned, they now need to have the inevitable computer-made errors edited out – and for that only the human eye will do.

The sheer number of pages –30,000 – poses a problem when it comes to meeting the target date. So a call to the keyboard has gone out to all amateur copy editors with access to a computer.

"The machine-read transcripts all have to be corrected, but the cost would be substantial in these straitened times so we decided to open it up," said senior English lecturer at Buckingham, Dr John Drew. "But only 15% of the archive work was taken up, mostly by postgraduates and academics."

After having a letter published in the Guardian on Wednesday, more volunteers have come forward and almost 20% of the journals are now being edited.

In their day, these were phenomenally respected journals, carrying instalments of Great Expectations, Hard Times, North and South and The Woman in White, as well as poetry, investigative journalism, travel writing, popular science, history and political comment.

The three billion words contain both historical gems detailing the lives, the social problems and the politics of the Victorians, and a literary treasure trove of the works of Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, George Sala and Elizabeth Gaskell.

There was also unknown talent. "Wilkie Collins's brother Charlie wrote some extraordinarily vivid eyewitness accounts. He is an individual lost by history, although he married Dickens's daughter and wrote much of the magazine for the first 10 years," said Drew.

"Dickens started out as a parliamentary reporter, and the Pickwick Papers was originally a book of sartorial and amusing sketches. The fact he was writing his fiction for a weekly magazine audience is one of the reasons Dickens has survived into modern times. It is very visual work, full of imagery that translated into TV and cinema in a way that Thackeray, say, never could."

But Dickens also pursued stories other newspapers wouldn't touch – not just the conditions in mills and factories and, one of his favourite themes, prisons, but also foreign stories. He commissioned Thomas Trollope, brother of Anthony, to provide extensive coverage of the massacres of the second Italian war of independence (April-July 1859) against the Austrian empire even as Britain sat, hamstrung by royal family loyalties, on the sidelines. Its graphic accounts contradicted much contemporaneous, politely neutral coverage. "I was editing those dispatches when on the news was the debate about going into Libya and it was so interesting to have the historical context," said Drew.

One of his own favourite passages is a less dramatic event, however. "It is a vigorous report that, while remaining completely unpatronising, nevertheless makes deeply uncomfortable reading. It says as much about our current values and attitudes as it does about Victorian love of eccentricity and the [so-called] grotesque," noted Drew.

Under the headline Pursuit of Cricket Under Difficulties, Dickens wrote: "I know that we English are an angular and eccentric people –a people that the great flat-iron of civilisation will take a long time smoothing all the puckers and wrinkles out of – but I was scarcely prepared for the following announcement that I saw the other day in a tobacconist's window near the Elephant and Castle: On Saturday, A Cricket Match will be played at the Rosemary Branch, Peckham Rye, between Eleven One-armed Men and Eleven One-legged Men.

"'Well, I have heard of eccentric things in my time,' thought I, 'but I think this beats them all. I know we are a robust muscular people, who require vigorous exercise, so that we would rather be fighting than doing nothing' … Such were my patriotic thoughts when I trudged down the Old Kent Road… and made my devious way to Peckham. Under swinging golden hams, golden gridirons, swaying concertinas (marked at a very low figure), past bundles of rusty fire-irons, dirty rolls of carpets, and corpulent, dusty feather-beds, past deserted-looking horse-troughs and suburban-looking inns, I took my pilgrim way to the not very blooming Rye of Peckham.

"The one-legged men were pretty well with the bat, but they were rather beaten when it came to fielding. There was a horrible Hogarthian fun about the way they stumped, trotted, and jolted after the ball. A converging rank of crutches and wooden legs tore down upon the ball from all sides while the one-armed men, wagging their hooks and stumps, rushed madly from wicket to wicket, fast for a 'oner', faster for 'a twoer'. A lean, droll, rather drunk fellow, in white trousers, was the wit of the one-leg party. 'Peggy' evidently rejoiced in the fact that he was the lamest man in the field, one leg being stiff from the hip downwards."

Dickens did not treat the game so much as a matter of science as an affair of pure fun.

To discover your own Victorian gems go to www.djo.org.uk, where you can register to edit an edition of your choice (no Dickens knowledge necessary), or help the project at www.buckingham.ac.uk/djo/donate.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Charles Dickens

Re: Charles Dickens

Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst, Charles Dickens: A Life by Claire Tomalin – reviews

Two hundred years after Charles Dickens's birth, his restless, blazing life still fascinates

Jenny Uglow

guardian.co.uk, Friday 7 October 2011 22.54 BST

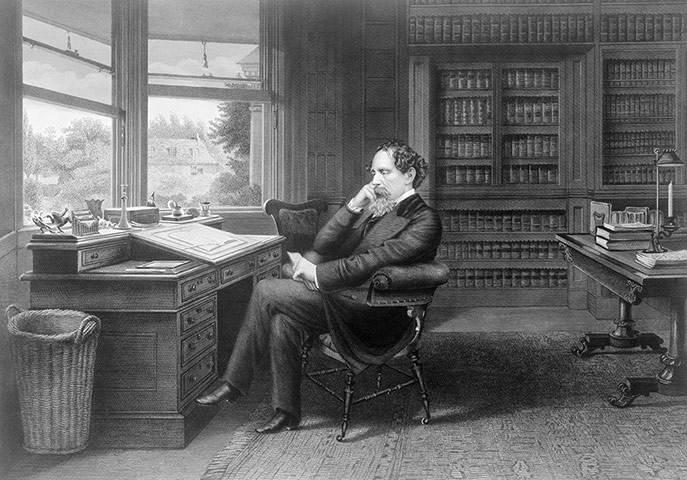

Charles Dickens. Photograph: Epics/Getty Images

Both these books give a powerful impression of how exhilarating, and how exhausting, it must be to write about Dickens, let alone to be Dickens. Sketches, stories, plays, journals and scripts for triumphant readings spill from his pen, as well as his great novels; letters, notes and diaries run into volumes; criticism begins in his lifetime and articles, biographies and studies now overflow the library shelves; vehement arguments about his character, his life and his genius – or lack of it – still echo loudly, 200 years after he was born.

Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist

by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

In Claire Tomalin's onward-driving, hypnotically vivid life of the "inimitable" Dickens (Charles Dickens: A Life,Viking), the words "restless", "hurrying", "busy", hum through the pages. On one holiday at Gad's Hill, she notes, "he tried to be lazy". But there was a novel to write, Great Expectations, and six readings to prepare, and then all his work was set askew by the death of his tour manager, and of his brother-in-law and old friend Henry Austin. Being lazy was not possible. He was active even when writing. His daughter Mamie famously described him writing, "busily and rapidly at his desk", then suddenly jumping from his chair, rushing to a mirror and making "extraordinary facial contortions", before returning rapidly again to his desk and writing furiously for a few moments, then dashing to the mirror again. "The facial pantomime was resumed, and then turning toward, but evidently not seeing me he began talking rapidly in a low voice."

As a relief from writing he would walk for miles, extremely fast. He could not keep still, and wherever he moved, he collected friends, so that the pages of biographies, like the bustling London streets he described so well, and like his novels with their varied, sharp-elbowed characters, are inevitably crowded with people. His talent for friendship is clear from his bachelor days, when he and his cronies went on long tramps, rides and river trips, and spent the evenings smoking, drinking and partying – "having a flare", as he put it.

Being with Dickens, is also to be with the illustrators Hablot Browne ("Phiz") and John Leech, with Macready and Wilkie Collins, with the actor Charles Fechter, who gave him the Swiss chalet he installed as a writing room at Gad's Hill, with the large, stammering George Dolby, who accompanied him tirelessly on his late reading tours, with Hans Christian Andersen, who outstayed his welcome – and countless others. But the great, central friendship, movingly described by Tomalin, was with John Forster. Although there were times of irritation, coolness and positive fallings out, Forster remained his informal literary agent, reader, adviser and confidant until the end, taking up the role of first biographer, with which Dickens had entrusted him, only days after the funeral in Westminster Abbey in June 1870.

Dickens met Forster in the mid 1830s, when both were in their 20s. In these years, in Tomalin's words, "his pursuit of various goals was so energetic, and he demonstrated such an ability to do so many different things at once, and fast, that even his search for a career had an aspect of genius". This period is the focus of Robert Douglas-Fairhurst's perceptive and original study, Becoming Dickens. He begins by asking us to imagine an alternative London, based on the steam-driven world of William Gibson's The Difference Engine, a novel itself being a sort of "difference engine", creating a fictional world.

The topical reference acknowledges the contemporary perspective from which we look at the novels and lives of the past, making narrative choices and judgments. The conceit also invites the possibility of alternative lives for Dickens himself, based on the different avenues he hurried down before he leapt into fame at the age of 25, first with Sketches by Boz and The Pickwick Papers, and then Oliver Twist. We see him as a reporter, struggling with shorthand, in Doctors' Commons and in parliament, as a would-be actor, stage-manager and playwright, as a lawyer's clerk and journalist. Douglas-Fairhurst cites Dickens's own words: "I know all these things have made me what I am." But in looking closely at key moments, such as Dickens as a small boy, lost in the city, or slaving in the blacking factory at the age of 12, he also plays with a range of "what ifs?", looking outward at the children Dickens might have been and at their fictional counterparts: Oliver Twist, Smike, Jo the crossing sweeper.

By the time of his first triumphs, both writers remind us, Dickens was already the father of a son, the first of his 10 children with Catherine Hogarth. Indeed, he seems to have been "married" in different ways to three Hogarth sisters; not only to Catherine, but to her younger sister Mary, who died suddenly in his arms in May 1837, causing him such grief that he demanded to be buried beside her; and to the even younger Georgina, who joined the household at 15 and remained his housekeeper and friend until his death.

Becoming Dickens shows how Dickens created "alternative lives for Mary Hogarth", in the idealised young women who die young, like Dora in David Copperfield or Little Nell. Tomalin also catches such fictional parallels but because she opts boldly for the cradle-to-grave story, we meet the novels as they fall, like patches of calm water in a rushing river. In her perceptive discussions of the fiction, the emphasis is strongly on the characters. Linking the inhabitants of Dickens's imagination to his life, she quotes the remarkable letter from Dostoevsky – who had read The Pickwick Papers and David Copperfield in prison. He visited Dickens in London and remembered their conversation: "There were two people in him, he told me, one who feels as he ought to feel and one who feels the opposite. From the one who feels the opposite I make my evil characters, from the one who feels as a man ought to feel I try to live my life. Only two people? I asked."

There are many instances of Dickens trying to live his life well. His intense concern for the poor and outcast is typified by the incident with which Tomalin opens her book, his intervention on behalf of Eliza Burgess in 1840, a servant girl accused of killing her newborn baby. Equally, she shows us the ruthless Dickens, the man with the "military" glint, so evident in his dealings with his publishers, who so often started as angels and ended as villains.

Most of all, he hated his own mistakes. When Maria Beadnell, the passion of his youth, contacted him in 1854, he was initially fascinated. Then they met. He found her fat, talkative and silly, punishing her as Flora in Little Dorrit, "overweight, greedy, a drinker, and garrulous to match". His feckless father and complacent mother, whom he blamed all his life for his blacking factory misery, and for pursuing him with their endless debts, were packed off to Devon and mocked as the Micawbers. The sons who disappointed him were sent to the colonies and then, it seems, forgotten. When his love for the young actress Ellen Ternan overwhelmed him, he turned viciously on Catherine and all who spoke up for her. This makes dark reading. Sad reading too, for Tomalin firmly upholds her conclusion in The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens, that Nelly, living quietly in France, bore Dickens a son, who died in infancy.

In the early 1860s Dickens's restlessness and anxiety reached a peak, taking him back and forth across the channel, probably to see Nelly, at least 68 times in three years. His last years were a blaze of physical and mental effort: what had been a walk, a stroll, a gallop, was now painful and difficult. In July 1864, when Our Mutual Friend was being serialised in monthly numbers, he told Forster, in an image full of yearning, that he had "a very mountain to climb before I shall see the open country of my work".

Even the accounts of his death have an unsettled, urgent feeling. Was he in Peckham with Nelly and rushed home to Gad's Hill unconscious in a hackney cab, to save his reputation? Or did he collapse in the dining room, talking incoherently, as Georgina Hogarth said? Georgina's account, although muddled in details, had the authentic oddity of Dickens. "Come and lie down," she told him. "Yes," he replied, as if quoting a novel of his own, "on the ground."

Charles Dickens: A Life is an intimate portrait despite its broad canvas. At times, I wished there were more space to follow his writerly relationships, or to explore aspects of his life outside the family, like his role as editor of Household Words and All the Year Round. But perhaps this desire is simply the result of Claire Tomalin's unrivalled talent for telling a story and keeping a reader enthralled: long as the book is, I wanted more.

Jenny Uglow's A Gambling Man is published by Faber.

Two hundred years after Charles Dickens's birth, his restless, blazing life still fascinates

Jenny Uglow

guardian.co.uk, Friday 7 October 2011 22.54 BST

Charles Dickens. Photograph: Epics/Getty Images

Both these books give a powerful impression of how exhilarating, and how exhausting, it must be to write about Dickens, let alone to be Dickens. Sketches, stories, plays, journals and scripts for triumphant readings spill from his pen, as well as his great novels; letters, notes and diaries run into volumes; criticism begins in his lifetime and articles, biographies and studies now overflow the library shelves; vehement arguments about his character, his life and his genius – or lack of it – still echo loudly, 200 years after he was born.

Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist

by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

In Claire Tomalin's onward-driving, hypnotically vivid life of the "inimitable" Dickens (Charles Dickens: A Life,Viking), the words "restless", "hurrying", "busy", hum through the pages. On one holiday at Gad's Hill, she notes, "he tried to be lazy". But there was a novel to write, Great Expectations, and six readings to prepare, and then all his work was set askew by the death of his tour manager, and of his brother-in-law and old friend Henry Austin. Being lazy was not possible. He was active even when writing. His daughter Mamie famously described him writing, "busily and rapidly at his desk", then suddenly jumping from his chair, rushing to a mirror and making "extraordinary facial contortions", before returning rapidly again to his desk and writing furiously for a few moments, then dashing to the mirror again. "The facial pantomime was resumed, and then turning toward, but evidently not seeing me he began talking rapidly in a low voice."

As a relief from writing he would walk for miles, extremely fast. He could not keep still, and wherever he moved, he collected friends, so that the pages of biographies, like the bustling London streets he described so well, and like his novels with their varied, sharp-elbowed characters, are inevitably crowded with people. His talent for friendship is clear from his bachelor days, when he and his cronies went on long tramps, rides and river trips, and spent the evenings smoking, drinking and partying – "having a flare", as he put it.

Being with Dickens, is also to be with the illustrators Hablot Browne ("Phiz") and John Leech, with Macready and Wilkie Collins, with the actor Charles Fechter, who gave him the Swiss chalet he installed as a writing room at Gad's Hill, with the large, stammering George Dolby, who accompanied him tirelessly on his late reading tours, with Hans Christian Andersen, who outstayed his welcome – and countless others. But the great, central friendship, movingly described by Tomalin, was with John Forster. Although there were times of irritation, coolness and positive fallings out, Forster remained his informal literary agent, reader, adviser and confidant until the end, taking up the role of first biographer, with which Dickens had entrusted him, only days after the funeral in Westminster Abbey in June 1870.

Dickens met Forster in the mid 1830s, when both were in their 20s. In these years, in Tomalin's words, "his pursuit of various goals was so energetic, and he demonstrated such an ability to do so many different things at once, and fast, that even his search for a career had an aspect of genius". This period is the focus of Robert Douglas-Fairhurst's perceptive and original study, Becoming Dickens. He begins by asking us to imagine an alternative London, based on the steam-driven world of William Gibson's The Difference Engine, a novel itself being a sort of "difference engine", creating a fictional world.

The topical reference acknowledges the contemporary perspective from which we look at the novels and lives of the past, making narrative choices and judgments. The conceit also invites the possibility of alternative lives for Dickens himself, based on the different avenues he hurried down before he leapt into fame at the age of 25, first with Sketches by Boz and The Pickwick Papers, and then Oliver Twist. We see him as a reporter, struggling with shorthand, in Doctors' Commons and in parliament, as a would-be actor, stage-manager and playwright, as a lawyer's clerk and journalist. Douglas-Fairhurst cites Dickens's own words: "I know all these things have made me what I am." But in looking closely at key moments, such as Dickens as a small boy, lost in the city, or slaving in the blacking factory at the age of 12, he also plays with a range of "what ifs?", looking outward at the children Dickens might have been and at their fictional counterparts: Oliver Twist, Smike, Jo the crossing sweeper.

By the time of his first triumphs, both writers remind us, Dickens was already the father of a son, the first of his 10 children with Catherine Hogarth. Indeed, he seems to have been "married" in different ways to three Hogarth sisters; not only to Catherine, but to her younger sister Mary, who died suddenly in his arms in May 1837, causing him such grief that he demanded to be buried beside her; and to the even younger Georgina, who joined the household at 15 and remained his housekeeper and friend until his death.

Becoming Dickens shows how Dickens created "alternative lives for Mary Hogarth", in the idealised young women who die young, like Dora in David Copperfield or Little Nell. Tomalin also catches such fictional parallels but because she opts boldly for the cradle-to-grave story, we meet the novels as they fall, like patches of calm water in a rushing river. In her perceptive discussions of the fiction, the emphasis is strongly on the characters. Linking the inhabitants of Dickens's imagination to his life, she quotes the remarkable letter from Dostoevsky – who had read The Pickwick Papers and David Copperfield in prison. He visited Dickens in London and remembered their conversation: "There were two people in him, he told me, one who feels as he ought to feel and one who feels the opposite. From the one who feels the opposite I make my evil characters, from the one who feels as a man ought to feel I try to live my life. Only two people? I asked."

There are many instances of Dickens trying to live his life well. His intense concern for the poor and outcast is typified by the incident with which Tomalin opens her book, his intervention on behalf of Eliza Burgess in 1840, a servant girl accused of killing her newborn baby. Equally, she shows us the ruthless Dickens, the man with the "military" glint, so evident in his dealings with his publishers, who so often started as angels and ended as villains.

Most of all, he hated his own mistakes. When Maria Beadnell, the passion of his youth, contacted him in 1854, he was initially fascinated. Then they met. He found her fat, talkative and silly, punishing her as Flora in Little Dorrit, "overweight, greedy, a drinker, and garrulous to match". His feckless father and complacent mother, whom he blamed all his life for his blacking factory misery, and for pursuing him with their endless debts, were packed off to Devon and mocked as the Micawbers. The sons who disappointed him were sent to the colonies and then, it seems, forgotten. When his love for the young actress Ellen Ternan overwhelmed him, he turned viciously on Catherine and all who spoke up for her. This makes dark reading. Sad reading too, for Tomalin firmly upholds her conclusion in The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens, that Nelly, living quietly in France, bore Dickens a son, who died in infancy.

In the early 1860s Dickens's restlessness and anxiety reached a peak, taking him back and forth across the channel, probably to see Nelly, at least 68 times in three years. His last years were a blaze of physical and mental effort: what had been a walk, a stroll, a gallop, was now painful and difficult. In July 1864, when Our Mutual Friend was being serialised in monthly numbers, he told Forster, in an image full of yearning, that he had "a very mountain to climb before I shall see the open country of my work".

Even the accounts of his death have an unsettled, urgent feeling. Was he in Peckham with Nelly and rushed home to Gad's Hill unconscious in a hackney cab, to save his reputation? Or did he collapse in the dining room, talking incoherently, as Georgina Hogarth said? Georgina's account, although muddled in details, had the authentic oddity of Dickens. "Come and lie down," she told him. "Yes," he replied, as if quoting a novel of his own, "on the ground."

Charles Dickens: A Life is an intimate portrait despite its broad canvas. At times, I wished there were more space to follow his writerly relationships, or to explore aspects of his life outside the family, like his role as editor of Household Words and All the Year Round. But perhaps this desire is simply the result of Claire Tomalin's unrivalled talent for telling a story and keeping a reader enthralled: long as the book is, I wanted more.

Jenny Uglow's A Gambling Man is published by Faber.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Charles Dickens

Re: Charles Dickens

Digested read: Bleak House by Charles Dickens

John Crace digests your second-favourite Dickens novel, according to the Guardian Books poll celebrating the bicentenary of the writer's birth

John Crace

guardian.co.uk, Thursday 10 November 2011 14.49 GMT

Patrick Kennedy as Richard and Carey Mulligan as Ada in the BBC adaptation of Bleak House. Photograph: Mike Hogan/BBC

London. Fog everywhere. And in the very heart of the fog, the Lord Chancellor's court where the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce drones on, the nature of its contestation long since lost to all parties, save to the lawyers who eagerly count the costs. Though on this day some progress is made as two young people are made wards of their uncle, John Jarndyce, who resides at Bleak House.

Bleak House

by Charles Dickens

Meanwhile in Lincolnshire My Lady Dedlock, some 20 years younger than her husband, Sir Leicester, is receiving the family lawyer, Mr Tulkinghorn, prior to her departure from the tedium of the country for Paris. He shows her an affidavit and My Lady blanches. "Who copied this?" she asks, before delicately fainting.

Oh silly me! I can't think what possessed me to think I was clever enough to write a first person narrative all about silly old me, but I've started so I might as well carry on. Where was I? Oh yes, affecting to be a great deal stupider than I am. I rather think you might find that quite annoying after a while. But then as I'm also consistently nice the whole time, you might find that annoying too. But I am getting ahead of myself. My name is Esther Summerson. My parents are unknown to me and my early years were spent with my godmother. After she died I was sent away to a school and six years on I received a letter – as you do – saying that a Mr John Jarndyce wanted me to be a companion to his niece and nephew.

How lovely Ada and Richard turned out to be, and after a brief interlude with the Jellybys so that the satirical Mr Dickens could make his social commentary about those who put the wellbeing of the peoples of the Borioboola-Gha before that of their own, we settled at Bleak House near St Albans. There we met our benefactor, the kind Mr Jarndyce, and his dear friend Mr Skimpole, whom even one as stupid as me began to think a parasite after he begged Richard and I to lend him some money. But that unpleasantness was soon forgotten as Richard and Ada fell in love with one another. "I think I will become a doctor," he said. "Though don't forget I will have lots of money when Jarndyce v Jarndyce is settled."

In Chancery, having noted My Lady Dedlock's interest, Mr Tulkinghorn is enquiring about the identity of the scrivener. He is a man called Nemo who has conveniently died in his lodgings. But how? Perhaps young Jo the crossing sweeper can help us. And who is Jo? Why he is the essence of Victorian pathos, the lowest of the low, unnoticed and unloved by society and yet the very symbol of purity and goodness. "He wuz wery good to me," Jo says in a manner some may find endearing. "I don't kno nuffink." And yet if he knows so little why is it that this mysterious woman of very obvious bearing is asking young Jo to show her the unmarked grave where Nemo is buried? Be assured that Mr Tulkinghorn's spies will find out. My, how slow and convoluted the story has become, and still so many minor characters to introduce, for how else can Mr Dickens spin out the serialisation into 20 monthly parts? Yet if you want to hear of Miss Flite, the Snagsbys, Mrs Rouncewell, the Smallweeds, Krook and others, then I shall have to refer you to the original text: for now be content to meet Mr Guppy, the young lawyer, who has noticed an uncommon resemblance between My Lady Dedlock and Miss Esther Summerson.

It's me, Esther, again. Still cloyingly submissive you'll be pleased to know. Though not so much as to accept the impertinent offer of marriage from Mr Guppy, for – if it is not too much to hope – I rather think that in 500 pages or so I may be betrothed to the handsome and warm-hearted Dr Woodcourt who gave me some reason for encouragement before leaving the narrative after being nice to Young Jo. And so I spend my days happily, trying to keep dear Mr Jarndyce away from the east wind – my how he becomes agitated when the wind is so – and watching my dear, dear friends Ada and Richard fall ever more in love, though not without some anxiety on Mr Jarndyce's part for he feared that Richard was falling prey to his Jarndyce v Jarndyce obsession.

"Make no mistake, Richard," he warned, "No good will ever come from Chancery." Richard was not to be warned, though. Having decided perhaps that medicine was not for him, he had set his mind to being a lawyer so that he might better understand the case. Like Mr Jarndyce, I too feared for Richard's sanity, but as a mere woman what could I know of such matters? And besides, he and Ada were so very in love that I believed her goodness might triumph. Besides, there were other more exciting matters at hand, for Mr Jarndyce had taken us to stay with Mr Boythorn – pray, don't ask – and in church we had espied for the first time Sir Leicester and My Lady Dedlock. "How very much alike you and my Lady Dedlock look," said Ada. "Fie!" I replied. "Let's go and help a few poor people in the village."

What darkness descends. It is November. Filth and smoke hangs everywhere, clogging the very soul. In Chancery, the lawyers grow rich while their clients go mad, but Mr Tulkinghorn has intelligence that Nemo is a Captain Hawdon with whom My Lady Dedlock had an Affair before she married Sir Leicester, and from which union sprang the woman we now know as Miss Esther Summerson. All he needs are the letters in Krook's possession to prove it. But what is this? Krook has spontaneously combusted and the letters burnt with him. Who could have imagined such an end?

Not My Lady Dedlock, who fears her secret will soon be exposed. What will she do? First she will sack her French maid, Hortense. Why, you ask? Obviously because it is quite handy for later developments in the plot. And then she confesses all to Esther. "Truly I am the worst mother of all time! How can you forgive me, child? Yet we cannot see each other again!" she cries. What glorious melodrama! What exclamation marks! Yet Esther is not greatly disturbed, for she is a kindly soul and is well disposed to Mr Dickens. She understands the demands of writing to monthly deadlines so is prepared to overlook that some of My Lady Dedlock's story does not tally with the plotting of the early chapters. And so, dear reader, should you.

I must confess that the news I was My Lady Dedlock's bastard took me somewhat by surprise at first but I quickly shrugged it off after telling my benefactor, Mr Jarndyce, who also counselled me to keep my silence. Besides which, much of my time was taken with nursing Young Jo who was suffering from smallpox. "I don't kno nuffink," he said before vanishing into the night, though not before infecting me. And so it was that I too succumbed to the vile illness and found myself quite without sight for a month, a cliff-hanger infinitely more effective in a serialisation than when you need only turn the page to find my sight restored.

My face, though, was quite disfigured, but such is my easygoing nature that I was not greatly upset. If I was to be ugly from now on, so be it. How could I complain when there were so many other people so much worse off than me? And yet my new found hideousness did cause Mr Jarndyce to offer me his hand in marriage, a kindness I was quite willing to accept though we both agreed to keep our arrangement secret because there was much else to occupy us. Richard had joined the Army with Trooper George and decided Mr Janrdyce was his implacable enemy. How it pained me to see him gripped by the curse of Chancery, still more so as Ada was so devoted to him and has married him in secret. And lo, if that wasn't Dr Woodcourt coming back from India?

Misery. Squalor. Tenements. Death. My Lady Dedlock is speeding to London. Why? It seems that the letters are not burnt and that Mr Tulkinghorn is planning to reveal her secret. But no! Can you hear the gunshots? Mr Tulkinghorn is lying dead. Who can have done such a deed? "I'm arresting you for murder, Trooper George," says Inspector Bucket.

"But I am innocent," he replies.

"I know," says Bucket, knowingly, "but I had to arrest you to lure out the real culprit."

"But it was not me either," cries My Lady Dedlock.

"I know that, too," says Bucket. "The murderer is none other than Hortense who was lodging in my home."

"None of this seems very likely," observes the reader.

"Forgive me," says Bucket. "I'm one of the first fictional cops and I haven't really got the hang of these police procedurals."

And my lords and ladies, right reverends and wrong reverends, Mr Tulkinghorn is not the only one lying dead. There on the street is Young Jo whose last words were, "I am wery symbolic, sir." Who will mourn him? Certainly not anyone in the 21st century!

What also of My Lady Dedlock? What choice does she have but to fly now that Bucket has told Sir Leicester of her secret? And what irony that Sir Leicester chooses this moment to have a stroke while declaring his forgiveness?

Back to little old me! I wasn't at all well after getting smallpox and my recovery wasn't much helped by the news my mother had gone missing. How poignant it was that she had gone looking for me and had dropped down dead next to the grave of her former lover! How sad I would have been, had not Dr Woodcourt declared he was not concerned about my deformity and Mr Jarndyce, seeing the honour of the good doctor's intentions, released me from my promise to him. And gave me £200 into the bargain. It was a bit disappointing that Richard died, but I suppose that was almost inevitable. As it was that Jarndyce v Jarndyce should finally be resolved with no one getting anything. Now seven years have passed and how happy I am that everyone still thinks I'm wonderful.

John Crace digests your second-favourite Dickens novel, according to the Guardian Books poll celebrating the bicentenary of the writer's birth

John Crace

guardian.co.uk, Thursday 10 November 2011 14.49 GMT

Patrick Kennedy as Richard and Carey Mulligan as Ada in the BBC adaptation of Bleak House. Photograph: Mike Hogan/BBC

London. Fog everywhere. And in the very heart of the fog, the Lord Chancellor's court where the case of Jarndyce and Jarndyce drones on, the nature of its contestation long since lost to all parties, save to the lawyers who eagerly count the costs. Though on this day some progress is made as two young people are made wards of their uncle, John Jarndyce, who resides at Bleak House.

Bleak House

by Charles Dickens

Meanwhile in Lincolnshire My Lady Dedlock, some 20 years younger than her husband, Sir Leicester, is receiving the family lawyer, Mr Tulkinghorn, prior to her departure from the tedium of the country for Paris. He shows her an affidavit and My Lady blanches. "Who copied this?" she asks, before delicately fainting.

Oh silly me! I can't think what possessed me to think I was clever enough to write a first person narrative all about silly old me, but I've started so I might as well carry on. Where was I? Oh yes, affecting to be a great deal stupider than I am. I rather think you might find that quite annoying after a while. But then as I'm also consistently nice the whole time, you might find that annoying too. But I am getting ahead of myself. My name is Esther Summerson. My parents are unknown to me and my early years were spent with my godmother. After she died I was sent away to a school and six years on I received a letter – as you do – saying that a Mr John Jarndyce wanted me to be a companion to his niece and nephew.

How lovely Ada and Richard turned out to be, and after a brief interlude with the Jellybys so that the satirical Mr Dickens could make his social commentary about those who put the wellbeing of the peoples of the Borioboola-Gha before that of their own, we settled at Bleak House near St Albans. There we met our benefactor, the kind Mr Jarndyce, and his dear friend Mr Skimpole, whom even one as stupid as me began to think a parasite after he begged Richard and I to lend him some money. But that unpleasantness was soon forgotten as Richard and Ada fell in love with one another. "I think I will become a doctor," he said. "Though don't forget I will have lots of money when Jarndyce v Jarndyce is settled."

In Chancery, having noted My Lady Dedlock's interest, Mr Tulkinghorn is enquiring about the identity of the scrivener. He is a man called Nemo who has conveniently died in his lodgings. But how? Perhaps young Jo the crossing sweeper can help us. And who is Jo? Why he is the essence of Victorian pathos, the lowest of the low, unnoticed and unloved by society and yet the very symbol of purity and goodness. "He wuz wery good to me," Jo says in a manner some may find endearing. "I don't kno nuffink." And yet if he knows so little why is it that this mysterious woman of very obvious bearing is asking young Jo to show her the unmarked grave where Nemo is buried? Be assured that Mr Tulkinghorn's spies will find out. My, how slow and convoluted the story has become, and still so many minor characters to introduce, for how else can Mr Dickens spin out the serialisation into 20 monthly parts? Yet if you want to hear of Miss Flite, the Snagsbys, Mrs Rouncewell, the Smallweeds, Krook and others, then I shall have to refer you to the original text: for now be content to meet Mr Guppy, the young lawyer, who has noticed an uncommon resemblance between My Lady Dedlock and Miss Esther Summerson.

It's me, Esther, again. Still cloyingly submissive you'll be pleased to know. Though not so much as to accept the impertinent offer of marriage from Mr Guppy, for – if it is not too much to hope – I rather think that in 500 pages or so I may be betrothed to the handsome and warm-hearted Dr Woodcourt who gave me some reason for encouragement before leaving the narrative after being nice to Young Jo. And so I spend my days happily, trying to keep dear Mr Jarndyce away from the east wind – my how he becomes agitated when the wind is so – and watching my dear, dear friends Ada and Richard fall ever more in love, though not without some anxiety on Mr Jarndyce's part for he feared that Richard was falling prey to his Jarndyce v Jarndyce obsession.

"Make no mistake, Richard," he warned, "No good will ever come from Chancery." Richard was not to be warned, though. Having decided perhaps that medicine was not for him, he had set his mind to being a lawyer so that he might better understand the case. Like Mr Jarndyce, I too feared for Richard's sanity, but as a mere woman what could I know of such matters? And besides, he and Ada were so very in love that I believed her goodness might triumph. Besides, there were other more exciting matters at hand, for Mr Jarndyce had taken us to stay with Mr Boythorn – pray, don't ask – and in church we had espied for the first time Sir Leicester and My Lady Dedlock. "How very much alike you and my Lady Dedlock look," said Ada. "Fie!" I replied. "Let's go and help a few poor people in the village."

What darkness descends. It is November. Filth and smoke hangs everywhere, clogging the very soul. In Chancery, the lawyers grow rich while their clients go mad, but Mr Tulkinghorn has intelligence that Nemo is a Captain Hawdon with whom My Lady Dedlock had an Affair before she married Sir Leicester, and from which union sprang the woman we now know as Miss Esther Summerson. All he needs are the letters in Krook's possession to prove it. But what is this? Krook has spontaneously combusted and the letters burnt with him. Who could have imagined such an end?

Not My Lady Dedlock, who fears her secret will soon be exposed. What will she do? First she will sack her French maid, Hortense. Why, you ask? Obviously because it is quite handy for later developments in the plot. And then she confesses all to Esther. "Truly I am the worst mother of all time! How can you forgive me, child? Yet we cannot see each other again!" she cries. What glorious melodrama! What exclamation marks! Yet Esther is not greatly disturbed, for she is a kindly soul and is well disposed to Mr Dickens. She understands the demands of writing to monthly deadlines so is prepared to overlook that some of My Lady Dedlock's story does not tally with the plotting of the early chapters. And so, dear reader, should you.

I must confess that the news I was My Lady Dedlock's bastard took me somewhat by surprise at first but I quickly shrugged it off after telling my benefactor, Mr Jarndyce, who also counselled me to keep my silence. Besides which, much of my time was taken with nursing Young Jo who was suffering from smallpox. "I don't kno nuffink," he said before vanishing into the night, though not before infecting me. And so it was that I too succumbed to the vile illness and found myself quite without sight for a month, a cliff-hanger infinitely more effective in a serialisation than when you need only turn the page to find my sight restored.

My face, though, was quite disfigured, but such is my easygoing nature that I was not greatly upset. If I was to be ugly from now on, so be it. How could I complain when there were so many other people so much worse off than me? And yet my new found hideousness did cause Mr Jarndyce to offer me his hand in marriage, a kindness I was quite willing to accept though we both agreed to keep our arrangement secret because there was much else to occupy us. Richard had joined the Army with Trooper George and decided Mr Janrdyce was his implacable enemy. How it pained me to see him gripped by the curse of Chancery, still more so as Ada was so devoted to him and has married him in secret. And lo, if that wasn't Dr Woodcourt coming back from India?

Misery. Squalor. Tenements. Death. My Lady Dedlock is speeding to London. Why? It seems that the letters are not burnt and that Mr Tulkinghorn is planning to reveal her secret. But no! Can you hear the gunshots? Mr Tulkinghorn is lying dead. Who can have done such a deed? "I'm arresting you for murder, Trooper George," says Inspector Bucket.

"But I am innocent," he replies.

"I know," says Bucket, knowingly, "but I had to arrest you to lure out the real culprit."

"But it was not me either," cries My Lady Dedlock.

"I know that, too," says Bucket. "The murderer is none other than Hortense who was lodging in my home."

"None of this seems very likely," observes the reader.

"Forgive me," says Bucket. "I'm one of the first fictional cops and I haven't really got the hang of these police procedurals."

And my lords and ladies, right reverends and wrong reverends, Mr Tulkinghorn is not the only one lying dead. There on the street is Young Jo whose last words were, "I am wery symbolic, sir." Who will mourn him? Certainly not anyone in the 21st century!

What also of My Lady Dedlock? What choice does she have but to fly now that Bucket has told Sir Leicester of her secret? And what irony that Sir Leicester chooses this moment to have a stroke while declaring his forgiveness?

Back to little old me! I wasn't at all well after getting smallpox and my recovery wasn't much helped by the news my mother had gone missing. How poignant it was that she had gone looking for me and had dropped down dead next to the grave of her former lover! How sad I would have been, had not Dr Woodcourt declared he was not concerned about my deformity and Mr Jarndyce, seeing the honour of the good doctor's intentions, released me from my promise to him. And gave me £200 into the bargain. It was a bit disappointing that Richard died, but I suppose that was almost inevitable. As it was that Jarndyce v Jarndyce should finally be resolved with no one getting anything. Now seven years have passed and how happy I am that everyone still thinks I'm wonderful.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Charles Dickens

Re: Charles Dickens

A Tale of Two Cities- CD.

riverdp

The Guardian

10 November 2011 4:45PM

Embodiment of Dickensian ideals

What does Dickens and his novels embody? What makes them significant and powerful? For myself it is the belief in human goodness, the worthiness of sacrifice made for others and the weakness and fraility of human character - yet also the power we have within us as human beings to redeem ourselves, when we have the will to do so.

Or at least that's what Sydney Carton demonstrates in A Tale of Two Cities. He has tasted bitterness of life, suffers self-doubt and knows he has failed himself. An all-round disappointer is he. Besides, he is not innocent or innately good or kind like most Dickensian protagonists (that, though, makes him more interesting). Then again, somehow, because he is so unlike other protagonists that his journey of redemption is made more moving.

Dickens may seem simplistic and naive at times in his belief in human goodness, but the powerful and poignant way in which he expresses it , or rather, passionately expounds it, cannot be denied.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Charles Dickens

Re: Charles Dickens

Why A Christmas Carol was a flop for Dickens

An instant hit that is still drawing crowds a century-and-a-half on, the book brought its author scant rewards

Bah humbug ... Disney's A Christmas Carol

Earlier last month, Disney's A Christmas Carol grossed £1.9m on opening weekend in the UK, and $31m (£19m) in the US. The Observer's Philip French called this latest version of Dickens's Christmas classic "faithfully rendered and extremely frightening", while the New York Times's AO Scott praised Robert Zemeckis's script for retaining much of the "formal diction and moral concern" of the original. On both sides of the Atlantic, it was a triumphant – and profitable – day for Dickens.

A Christmas Carol (Puffin Classics)

by Charles Dickens

What most people don't realise, though, is that one of the best-loved (and best-selling) tales in the history of English literature was, for its author, a grave financial disappointment.

Published by Chapman and Hall on 19 December 1843, A Christmas Carol was an immediate success with the public, selling out its initial print run of 6,000 copies by Christmas Eve. But the cost of producing the book, published on a commission arrangement between Dickens and Chapman and Hall, was so high that once the publishers had tabulated their expenses, there was very little left over for the author himself. The main reason: Dickens's own insistence on a lavish format for what was to become the most famous of his holiday books.

Dickens wanted A Christmas Carol to be a beautiful little gift book, and as such he stipulated the following requirements: a fancy binding stamped with gold lettering on the spine and front cover; gilded edges on the paper all around; four full-page, hand-coloured etchings and four woodcuts by John Leech; half-title and title pages printed in bright red and green; and hand-coloured green endpapers to match the green of the title page. For Dickens, there was a great deal of excitement and celebration over the arrival of his elaborate new work. "Such dinings," he wrote to his American friend, Cornelius Felton, "such dancings, such conjurings, such blind-man's huffings, such theatre-goings, such kissings-out of old years and kissings-in of new ones, never took place in these parts before."

The excitement, however, was soon to be checked. Upon examining preliminary copies of the Carol, Dickens decided that he disliked the green of the title pages, which had turned a drab olive, and found that the green from the endpapers smudged and dusted off when touched. Changes were immediately executed, and by 17 December, two days before the book's release, the publisher had produced new copies of the book with a red and blue title page, a blue half-title page, and yellow endpapers (which did not require hand colouring). These changes, coupled with a number of significant textual corrections, pleased the young author, who was optimistic about sales. "I am sure [the book] will do me a great deal of good," he wrote to his solicitor, Thomas Mitton, "and I hope it will sell, well." He set the price of the Carol at a reasonable 5s. to encourage the largest possible number of purchasers.

Dickens was ultimately elated with the public's overwhelming response. Thackeray famously called the book "a national benefit", Lord Jeffrey commended Dickens for prompting more beneficence than "all the pulpits and confessionals in Christendom", and contemporary readers showed their enthusiasm by storming Victorian book stalls with each additional print run. "But the truth," wrote his friend and literary adviser, John Forster, "was that the price charged ... was too little to remunerate [its] outlay."

When Dickens received the initial receipts of production and sale from Chapman and Hall, he found that after the deductions for printing, paper, drawing and engraving, steel plates, paper for plates, colouring, binding, incidentals and advertising and commission to the publishers, the "Balance of account to Mr Dickens's credit" was a mere £137. "I had set my heart and soul upon a Thousand, clear," he wrote to Forster. "What a wonderful thing it is, that such a great success should occasion me such intolerable anxiety and disappointment!" Even after the close of the following year and the sale of 15,000 copies, Dickens had still only received £726.

By February of 1844, less than two months after the Carol's appearance, there were at least eight theatrical versions of A Christmas Carol in production, and since then there have been literally hundreds more adaptations for stage, radio, television, and film. The manuscript of A Christmas Carol itself – one of the crown jewels of the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York – has now been digitised in its entirety, and is available for inspection by anyone across the globe, free of charge. Dickens would no doubt be delighted by this munificent online project, but it is no small irony that for this instantly classic Christmas tale of greed and beneficence, Dickens received none of the millions that Tiny Tim and Ebenezer Scrooge continue to generate every year.

An instant hit that is still drawing crowds a century-and-a-half on, the book brought its author scant rewards

Bah humbug ... Disney's A Christmas Carol

Earlier last month, Disney's A Christmas Carol grossed £1.9m on opening weekend in the UK, and $31m (£19m) in the US. The Observer's Philip French called this latest version of Dickens's Christmas classic "faithfully rendered and extremely frightening", while the New York Times's AO Scott praised Robert Zemeckis's script for retaining much of the "formal diction and moral concern" of the original. On both sides of the Atlantic, it was a triumphant – and profitable – day for Dickens.

A Christmas Carol (Puffin Classics)

by Charles Dickens

What most people don't realise, though, is that one of the best-loved (and best-selling) tales in the history of English literature was, for its author, a grave financial disappointment.

Published by Chapman and Hall on 19 December 1843, A Christmas Carol was an immediate success with the public, selling out its initial print run of 6,000 copies by Christmas Eve. But the cost of producing the book, published on a commission arrangement between Dickens and Chapman and Hall, was so high that once the publishers had tabulated their expenses, there was very little left over for the author himself. The main reason: Dickens's own insistence on a lavish format for what was to become the most famous of his holiday books.

Dickens wanted A Christmas Carol to be a beautiful little gift book, and as such he stipulated the following requirements: a fancy binding stamped with gold lettering on the spine and front cover; gilded edges on the paper all around; four full-page, hand-coloured etchings and four woodcuts by John Leech; half-title and title pages printed in bright red and green; and hand-coloured green endpapers to match the green of the title page. For Dickens, there was a great deal of excitement and celebration over the arrival of his elaborate new work. "Such dinings," he wrote to his American friend, Cornelius Felton, "such dancings, such conjurings, such blind-man's huffings, such theatre-goings, such kissings-out of old years and kissings-in of new ones, never took place in these parts before."

The excitement, however, was soon to be checked. Upon examining preliminary copies of the Carol, Dickens decided that he disliked the green of the title pages, which had turned a drab olive, and found that the green from the endpapers smudged and dusted off when touched. Changes were immediately executed, and by 17 December, two days before the book's release, the publisher had produced new copies of the book with a red and blue title page, a blue half-title page, and yellow endpapers (which did not require hand colouring). These changes, coupled with a number of significant textual corrections, pleased the young author, who was optimistic about sales. "I am sure [the book] will do me a great deal of good," he wrote to his solicitor, Thomas Mitton, "and I hope it will sell, well." He set the price of the Carol at a reasonable 5s. to encourage the largest possible number of purchasers.

Dickens was ultimately elated with the public's overwhelming response. Thackeray famously called the book "a national benefit", Lord Jeffrey commended Dickens for prompting more beneficence than "all the pulpits and confessionals in Christendom", and contemporary readers showed their enthusiasm by storming Victorian book stalls with each additional print run. "But the truth," wrote his friend and literary adviser, John Forster, "was that the price charged ... was too little to remunerate [its] outlay."

When Dickens received the initial receipts of production and sale from Chapman and Hall, he found that after the deductions for printing, paper, drawing and engraving, steel plates, paper for plates, colouring, binding, incidentals and advertising and commission to the publishers, the "Balance of account to Mr Dickens's credit" was a mere £137. "I had set my heart and soul upon a Thousand, clear," he wrote to Forster. "What a wonderful thing it is, that such a great success should occasion me such intolerable anxiety and disappointment!" Even after the close of the following year and the sale of 15,000 copies, Dickens had still only received £726.

By February of 1844, less than two months after the Carol's appearance, there were at least eight theatrical versions of A Christmas Carol in production, and since then there have been literally hundreds more adaptations for stage, radio, television, and film. The manuscript of A Christmas Carol itself – one of the crown jewels of the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York – has now been digitised in its entirety, and is available for inspection by anyone across the globe, free of charge. Dickens would no doubt be delighted by this munificent online project, but it is no small irony that for this instantly classic Christmas tale of greed and beneficence, Dickens received none of the millions that Tiny Tim and Ebenezer Scrooge continue to generate every year.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Charles Dickens

Re: Charles Dickens

Madly inventive, hilarious, sometimes cloying - quintessential Dickens

Martin Chuzzlewit- CD.

There was a time when the characters of Sairey Gamp and Seth Pecksniff were better known than, say, Fagin or Ms Havisham. Surprising to a modern viewer, maybe, but undoubtedly true. Mrs Gamp even had a type of umbrella named after her. She was a fat, drunken midwife from the pages of Martin Chuzzlewit whose most notable feature was a tendency to introduce into her conversation a mysterious person by the name of Mrs Harris whenever she wished to make remarks complimentary to herself or otherwise self-serving. Or maybe Mrs Harris serves to distract her from her own harsh existence: her once dissolute, abusive, now dead husband, and her only son, also expired. In any case, no reader can fail to be entertained by the supposed utterances of Mrs H., or forget the blood-chilling moment when Mrs Betsey Prig responds to one of Sairey's stories with the terrible words: "Bother Mrs Harris! [...] I don't believe there's no sich a person!", finally giving voice to what we all suspected, but wouldn't have had the heart to say. Mrs Gamp is also responsible for perhaps the greatest statement of self-assertion in literature: "Gamp is my name, and Gamp my nater". Not wholly comprehensible on a semantic level, maybe, but with a certain Zen profundity to it.

Martin Chuzzlewit is also home to Dickens's consummate hypocrite, Seth Pecksniff, supposed architect and real extorter of money under false pretences from gullible apprentices. For about the first two thirds of the novel, the Pecksniff chapters constitute the most sustained flight of venemous sarcasm in all literature: Dickens says the opposite of what he means regarding Pecksniff, dripping with irony in its purest form. Towards the end, Dickens does descend to simply denouncing Pecksniff, and throws in several passages of melodrama and sentiment as well (anything to do with the Pinch siblings is a case in point), but, hey, no one said he was perfect, and such lapses are characteristic of most of his work.

Martin Chuzzlewit isn't perfect, but it will be very clear to anyone reading it that at many points it is a work of clear and inarguable genius. A lot of the Victorian judgements of Dickens's works have been more or less reversed in modern views, but perhaps it's time we rediscovered why they found Gamp and Pecksniff so worthy of admiration.

wallacm5

The Guardian

Martin Chuzzlewit- CD.

There was a time when the characters of Sairey Gamp and Seth Pecksniff were better known than, say, Fagin or Ms Havisham. Surprising to a modern viewer, maybe, but undoubtedly true. Mrs Gamp even had a type of umbrella named after her. She was a fat, drunken midwife from the pages of Martin Chuzzlewit whose most notable feature was a tendency to introduce into her conversation a mysterious person by the name of Mrs Harris whenever she wished to make remarks complimentary to herself or otherwise self-serving. Or maybe Mrs Harris serves to distract her from her own harsh existence: her once dissolute, abusive, now dead husband, and her only son, also expired. In any case, no reader can fail to be entertained by the supposed utterances of Mrs H., or forget the blood-chilling moment when Mrs Betsey Prig responds to one of Sairey's stories with the terrible words: "Bother Mrs Harris! [...] I don't believe there's no sich a person!", finally giving voice to what we all suspected, but wouldn't have had the heart to say. Mrs Gamp is also responsible for perhaps the greatest statement of self-assertion in literature: "Gamp is my name, and Gamp my nater". Not wholly comprehensible on a semantic level, maybe, but with a certain Zen profundity to it.

Martin Chuzzlewit is also home to Dickens's consummate hypocrite, Seth Pecksniff, supposed architect and real extorter of money under false pretences from gullible apprentices. For about the first two thirds of the novel, the Pecksniff chapters constitute the most sustained flight of venemous sarcasm in all literature: Dickens says the opposite of what he means regarding Pecksniff, dripping with irony in its purest form. Towards the end, Dickens does descend to simply denouncing Pecksniff, and throws in several passages of melodrama and sentiment as well (anything to do with the Pinch siblings is a case in point), but, hey, no one said he was perfect, and such lapses are characteristic of most of his work.

Martin Chuzzlewit isn't perfect, but it will be very clear to anyone reading it that at many points it is a work of clear and inarguable genius. A lot of the Victorian judgements of Dickens's works have been more or less reversed in modern views, but perhaps it's time we rediscovered why they found Gamp and Pecksniff so worthy of admiration.

wallacm5

The Guardian

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Charles Dickens

Re: Charles Dickens

Hard Times, our times? A fairy tale for any time.

Charles Dickens is my favourite prose writer, bar none, and though I like parts of many of his other novels better, I'd pick this one as his best entire novel.

F.R.Leavis famously praised its "compression" and he was certainly on to something. Even the otherwise magnificent "Great Expectations" sags in the second half as the Compeyson mystery unfolds at the expense of the Pip story. "Hard Times" however, is as toughly constructed as a Coketown girder. Three books. Three storylines. One, well-told tale put together in gripping three-chapter installments.

It was written from necessity, to keep the periodical, "Household Words" solvent - but this is a real novelist's novel. Here was a man who knew, within reason, where this was all going from first to last page, writing and publishing as he went along. This is an astonishing achievement that only an artist at the very top of his game could pull-off. I have been lucky enough to hold/read Dickens"'original manuscript held in the National Art Library, and what is particularly fascinating are the blue, planning pages upon which he sketched out, chapter by chapter, the bold architecture of his tale. Not yet, not yet... he delays and delays the discovery of Stephen Blackpool until the moment of greatest dramatic impact. You also see the names of key players toyed with, alternatives scored through. This really is living evidence the writer at work.

Yet none of this would mattter were Dickens not so utterly brilliant within that framework. Beyond the satirical critique of utilitarianism, this is also a deeply poetic and "magical" book rooted, perhaps more than any of his other books, in his childhood reading of the "Arabian Nights". This fairy-tale quality is most keenly shown perhaps in his villains.The drained, bloodless Bitzer, the witch Mrs. Sparsit - who seems to move around as if sat upon a broomstick- and the bored, lanquid devil himself, James Harthouse.

The heroines are also Dickens' best... the elemental goodness of Sissy Jupe and the troubled, complex Louisa are well rounded, credible women and even the more stereotypical Blackpool and Slackbridge are always interesting. We rejoice at the deflation of the crass hypocrite Bounderby and are ulimately left strangely sympathetic to Gradgrind.

There are so many standout moments within the writing. The mad, nodding elephant heads of the great beam-engines, the sparks in the fire of Louisa and Tom's nursery, the fine tobacco and easy manners with which Harthouse causes the whelp to betray his sister, the star at the top of Hell shaft. My personal favourite is the soaking and bedraggling of Mrs. Sparsit as he crashes through the woods and rain, picking-up various caterpillars along the way, as she desperately tries to overhear the fall of Louisa; a perfect blend of comedy and high drama.

Unfortunately, we now live in an age where the Gradgrinds have the whip hand again. The only game is the free market, the only line, the bottom line of profit but Dickens remains there to warn of us of the "muddle" that inevitably results from this idiocy and to point out to us that there is also a "wisdom of the heart".

The final word really belongs to the Dickens' cypher, Sleary, the Circus Master. "People mutht be amused." In this novel we are not only amused, but shown - through the shining figure of Sissy and the illuminated loyalty and selfless stoicism of Rachel - that there is always a better way of living.

pinkroom

The Guardian

Charles Dickens is my favourite prose writer, bar none, and though I like parts of many of his other novels better, I'd pick this one as his best entire novel.

F.R.Leavis famously praised its "compression" and he was certainly on to something. Even the otherwise magnificent "Great Expectations" sags in the second half as the Compeyson mystery unfolds at the expense of the Pip story. "Hard Times" however, is as toughly constructed as a Coketown girder. Three books. Three storylines. One, well-told tale put together in gripping three-chapter installments.

It was written from necessity, to keep the periodical, "Household Words" solvent - but this is a real novelist's novel. Here was a man who knew, within reason, where this was all going from first to last page, writing and publishing as he went along. This is an astonishing achievement that only an artist at the very top of his game could pull-off. I have been lucky enough to hold/read Dickens"'original manuscript held in the National Art Library, and what is particularly fascinating are the blue, planning pages upon which he sketched out, chapter by chapter, the bold architecture of his tale. Not yet, not yet... he delays and delays the discovery of Stephen Blackpool until the moment of greatest dramatic impact. You also see the names of key players toyed with, alternatives scored through. This really is living evidence the writer at work.

Yet none of this would mattter were Dickens not so utterly brilliant within that framework. Beyond the satirical critique of utilitarianism, this is also a deeply poetic and "magical" book rooted, perhaps more than any of his other books, in his childhood reading of the "Arabian Nights". This fairy-tale quality is most keenly shown perhaps in his villains.The drained, bloodless Bitzer, the witch Mrs. Sparsit - who seems to move around as if sat upon a broomstick- and the bored, lanquid devil himself, James Harthouse.

The heroines are also Dickens' best... the elemental goodness of Sissy Jupe and the troubled, complex Louisa are well rounded, credible women and even the more stereotypical Blackpool and Slackbridge are always interesting. We rejoice at the deflation of the crass hypocrite Bounderby and are ulimately left strangely sympathetic to Gradgrind.

There are so many standout moments within the writing. The mad, nodding elephant heads of the great beam-engines, the sparks in the fire of Louisa and Tom's nursery, the fine tobacco and easy manners with which Harthouse causes the whelp to betray his sister, the star at the top of Hell shaft. My personal favourite is the soaking and bedraggling of Mrs. Sparsit as he crashes through the woods and rain, picking-up various caterpillars along the way, as she desperately tries to overhear the fall of Louisa; a perfect blend of comedy and high drama.

Unfortunately, we now live in an age where the Gradgrinds have the whip hand again. The only game is the free market, the only line, the bottom line of profit but Dickens remains there to warn of us of the "muddle" that inevitably results from this idiocy and to point out to us that there is also a "wisdom of the heart".

The final word really belongs to the Dickens' cypher, Sleary, the Circus Master. "People mutht be amused." In this novel we are not only amused, but shown - through the shining figure of Sissy and the illuminated loyalty and selfless stoicism of Rachel - that there is always a better way of living.

pinkroom

The Guardian

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Charles Dickens

Re: Charles Dickens

Stoic searches for a star

I cannot believe I am first to post a Review here. About a quarter of your poll rate it their favourite Dickens... about what I would have imagined. Not his warmest (David Copperfield) nor his funniest (The Pickwick Papers) nor his most skilfully constructed (Hard Times) nor even the greatest in imaginative scope (Bleak House or Little Dorrit) but this is the novel that - for whatever reason - Dickens seems to have invested his very heart and soul into, and very many readers over the years have responded positively to that. I recall attending a reading by Andrew Motion a couple of years back and he expressed the view that this was the nearest any novel had come to the level of one, single, continuous poem, and I on balance think he is probably right.

What an opening.

The flat, mournful landscape of the Kent Marshes, the poor orphan boy, alone in the churchyard visiting the graves of his parents and lost little brothers when wham, the escaped convict Magwitch emerges from nowhere to terrorise the child into helping him. We then meet his living family , such as it is, similarly terrorised by his sister, Mrs Joe and their Christmas visitors, the silly Mr. Wopsle and the puffed-up humbug, Uncle Pumblechook. Typical Dickens; the blending of searing psychological realism with the wildly larger than life.

The Magwitch story done, and seemingly dusted, we begin the dark, twisty fairy-tale at Satis House that will leave Pip - and Estella - strangely dissatisfied forever. It is this aspect of the book that is the most profoundly poetic. Where "David Copperfield" viewed life from one side of middle-age as essentially hopeful, this second semi-autobiography takes a bleaker view; maybe there are no happy endings for emotionally crippled childhoods.

The re-appearance of Magwitch takes place more or less right in the middle of the novel and strangely proves to be the making of Pip.He grows into a wiser/better man as he strives to save Magwitch whilst losing Estella.The detective story developed at this point seems clumsy by modern standards but, along with his pal Wilkie Collins, Dickens was actually inventing an entire genre here.