How to be a woman

2 posters

Page 1 of 1

How to be a woman

How to be a woman

How to Be a Woman by Caitlin Moran – review

The award-winning columnist argues for less self-flagellation and more fun in her witty and astute manual for women

Miranda Sawyer The Observer, Sunday 26 June 2011

Hilarious: Caitlin Moran. Photograph: Martin Argles for the Guardian

Before we start, let's be clear: this is a great big hoot of a book. There are lines in it that will make you snort with laughter, situations so true to life that you will howl in recognition. It is very, very funny. So, you could read it just for that, for the entertainment value.

How To Be a Woman by Caitlin Moran

However, if you are female, and particularly if you are a female under 30, then, tucked around the jokes, Moran has provided you with a short, sharp, feminist manifesto. It's not academic: she doesn't present a research paper into gender differences in pay or interview women who have suffered domestic abuse. Instead, she uses her own life to examine the everyday niggles of everyday womanhood – hair removal, getting fat, tiny pants, expensive handbags – as well as the big stuff such as work, marriage and kids. She pins each topic out like a live, wriggling, sexist frog, ready for dissection. But, instead of scalpelling it into little bits, as, say, Germaine Greer would, Moran tickles it so hard that the frog has to beg for mercy and hop off.

Moran, a columnist for the Times, writes very quickly, so How To Be A Woman is timely. (In fact, if you're a regular reader of her columns, you'll be familiar with some of the book's topics – her wedding, the joy of bras, meeting Lady Gaga.) The book is also on point: like the best columnists, much of what she says is something you've already thought of, but not articulated, not quite. And, like I say, it's funny. Humour is, of course, the coolest, sharpest weapon in humanity's social armoury, and it's one that feminists, supposedly, lack. (Though we might mention Tina Fey, Joan Rivers, Nora Ephron…)

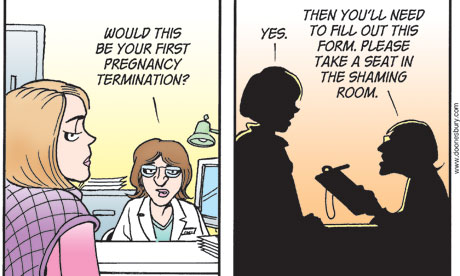

So, perhaps, the very fact that How To Be A Woman is so hilarious is its greatest strength. However, the parts of this book that I loved the most were actually the most serious. There are moments when Moran writes about her unconfident younger self that make you want to clutch that small person to you and say, "It will be all right". And her account of giving birth and – particularly – of her abortion are exceptionally moving. Not because they are feminist. But because they are true.

The book's structure loosely follows Moran's life, from child to thirtysomething, with the feminist analysis woven in between. If you wanted to be picky, there are a few occasions when this analysis doesn't quite work. Her conclusion about pornography is pretty woolly.

There are times when her test for sexism – equating it with a lack of politeness – will not work. But, for this reader at least, that is made up for by her seven-page rant about the delight of pubic hair that includes this observation: "Lying on a hammock, gently finger-combing your Wookie whilst staring up at the sky is one of the great pleasures of adulthood."

And Moran's final, simple argument, that there should be more of us, more, different women taking up more space and having more power in the world, is spot on. Why should women only be allowed to be seen and, particularly, heard if they are deemed acceptable enough to do so? Acceptable meaning "pretty and of the right age". You only need to go online, to read the blogs and tweets of the thousands of anonymous women out there to realise that we have as much to say, and can say it as cleverly and wittily, or as irritatingly and crassly, as men.

Moran has written for the Times since she was 17. She has won awards for her criticism and interviews. She is not an "ordinary" woman by any stretch of the imagination. However, the very nature of being female in the UK means that you share the same life architecture as most other women. Your life is structured in much the same way: to be blunt, you are sold the same shite. Brazilians, Botox, babies before you're too old: even if you know that you want none of these things, it can be hard not to be affected by an overbearing general atmosphere that tells you that you do. You must.

It can be hard not to be cowed.

The joy of this book is just that: the joy. What Moran is really arguing for is more female happiness. Women spend too much of their time worrying, beating themselves up, going along with time-wasting, restrictive, often expensive, sexist mores. The triumph of How To Be A Woman is that it adds to women's confidence. It reminds us that sexism, and all that is associated with it, is not only repressive, it is tedious and stupid. It is boring. Best give it a body swerve and get on with having fun.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

The award-winning columnist argues for less self-flagellation and more fun in her witty and astute manual for women

Miranda Sawyer The Observer, Sunday 26 June 2011

Hilarious: Caitlin Moran. Photograph: Martin Argles for the Guardian

Before we start, let's be clear: this is a great big hoot of a book. There are lines in it that will make you snort with laughter, situations so true to life that you will howl in recognition. It is very, very funny. So, you could read it just for that, for the entertainment value.

How To Be a Woman by Caitlin Moran

However, if you are female, and particularly if you are a female under 30, then, tucked around the jokes, Moran has provided you with a short, sharp, feminist manifesto. It's not academic: she doesn't present a research paper into gender differences in pay or interview women who have suffered domestic abuse. Instead, she uses her own life to examine the everyday niggles of everyday womanhood – hair removal, getting fat, tiny pants, expensive handbags – as well as the big stuff such as work, marriage and kids. She pins each topic out like a live, wriggling, sexist frog, ready for dissection. But, instead of scalpelling it into little bits, as, say, Germaine Greer would, Moran tickles it so hard that the frog has to beg for mercy and hop off.

Moran, a columnist for the Times, writes very quickly, so How To Be A Woman is timely. (In fact, if you're a regular reader of her columns, you'll be familiar with some of the book's topics – her wedding, the joy of bras, meeting Lady Gaga.) The book is also on point: like the best columnists, much of what she says is something you've already thought of, but not articulated, not quite. And, like I say, it's funny. Humour is, of course, the coolest, sharpest weapon in humanity's social armoury, and it's one that feminists, supposedly, lack. (Though we might mention Tina Fey, Joan Rivers, Nora Ephron…)

So, perhaps, the very fact that How To Be A Woman is so hilarious is its greatest strength. However, the parts of this book that I loved the most were actually the most serious. There are moments when Moran writes about her unconfident younger self that make you want to clutch that small person to you and say, "It will be all right". And her account of giving birth and – particularly – of her abortion are exceptionally moving. Not because they are feminist. But because they are true.

The book's structure loosely follows Moran's life, from child to thirtysomething, with the feminist analysis woven in between. If you wanted to be picky, there are a few occasions when this analysis doesn't quite work. Her conclusion about pornography is pretty woolly.

There are times when her test for sexism – equating it with a lack of politeness – will not work. But, for this reader at least, that is made up for by her seven-page rant about the delight of pubic hair that includes this observation: "Lying on a hammock, gently finger-combing your Wookie whilst staring up at the sky is one of the great pleasures of adulthood."

And Moran's final, simple argument, that there should be more of us, more, different women taking up more space and having more power in the world, is spot on. Why should women only be allowed to be seen and, particularly, heard if they are deemed acceptable enough to do so? Acceptable meaning "pretty and of the right age". You only need to go online, to read the blogs and tweets of the thousands of anonymous women out there to realise that we have as much to say, and can say it as cleverly and wittily, or as irritatingly and crassly, as men.

Moran has written for the Times since she was 17. She has won awards for her criticism and interviews. She is not an "ordinary" woman by any stretch of the imagination. However, the very nature of being female in the UK means that you share the same life architecture as most other women. Your life is structured in much the same way: to be blunt, you are sold the same shite. Brazilians, Botox, babies before you're too old: even if you know that you want none of these things, it can be hard not to be affected by an overbearing general atmosphere that tells you that you do. You must.

It can be hard not to be cowed.

The joy of this book is just that: the joy. What Moran is really arguing for is more female happiness. Women spend too much of their time worrying, beating themselves up, going along with time-wasting, restrictive, often expensive, sexist mores. The triumph of How To Be A Woman is that it adds to women's confidence. It reminds us that sexism, and all that is associated with it, is not only repressive, it is tedious and stupid. It is boring. Best give it a body swerve and get on with having fun.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: How to be a woman

Re: How to be a woman

Brazilians, Botox, babies before you're too old

No desire for any of the above.

I don't fancy that book at all, although I will admit to laughing at the pubic hair bit.

Nah Ville Sky Chick- Miss Whiplash

- Posts : 580

Join date : 2011-04-11

Re: How to be a woman

Re: How to be a woman

Feminism in the 21st century

Caitlin Moran writes about her body, Rachel Cusk dissects the aftermath of her divorce and Sylvia Walby addresses 'raunch culture'. What do their books reveal about feminism today?

Zoe Williams guardian.co.uk, Friday 24 June 2011 23.55 BST

Feminism is back ... Caitlin Moran and Germaine Greer have both attacked the elemental shame attached to being a woman, but where Greer was furious, Moran sloughs it off with exuberance. Photograph: Yuri Dojc/Getty Images

What is feminism? "Simply the belief that women should be as free as men . . . Are you a feminist? Hahaha. Of course you are."

Granta 115: The F Word

Caitlin Moran's How to be a Woman is firm, delightfully firm, on many things – heels (against), pubic waxing (against), abortion (for), the disadvantages of economising on sanitary products – and she is firm, she insists on, this simple definition of feminism. Feminism is just equality. Would a man be allowed to do it? Then so should you. Would a man feel bad about it? No? Then nor should you. Everything else – the pressure to be sisterly ("When did feminism become confused with Buddhism?"); the idea that we should be held to account, as feminists, for every possible ill that could befall the modern woman ("There's a whole generation of people who've confused 'feminism' with 'anything to do with women'") – all of that is just hassle in disguise.

Moran is right, it is simple: and yet, for such a simple message, its cultural penetration has been patchy, fluctuating and disappointing. People who like to sound the death knell for the ideology – it's remarkable even that such people still exist – point to the fact that young women tend not to describe themselves as feminists. There is a certain sour enjoyment from pointing out all the privileges that they owe to the sisterhood – the equal pay, the maternity leave – but I would query the importance of the self-description. One can promulgate the values of feminism quite effectively by just living them, by expecting fairness at work and at home, and young women are better at this, less surrendered, than anyone. Much more chilling for me was the recent debate around the Slut Walks. On mainstream television (Newsnight) the Conservative MP Louise Bagshawe said that the word "slut" could never be reclaimed, would always be a horrible word, because it "lionised promiscuity". Meanwhile, in mainstream print (the Sunday Times), columnist Minette Marrin wrote: "There is no universal human right to dress and behave like a sluttish streetwalker touting for sex, without occasionally being taken for one." These are not young women; they have been many years in this culture, without apparently encountering feminism's basic precepts. It ought to be taken as given, by now, that you can object to promiscuity generally, if you like, and I imagine this would be on faith grounds, but if you object to promiscuity in women, specifically, then you are barking up the wrong skirt. It ought to be obvious, beyond remarking, that a woman should be able to sleep with whom she wants, when she wants, as often as she wants, without danger and without shame. It surely should go without saying that being a prostitute and being raped are two different activities. The fact that so little progress has been made in the specific area of female sexuality is partly because of divisions within feminism – many of the boldest voices see the Slut business as a post-modern stunt, where sexual violence is used as a stalking horse to co-opt young women into hot pants and thence into the raunch culture that oppresses them further. Sylvia Walby, in her new book, The Future of Feminism, adjudicates on this magisterially. But divisions alone cannot account for this.

The best explanation I have read comes from Walby's account of the relevant "epistemic community", a term which is defined by Peter Haas as "a network of professionals with recognised expertise and competence in a particular domain . . . who have 1) a shared set of normative and principled beliefs . . . 2) shared causal beliefs, which are derived from their analysis . . . 3) a shared notion of validity and 4) a common policy enterprise". Such a community is the means by which ideas become practices and norms. The patriarchy isn't going to smash itself, to paraphrase Habermas (sort of), but nor is it so entrenched that it cannot be overturned by sustained, informed argumentation. This accounts for the huge advances that feminism has made – consider the daunting economic inequality that has been tackled in the past four decades, the astonishing speed of equal pay legislation across Europe and indeed the world. But it also accounts for the relatively meagre differences wrought in the arena of sexuality, because the epistemic community isn't there, the argument was never sustained. The last person to make any serious noise about female sexuality was Shere Hite; that was nearly 35 years ago. Orgasms were the stuff of the academy and of politics in the 1970s, but now, to go anywhere near that stuff would be a fast and effective way to sound like a crank.

I was expecting to find some tension between the dual purposes of memoir and polemic in Moran's book, but in fact, every word of the memoir is loaded with political importance. Female sexuality needs women to talk about sex, intelligently, out loud and in public (not just on Mumsnet) or it will forever remain a source of shame. Moran has been a columnist since she was a teenager, and while she has always been idiosyncratic, I'm not sure that I would have described her as radical. But there is iconoclasm lurking under every one-liner. I realised I have never read an account of someone's period starting. The closest I can even think of is Sarah Silverman's memoir about wetting the bed. I have never read a woman writing about wanking while fantasising about Chevy Chase (or anyone else; Chevy isn't the radical bit, here, although I do now see him in a whole new light). I have never read a sentence like this: "There is a great deal of pleasure to be had in a proper, furry muff . . . Lying in a hammock, gently finger-combing your Wookiee whilst staring up at the sky is one of the great pleasures of adulthood." I have read some of Moran's arguments about porn (though none so comically expressed); other insights are so shiny, neat, self-evidently right that it was like she was potting a snooker ball in my brain. This one about binge eating is an example:

"Overeating is the addiction choice of carers, and that's why it's come to be regarded as the lowest-ranking of all the addictions. It's a way of fucking yourself up whilst still remaining fully functional, because you have to. Fat people aren't indulging in the 'luxury' of their addiction making them useless, chaotic or a burden. Instead, they are slowly self-destructing in a way that doesn't inconvenience anyone. And that's why it's so often a woman's addiction of choice. All the quietly eating mums. All the KitKats in office drawers. All the unhappy moments, late at night, caught only in the fridge-light."

Structurally, the argument-told-as-memoir is not easy to pull off. A life told in comic episodes will not arrange itself neatly along feminist or any other ideological lines. The exigencies of the argument mean that the chapters have a very different emotional weight, so that the one on abortion is nothing like the thumping heart of the one on menstruation. The prose is columnistic, in that it's quite informal and very conversational; the sensation of having Moran in your house can be uncanny. But essentially, she's a comedian; her cadence is comic, her punctuation is comic, her wordplay is mischievous, and all this before you even touch on her observations. The irresistible pull of self-parody gives each paragraph a gravitational urgency. "I am a virgin and I don't play sport, or move heavy objects, or go anywhere or do anything, and so my body is this vast, sleeping, pale thing. There it is, standing awkwardly in the mirror, looking like it's waiting to receive bad news. It is the bad news." She can be funny in a terse, edgy way: "In those days, the music scene was much like Auschwitz. There were no birds. You couldn't find a woman making music for love nor money." She can be funny in a more expansive, absurdist way: "The problem with the word 'vagina' is that vaginas seem to be just straight-out bad luck. Only a masochist would want one, because only awful things happen to them. Vaginas get torn. Vaginas get 'examined'. Evidence is found in them. Serial killers leave things in them, to taunt Morse . . . No one wants one of those."

Page for page, my favourite chapter is "I Am in Love!" It's purportedly a story about falling in love with an unpleasant man, but I read it as a love letter to sisterhood, with a small "s"; a love letter to her actual sister, Caz. But in terms of changing the world, the momentous thing is to talk so freely about her body and its functions, in "a culture where", she says, "nearly everything female is still seen as squeam-inducing and/or weak". Germaine Greer, in a review that was warm but a bit salty, like sperm (sorry, I am essaying a new sexual openness – it is not as easy as it looks), ends: "More disconcerting is the way that Moran revisits themes that I have written thousands of words about, and even made TV documentaries about, the C-word and pornography for two, and restates my case in pretty much the same terms, with not the faintest suspicion that anyone has ever said any such things ever before." One can see how irritating this would be from Greer's perspective, and also how much it would have ruined Moran's momentum to have to finish everything pace Germaine. But what makes this book important is something unique to Caitlin Moran; she and Greer have both attacked the elemental shame attached to being a woman, but where Greer was furious, Moran sloughs it off with exuberance. There is a courage in this book that is born, not made, and not borrowed, either. It is vital in both senses.

In her prologue, Moran bemoans the fact that the women's revolution "had somehow shrunk down into a couple of increasingly small arguments, carried out between a couple of dozen feminist academics, in books that only feminist academics would read". Sylvia Walby, Unesco chair in gender research at Lancaster University, would probably concede that her audience is small, but would trenchantly contest that her arguments are small too. Hers is a densely written book, whose propositions proceed from one to another with the unforgiving directness of a quadratic equation. If you need a bit of breathing space, you can do it in your own time. It repays the effort, though, in the following ways. First, she addresses raunch culture or, if you prefer "post-feminism", which preoccupies and, I sometimes think, mires feminists, often creating discord between the second and third wave that needn't exist. "Raunch culture," Walby writes, "is bound up with the neoliberal turn, with its commercialised and competitive approach to intimacy. The alternative social democratic form is based on mutuality and equality. Hence, a celebration of innovation and experimentation in intimacy and sexuality, in the context of mutualism and equality, is aligned with feminism, while competitive commercialised sex is not." This is the message I take from that – though Walby, enemy of the broad brush stroke, would probably correct me: do what you want, girls, so long as you do want it. So long as it's in the service of your own sexual pleasure, and not to score some competitive advantage by manipulating the pleasure of someone else.

Walby takes great care to examine what we might call the disappearance of feminism, demonstrating that its change in nature has led to a change in visibility – far from having failed, this new low profile is actually testament to its "intersectionality". Again, I am putting this crudely, but feminism started out as a protest movement, so made a lot of noise; a process of persuasion has put feminists and their aims at or near the centre of governments, in many countries, so of course the protest element has been largely replaced by constructive, fruitful political engagement, which takes place with much less fanfare. She reminds us of so much that has been achieved, and alerts us to changes in gender equality architecture at a European level that would make Richard Littlejohn's eyes pop out. She explores the ways in which feminism can work with other aims, what the crossover is between feminism and environmentalism, and what the implications are of the financial crisis. But the strongest message of this book is that neoliberalism "makes the achievement of feminist goals more difficult. The increase in economic inequality and the decrease in the legitimacy of state action alter the context in which feminism makes its demands."

Her writing style is so restrained and so disciplined, that it takes some time to realise the impact of what she is saying: first, that feminism cannot thrive against a wider backdrop of inequality, and second, that feminists have a duty to more than just women. We are a battalion in a wider fight against the trend towards inequality. I found this a heartening and timely book, a proof against demoralisation, a warning against internecine splits. I also changed my mind about various things – unions, for one (they were somewhat slow off the mark in taking women seriously as a force worth allying with; but Walby shows these alliances were, and always will be, crucial); quotas, for another. It's interesting that Moran, from a totally different direction, arrives at roughly the same place – that quotas are a good thing. She says about sexism: "I don't really see it as men vs women at all. What I see, instead, is winner vs loser. Most sexism is down to men being accustomed to us being the losers. That's what the problem is. We just have bad status." The endpoint of both these very different books is that feminism has no meaning unless it's tied to a belief in equality overall.

The editor of Granta magazine, I dare to hope, when calling the latest edition"The F-Word" is referring to "female" rather than "feminist". If not, he has fallen into that GCSE syllogism: this book is about women; women are feminists; ergo this book is about feminism. Caroline Moorehead's "A Train in Winter", which describes the arrival of 230 French female resistance fighters in Birkenau, does seem to be attempting a feminist angle on the Holocaust at one point: "Block elders [were] for the most part German criminal prisoners who effectively collaborated with the SS and whose own survival depended on brutality. Their viciousness and vindictiveness was said to surpass by far that of their male counterparts." It's an interesting story, sensitively written, but a) this sounds suspiciously like one of those Daily Mail observations –"isn't it amazing that it's often women who bully other women?" – which, frankly, is not very feminist and b) I think it's pushing it to present the Nazis or any of their works as an outrage against women. Their brutality seems to have been fairly even-handed, or if it wasn't, the men surely suffered enough not to be presented as the winners of the atrocity. Julie Otsuka's "The Children" is a wonderful, mellow, seamless tale of first-generation Japanese immigrants to America. The most overtly feminist pieces include AS Byatt's "No Grls Alod. Insept Mom" (a notice attached to her five-year-old grandson's door), a short inventory of clubs she'd encountered that wouldn't allow girls or women. And Rachel Cusk's "Aftermath", a tantalising excerpt from her divorce memoir, which comes out next year.

Cusk's characterisation of feminism starts strangely: "Then again, the feminist is supposed to hate men. She scorns the physical and emotional servitude. She calls them the enemy." This isn't a sophisticated reading of feminism, so the author is clearly ascribing this belief to someone other than herself. But to whom? To mainstream society? To the past? To her soon-to-be ex-husband? I felt foolish not knowing, but then it struck me that it didn't matter. Why start a conversation about ideas with what a mistaken person thinks? Why not start with what you think? The next paragraph brings us, it seems, closer to Cusk's territory: "I suppose a feminist wouldn't get married. She wouldn't have a joint bank account or a house in joint names. She might not have children, either . . . I shouldn't have called myself a feminist because what I said didn't match with what I was."

Again, these definitions are curious. There is an argument that marriage reinforces the patriarchy, but there is no precept in feminism against sharing your wages. If you object to money or property held in common, that's not feminism, that's possessive individualism (the two are confused with one another, but not often on this subject). And a vision of feminism that involves eschewing reproduction altogether is like a vision of environmentalism that involves ending reproduction: it might work, but it would have the iatrogenic consequence of species suicide. This is not standard feminism; nobody would try to live by it. This is separatist feminism, the sort that makes young women say "I'm not a feminist".

This was written in fresh anger; Cusk is still very much in the throes of de-marriage. Aside from the confused versions of feminism – and the contortions do seem to be down to the splenetic mood – there are elements that are really indefensible from the husband's point of view, unless his return were to be added as an appendix. Cusk writes: "My husband believed that I had treated him monstrously. This belief of his couldn't be shaken; his whole world depended on it." It leaves the strong impression that she has plenty of beliefs of her own that she doesn't want shaken, and yet she has "come to hate stories. If someone were to ask me what disaster this was that had befallen my life, I might ask if they wanted the story or the truth." He, in this version, is blinded by his need for a narrative, while she plugs directly into the truth. It's a little bit partial. At one point, she describes their family situation – her husband gave up work to look after their daughters – as the result of her unwillingness to play the maternal role. This "cult, motherhood, was not a place where I could actually live. It reflected nothing about me: its literature and practices, its values, its codes of conduct, its aesthetic were not mine." And so she "conscripted" her husband into the care of the children. Less than a minute later (in reading time), a solicitor told her she would have to continue supporting her husband, financially, when they split up. "But he's a qualified lawyer, I said. And I'm just a writer. What I meant was, he's a man. And I'm just a woman . . . the solicitor raised her slender eyebrows, gave me a bitter little smile. Well, then he knew exactly what he was doing, she said." Whether she imputes that view to the solicitor or not, Cusk still wants it both ways: we're asked to imagine her ex as such a magnificent lawyer that he managed to make her feel as though she were conscripting him, when all along, they were working to his long-game. Her feelings of maternal alienation were, in this version, a confection of his, with the aim of divorcing her some years down the line and pinching half her salary. Not since we met Heathcliff have readers been presented with an anti-hero whose grudges are so intricately prosecuted.

But she's like a lion, depositing a trophy kill: you might feel a bit queasy about it from some angles, but there is so much meat here. "Help is dangerous because it exists outside the human economy: the only payment for help is gratitude," she writes, distilling that awkwardness between couples, especially between parents, the tightrope between being put-upon and beholden. There is something marvellous, even monumental, about her honesty, the unabashed importance she attaches to every event: "I went to Paris for two days with my husband, determined while I was there to have my hair cut in a French salon. Wasn't this what women did? Well, I wanted to be womanised; I wanted someone to restore to me my lost femininity. A male hairdresser cut off all my hair, giggling as he did it, amusing himself during a boring afternoon at the salon by giving a tired blank-faced mother of two something punky and nouvelle vague. Afterwards, I wandered in the Paris streets, anxiously catching my reflection in shop windows. Had a transformation occurred, or a defacement? I wasn't sure. My husband wasn't sure either. It seemed terrible that between us we couldn't establish the truth." There is a topnote of derision for her own sex ("wasn't this what women did?") that is a much more likely wellspring than Cusk's divorce for her suspicions over whether or not she is still a feminist. But sisterliness and feminism have never been interchangeable; they are less so now than ever, as the expansion of our choices has shaped us into so many varieties.

Her final paragraph is evocative to an almost supernatural degree: "I begin to notice, looking in through those imaginary brightly lit windows, that the people inside are looking out. I see the women, these wives and mothers, looking out. They seem happy enough, contented enough, capable enough: they are well dressed, attractive, standing around with their men and their children. Yet they look around, their mouths moving. It is as though they are missing something or wondering about something. I remember it so well, what it was to be one of them. Sometimes one of these glances will pass over me and our eyes will briefly meet. And I realise she can't see me, this woman whose eyes have locked with mine. It isn't that she doesn't want to, or is trying not to. It's just that inside it's so bright and outside it's so dark, and so she can't see out, can't see anything at all."

Cusk gazes at herself unblinkingly, and judges harshly what she sees. But to call herself not a feminist? Hahaha. Of course she's one.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Caitlin Moran writes about her body, Rachel Cusk dissects the aftermath of her divorce and Sylvia Walby addresses 'raunch culture'. What do their books reveal about feminism today?

Zoe Williams guardian.co.uk, Friday 24 June 2011 23.55 BST

Feminism is back ... Caitlin Moran and Germaine Greer have both attacked the elemental shame attached to being a woman, but where Greer was furious, Moran sloughs it off with exuberance. Photograph: Yuri Dojc/Getty Images

What is feminism? "Simply the belief that women should be as free as men . . . Are you a feminist? Hahaha. Of course you are."

Granta 115: The F Word

Caitlin Moran's How to be a Woman is firm, delightfully firm, on many things – heels (against), pubic waxing (against), abortion (for), the disadvantages of economising on sanitary products – and she is firm, she insists on, this simple definition of feminism. Feminism is just equality. Would a man be allowed to do it? Then so should you. Would a man feel bad about it? No? Then nor should you. Everything else – the pressure to be sisterly ("When did feminism become confused with Buddhism?"); the idea that we should be held to account, as feminists, for every possible ill that could befall the modern woman ("There's a whole generation of people who've confused 'feminism' with 'anything to do with women'") – all of that is just hassle in disguise.

Moran is right, it is simple: and yet, for such a simple message, its cultural penetration has been patchy, fluctuating and disappointing. People who like to sound the death knell for the ideology – it's remarkable even that such people still exist – point to the fact that young women tend not to describe themselves as feminists. There is a certain sour enjoyment from pointing out all the privileges that they owe to the sisterhood – the equal pay, the maternity leave – but I would query the importance of the self-description. One can promulgate the values of feminism quite effectively by just living them, by expecting fairness at work and at home, and young women are better at this, less surrendered, than anyone. Much more chilling for me was the recent debate around the Slut Walks. On mainstream television (Newsnight) the Conservative MP Louise Bagshawe said that the word "slut" could never be reclaimed, would always be a horrible word, because it "lionised promiscuity". Meanwhile, in mainstream print (the Sunday Times), columnist Minette Marrin wrote: "There is no universal human right to dress and behave like a sluttish streetwalker touting for sex, without occasionally being taken for one." These are not young women; they have been many years in this culture, without apparently encountering feminism's basic precepts. It ought to be taken as given, by now, that you can object to promiscuity generally, if you like, and I imagine this would be on faith grounds, but if you object to promiscuity in women, specifically, then you are barking up the wrong skirt. It ought to be obvious, beyond remarking, that a woman should be able to sleep with whom she wants, when she wants, as often as she wants, without danger and without shame. It surely should go without saying that being a prostitute and being raped are two different activities. The fact that so little progress has been made in the specific area of female sexuality is partly because of divisions within feminism – many of the boldest voices see the Slut business as a post-modern stunt, where sexual violence is used as a stalking horse to co-opt young women into hot pants and thence into the raunch culture that oppresses them further. Sylvia Walby, in her new book, The Future of Feminism, adjudicates on this magisterially. But divisions alone cannot account for this.

The best explanation I have read comes from Walby's account of the relevant "epistemic community", a term which is defined by Peter Haas as "a network of professionals with recognised expertise and competence in a particular domain . . . who have 1) a shared set of normative and principled beliefs . . . 2) shared causal beliefs, which are derived from their analysis . . . 3) a shared notion of validity and 4) a common policy enterprise". Such a community is the means by which ideas become practices and norms. The patriarchy isn't going to smash itself, to paraphrase Habermas (sort of), but nor is it so entrenched that it cannot be overturned by sustained, informed argumentation. This accounts for the huge advances that feminism has made – consider the daunting economic inequality that has been tackled in the past four decades, the astonishing speed of equal pay legislation across Europe and indeed the world. But it also accounts for the relatively meagre differences wrought in the arena of sexuality, because the epistemic community isn't there, the argument was never sustained. The last person to make any serious noise about female sexuality was Shere Hite; that was nearly 35 years ago. Orgasms were the stuff of the academy and of politics in the 1970s, but now, to go anywhere near that stuff would be a fast and effective way to sound like a crank.

I was expecting to find some tension between the dual purposes of memoir and polemic in Moran's book, but in fact, every word of the memoir is loaded with political importance. Female sexuality needs women to talk about sex, intelligently, out loud and in public (not just on Mumsnet) or it will forever remain a source of shame. Moran has been a columnist since she was a teenager, and while she has always been idiosyncratic, I'm not sure that I would have described her as radical. But there is iconoclasm lurking under every one-liner. I realised I have never read an account of someone's period starting. The closest I can even think of is Sarah Silverman's memoir about wetting the bed. I have never read a woman writing about wanking while fantasising about Chevy Chase (or anyone else; Chevy isn't the radical bit, here, although I do now see him in a whole new light). I have never read a sentence like this: "There is a great deal of pleasure to be had in a proper, furry muff . . . Lying in a hammock, gently finger-combing your Wookiee whilst staring up at the sky is one of the great pleasures of adulthood." I have read some of Moran's arguments about porn (though none so comically expressed); other insights are so shiny, neat, self-evidently right that it was like she was potting a snooker ball in my brain. This one about binge eating is an example:

"Overeating is the addiction choice of carers, and that's why it's come to be regarded as the lowest-ranking of all the addictions. It's a way of fucking yourself up whilst still remaining fully functional, because you have to. Fat people aren't indulging in the 'luxury' of their addiction making them useless, chaotic or a burden. Instead, they are slowly self-destructing in a way that doesn't inconvenience anyone. And that's why it's so often a woman's addiction of choice. All the quietly eating mums. All the KitKats in office drawers. All the unhappy moments, late at night, caught only in the fridge-light."

Structurally, the argument-told-as-memoir is not easy to pull off. A life told in comic episodes will not arrange itself neatly along feminist or any other ideological lines. The exigencies of the argument mean that the chapters have a very different emotional weight, so that the one on abortion is nothing like the thumping heart of the one on menstruation. The prose is columnistic, in that it's quite informal and very conversational; the sensation of having Moran in your house can be uncanny. But essentially, she's a comedian; her cadence is comic, her punctuation is comic, her wordplay is mischievous, and all this before you even touch on her observations. The irresistible pull of self-parody gives each paragraph a gravitational urgency. "I am a virgin and I don't play sport, or move heavy objects, or go anywhere or do anything, and so my body is this vast, sleeping, pale thing. There it is, standing awkwardly in the mirror, looking like it's waiting to receive bad news. It is the bad news." She can be funny in a terse, edgy way: "In those days, the music scene was much like Auschwitz. There were no birds. You couldn't find a woman making music for love nor money." She can be funny in a more expansive, absurdist way: "The problem with the word 'vagina' is that vaginas seem to be just straight-out bad luck. Only a masochist would want one, because only awful things happen to them. Vaginas get torn. Vaginas get 'examined'. Evidence is found in them. Serial killers leave things in them, to taunt Morse . . . No one wants one of those."

Page for page, my favourite chapter is "I Am in Love!" It's purportedly a story about falling in love with an unpleasant man, but I read it as a love letter to sisterhood, with a small "s"; a love letter to her actual sister, Caz. But in terms of changing the world, the momentous thing is to talk so freely about her body and its functions, in "a culture where", she says, "nearly everything female is still seen as squeam-inducing and/or weak". Germaine Greer, in a review that was warm but a bit salty, like sperm (sorry, I am essaying a new sexual openness – it is not as easy as it looks), ends: "More disconcerting is the way that Moran revisits themes that I have written thousands of words about, and even made TV documentaries about, the C-word and pornography for two, and restates my case in pretty much the same terms, with not the faintest suspicion that anyone has ever said any such things ever before." One can see how irritating this would be from Greer's perspective, and also how much it would have ruined Moran's momentum to have to finish everything pace Germaine. But what makes this book important is something unique to Caitlin Moran; she and Greer have both attacked the elemental shame attached to being a woman, but where Greer was furious, Moran sloughs it off with exuberance. There is a courage in this book that is born, not made, and not borrowed, either. It is vital in both senses.

In her prologue, Moran bemoans the fact that the women's revolution "had somehow shrunk down into a couple of increasingly small arguments, carried out between a couple of dozen feminist academics, in books that only feminist academics would read". Sylvia Walby, Unesco chair in gender research at Lancaster University, would probably concede that her audience is small, but would trenchantly contest that her arguments are small too. Hers is a densely written book, whose propositions proceed from one to another with the unforgiving directness of a quadratic equation. If you need a bit of breathing space, you can do it in your own time. It repays the effort, though, in the following ways. First, she addresses raunch culture or, if you prefer "post-feminism", which preoccupies and, I sometimes think, mires feminists, often creating discord between the second and third wave that needn't exist. "Raunch culture," Walby writes, "is bound up with the neoliberal turn, with its commercialised and competitive approach to intimacy. The alternative social democratic form is based on mutuality and equality. Hence, a celebration of innovation and experimentation in intimacy and sexuality, in the context of mutualism and equality, is aligned with feminism, while competitive commercialised sex is not." This is the message I take from that – though Walby, enemy of the broad brush stroke, would probably correct me: do what you want, girls, so long as you do want it. So long as it's in the service of your own sexual pleasure, and not to score some competitive advantage by manipulating the pleasure of someone else.

Walby takes great care to examine what we might call the disappearance of feminism, demonstrating that its change in nature has led to a change in visibility – far from having failed, this new low profile is actually testament to its "intersectionality". Again, I am putting this crudely, but feminism started out as a protest movement, so made a lot of noise; a process of persuasion has put feminists and their aims at or near the centre of governments, in many countries, so of course the protest element has been largely replaced by constructive, fruitful political engagement, which takes place with much less fanfare. She reminds us of so much that has been achieved, and alerts us to changes in gender equality architecture at a European level that would make Richard Littlejohn's eyes pop out. She explores the ways in which feminism can work with other aims, what the crossover is between feminism and environmentalism, and what the implications are of the financial crisis. But the strongest message of this book is that neoliberalism "makes the achievement of feminist goals more difficult. The increase in economic inequality and the decrease in the legitimacy of state action alter the context in which feminism makes its demands."

Her writing style is so restrained and so disciplined, that it takes some time to realise the impact of what she is saying: first, that feminism cannot thrive against a wider backdrop of inequality, and second, that feminists have a duty to more than just women. We are a battalion in a wider fight against the trend towards inequality. I found this a heartening and timely book, a proof against demoralisation, a warning against internecine splits. I also changed my mind about various things – unions, for one (they were somewhat slow off the mark in taking women seriously as a force worth allying with; but Walby shows these alliances were, and always will be, crucial); quotas, for another. It's interesting that Moran, from a totally different direction, arrives at roughly the same place – that quotas are a good thing. She says about sexism: "I don't really see it as men vs women at all. What I see, instead, is winner vs loser. Most sexism is down to men being accustomed to us being the losers. That's what the problem is. We just have bad status." The endpoint of both these very different books is that feminism has no meaning unless it's tied to a belief in equality overall.

The editor of Granta magazine, I dare to hope, when calling the latest edition"The F-Word" is referring to "female" rather than "feminist". If not, he has fallen into that GCSE syllogism: this book is about women; women are feminists; ergo this book is about feminism. Caroline Moorehead's "A Train in Winter", which describes the arrival of 230 French female resistance fighters in Birkenau, does seem to be attempting a feminist angle on the Holocaust at one point: "Block elders [were] for the most part German criminal prisoners who effectively collaborated with the SS and whose own survival depended on brutality. Their viciousness and vindictiveness was said to surpass by far that of their male counterparts." It's an interesting story, sensitively written, but a) this sounds suspiciously like one of those Daily Mail observations –"isn't it amazing that it's often women who bully other women?" – which, frankly, is not very feminist and b) I think it's pushing it to present the Nazis or any of their works as an outrage against women. Their brutality seems to have been fairly even-handed, or if it wasn't, the men surely suffered enough not to be presented as the winners of the atrocity. Julie Otsuka's "The Children" is a wonderful, mellow, seamless tale of first-generation Japanese immigrants to America. The most overtly feminist pieces include AS Byatt's "No Grls Alod. Insept Mom" (a notice attached to her five-year-old grandson's door), a short inventory of clubs she'd encountered that wouldn't allow girls or women. And Rachel Cusk's "Aftermath", a tantalising excerpt from her divorce memoir, which comes out next year.

Cusk's characterisation of feminism starts strangely: "Then again, the feminist is supposed to hate men. She scorns the physical and emotional servitude. She calls them the enemy." This isn't a sophisticated reading of feminism, so the author is clearly ascribing this belief to someone other than herself. But to whom? To mainstream society? To the past? To her soon-to-be ex-husband? I felt foolish not knowing, but then it struck me that it didn't matter. Why start a conversation about ideas with what a mistaken person thinks? Why not start with what you think? The next paragraph brings us, it seems, closer to Cusk's territory: "I suppose a feminist wouldn't get married. She wouldn't have a joint bank account or a house in joint names. She might not have children, either . . . I shouldn't have called myself a feminist because what I said didn't match with what I was."

Again, these definitions are curious. There is an argument that marriage reinforces the patriarchy, but there is no precept in feminism against sharing your wages. If you object to money or property held in common, that's not feminism, that's possessive individualism (the two are confused with one another, but not often on this subject). And a vision of feminism that involves eschewing reproduction altogether is like a vision of environmentalism that involves ending reproduction: it might work, but it would have the iatrogenic consequence of species suicide. This is not standard feminism; nobody would try to live by it. This is separatist feminism, the sort that makes young women say "I'm not a feminist".

This was written in fresh anger; Cusk is still very much in the throes of de-marriage. Aside from the confused versions of feminism – and the contortions do seem to be down to the splenetic mood – there are elements that are really indefensible from the husband's point of view, unless his return were to be added as an appendix. Cusk writes: "My husband believed that I had treated him monstrously. This belief of his couldn't be shaken; his whole world depended on it." It leaves the strong impression that she has plenty of beliefs of her own that she doesn't want shaken, and yet she has "come to hate stories. If someone were to ask me what disaster this was that had befallen my life, I might ask if they wanted the story or the truth." He, in this version, is blinded by his need for a narrative, while she plugs directly into the truth. It's a little bit partial. At one point, she describes their family situation – her husband gave up work to look after their daughters – as the result of her unwillingness to play the maternal role. This "cult, motherhood, was not a place where I could actually live. It reflected nothing about me: its literature and practices, its values, its codes of conduct, its aesthetic were not mine." And so she "conscripted" her husband into the care of the children. Less than a minute later (in reading time), a solicitor told her she would have to continue supporting her husband, financially, when they split up. "But he's a qualified lawyer, I said. And I'm just a writer. What I meant was, he's a man. And I'm just a woman . . . the solicitor raised her slender eyebrows, gave me a bitter little smile. Well, then he knew exactly what he was doing, she said." Whether she imputes that view to the solicitor or not, Cusk still wants it both ways: we're asked to imagine her ex as such a magnificent lawyer that he managed to make her feel as though she were conscripting him, when all along, they were working to his long-game. Her feelings of maternal alienation were, in this version, a confection of his, with the aim of divorcing her some years down the line and pinching half her salary. Not since we met Heathcliff have readers been presented with an anti-hero whose grudges are so intricately prosecuted.

But she's like a lion, depositing a trophy kill: you might feel a bit queasy about it from some angles, but there is so much meat here. "Help is dangerous because it exists outside the human economy: the only payment for help is gratitude," she writes, distilling that awkwardness between couples, especially between parents, the tightrope between being put-upon and beholden. There is something marvellous, even monumental, about her honesty, the unabashed importance she attaches to every event: "I went to Paris for two days with my husband, determined while I was there to have my hair cut in a French salon. Wasn't this what women did? Well, I wanted to be womanised; I wanted someone to restore to me my lost femininity. A male hairdresser cut off all my hair, giggling as he did it, amusing himself during a boring afternoon at the salon by giving a tired blank-faced mother of two something punky and nouvelle vague. Afterwards, I wandered in the Paris streets, anxiously catching my reflection in shop windows. Had a transformation occurred, or a defacement? I wasn't sure. My husband wasn't sure either. It seemed terrible that between us we couldn't establish the truth." There is a topnote of derision for her own sex ("wasn't this what women did?") that is a much more likely wellspring than Cusk's divorce for her suspicions over whether or not she is still a feminist. But sisterliness and feminism have never been interchangeable; they are less so now than ever, as the expansion of our choices has shaped us into so many varieties.

Her final paragraph is evocative to an almost supernatural degree: "I begin to notice, looking in through those imaginary brightly lit windows, that the people inside are looking out. I see the women, these wives and mothers, looking out. They seem happy enough, contented enough, capable enough: they are well dressed, attractive, standing around with their men and their children. Yet they look around, their mouths moving. It is as though they are missing something or wondering about something. I remember it so well, what it was to be one of them. Sometimes one of these glances will pass over me and our eyes will briefly meet. And I realise she can't see me, this woman whose eyes have locked with mine. It isn't that she doesn't want to, or is trying not to. It's just that inside it's so bright and outside it's so dark, and so she can't see out, can't see anything at all."

Cusk gazes at herself unblinkingly, and judges harshly what she sees. But to call herself not a feminist? Hahaha. Of course she's one.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: How to be a woman

Re: How to be a woman

Erica Jong: Sex and motherhood

Feminist author Erica Jong and her daughter Molly have very different ideas about parenting and sex – one famously bohemian, the other conservative. Kira Cochrane meets them

Kira Cochrane The Guardian, Saturday 16 July 2011

'Mum thinks I'm a prude' ... Erica Jong and her daughter, Molly Jong-Fast, at Erica's apartment in New York. Photograph: Tim Knox for the Guardian

In Erica Jong's vast apartment, the Manhattan skyline thrusting up to my right, an image of a naked woman sprawling across a wall to my left, we are talking about sex. Specifically, nudity. Erica's daughter, Molly Jong-Fast, is with us and I'm trying to find out what it was like for her to grow up with a writer synonymous with the sexual revolution – that era of feminism, threesomes, consciousness-raising and beautiful, bountiful pubic bushes.

Molly has made some outlandish claims about her mother in the past, and it can be hard to work out what is true, what is satire. Did Erica really saunter around the house completely naked? "She was totally naked all the time," says Molly firmly, "and my grandmother too". She prods her mother for confirmation. "Were you naked all the time?"

"Carmen is just going to prepare a little bit of cheese," says Erica airily, ignoring the question, motioning to a woman working in the kitchen.

"There was a lot of disgusting nakedness," Molly repeats.

"You sleep in the nude," she says accusingly to her mother.

"But lots of people sleep in the nude," I say. "It gets hot."

Her mother goes to fetch fruit.

"Not in America," says Molly. "We have air conditioning. I sleep in six sweaters".

"It's not like I took you to nudist camps for vacation," says Erica, returning with a bowl of ripe figs, "They're good," she says, biting into one. She proffers them graciously.

Some people were concerned about how Molly would cope with being raised by Erica – the woman who published Fear of Flying in 1973, coined the phrase "zipless fuck" to describe a perfectly liberating encounter and became world famous when the novel sold more than 18m copies. When Molly was a child, therapists plagued her with the question: "Are you repressed by your mother's erotic writing?"

Frankly, the idea of Molly being repressed by anything seems absurd. Loud, arch and snappishly funny, she has the mien of a runaway train, words hurtling forth, helter-skelter.

"The men my mother dated were unbelievable. Un-be-lieve-able," says Molly.

"Scumbags!" says Erica, laughing uproariously.

"I mean, this is the problem with my mother," Molly continues. "She is not a good judge of character. She's a wonderful person. She's very trusting – the kind of person who gives her stalker her cell phone number." (Probably not any more. A few years ago, Erica wrote that she had stopped answering fan mail after one man requested her used underwear and another invited her to become "Mistress of Measurements" for his club, The Hung Jury.)

"I don't know how she found Ken," says Molly, referring to her mother's fourth husband, with whom she's been for 22 years, "because each boyfriend was worse than the next."

She starts running through a list of possibly libellous, possibly entirely true stories about the men in question – a glittering roster of fat jailbirds and motorcycling drug dealers.

"She had one boyfriend I loved and I was so disappointed she didn't marry him. But I think he was homosexual. There was another I liked, too, but he was married to someone else. Also, he wasn't successful. The only guy she ever went out with where I was like, 'Damn, he got away,'" she gives a loud, regretful finger snap, "was [financier] Steve Schwarzman."

"A Republican," says Erica.

"But we would be so rich," says Molly. "I'm just saying. It's a little disturbing."

In her memoir Girl [Maladjusted], published in 2006, Molly wrote about her "semi-celebrity childhood" with Erica, who divorced Jonathan Fast, her third husband, when their daughter was four. After that, Erica spent most of the 1980s dating, and this made it possible, wrote Molly, "for me to get married at a very young age and still know what's out there". The main lesson she learned during this period was never to date a man who "has more than one personality or is currently receiving electroshock treatment".

She returns to this subject in the essay "They had sex so I didn't have to", a highlight of the new anthology, Sugar in my Bowl. The book was edited by Erica, who wasn't sure she wanted to preside over a collection of sex essays by women – more typecasting, she thought – until the stories began rolling in, in all their juicy variety.

Editing the collection, Erica noticed a strong generational difference. "The older women were much raunchier," she says. Molly, who never passes up an opportunity to be outrageous, suggests that this is because the only people who like writing about sex are "the ones you would never want to have sex with in a million years, the 70-year-olds".

Her 69-year-old mother balks mildly. "Fay Weldon?" says Erica. "You wouldn't want to have sex with Fay?"

"Well, I love Fay," Molly concedes. "But not in that way."

Molly maps out the gulf between young and old in more detail in her essay, writing that while her mother grew up in a culture where sex was secretive and tightly tied to marriage, she grew up in a sex-obsessed era, with Britney Spears, for instance, constantly on-screen, "pulsating in a bikini, musing on her virginity". They each reacted against their circumstances, and against the mores of the previous generation – as did many of their peers. As Erica writes in her 1994 memoir, Fear of Fifty, "rebelling generations follow quiescent ones, quiescent ones follow rebelling ones and the world goes on as it always has".

So Erica became a sexual rebel among rebels, rolling through relationships with men and women, writing ecstatic, funny books that celebrated sexual pleasure and opportunity and imagination, literary, significant novels, whose pages nonetheless fall open at the dirty parts when you pick them up in charity shops.

Their life was full of privilege, affluence and anxiety. As a single parent, Erica supported two households, in the country and the city, and had to be very driven, she says. "I kept thinking I would never get another book contract and I would be broke, and it was really scary."

A nanny helped to look after Molly, and she was determined to give her daughter space to develop. Now, she fears, women are being shunted back to the home. She recently wrote in the Wall Street Journal about the rise of helicopter parenting, "the smothering surveillance of a child's every experience and problem", an approach, she believes, that imprisons women.

In response to Erica's motherhood essay, Molly wrote that she spends "a ton of time with my children, never travel, barely work and am a helicopter parent like you can't believe". Now 32, she married at 25, and had three children – Max, seven, and three-year-old twins, Darwin and Beatrice. Her husband used to be an academic but, says Molly: "I helped him out of that. I was like, being a college professor is so stupid." He now works in finance. In 2007, it was reported that the family had moved into a $5m apartment.

Molly writes in the anthology: "In the eyes of Erica Jong, I am a prude … a low-rent yuppie, shuttling my children back and forth to the various and sundry activities and involving myself in the Parents' Association. I am the person my grandmother and mother would have watched in silent scorn. I sometimes tell my children that my most important job is taking care of them."

I can't quite imagine Erica looking scornfully at her daughter. Throughout the interview, as Molly speaks, coming across like a contrarian in her cups (while drinking nothing harder than water), Erica gazes at her through pretty, saucerish eyes. She looks astonished at what she has created. Astonished and proud. There is none of the envy or resentment that can characterise mother and daughter relationships; they praise each other's writing, say they couldn't do what the other has done and finish each other's jokes. "You are funny, Molly," says Erica drily, as her daughter whips forth another wisecrack. "You really are."

Erica once wrote, "Women identify with their mothers automatically and powerfully, but they must also overthrow their mothers to become themselves." In Molly's case, the task of establishing her own identity and voice must have been especially tough. There were difficult years. As a teenager she was bulimic – partly a reaction, she has written, to Joan Collins telling her she was too fat to go on the yacht belonging to Valentino, the fashion designer. And she checked herself into rehab, aged 19, to address an addiction to booze and drugs. She has been sober ever since. But she seems to have established herself now and with aplomb.

She has just published her second novel, The Social Climber's Handbook – the story of a woman who becomes a serial killer to aid her husband's career. Molly says it's about seizing power in a world that doesn't value you. "I know a lot of people, a lot of wives, who don't work now. The problem is that so much self-esteem, especially in New York, is tied up with your importance. You just don't have much if your children are the only people who think you're important."

"So you're saying women can only get power by murdering people?" says Erica

"Yes. That's the only way."

"Murder is the new feminism!" the two women say at once, laughing.

Molly glories in the differences between herself and her mother. Where Erica is bohemian, Molly is bourgeois, where Erica is liberal, her daughter has an edge of conservatism. It's difficult to tell how many of Molly's stories are strictly accurate or wildly satirical. I decide to test a few more of them. Is it true that when she was growing up the house was full of pictures of "naked lesbians fooling around"?

"The naked lesbian painting? Yes indeed."

"It was a gift," says Erica, pouting slightly.

"But it doesn't matter if it was a gift. It existed ... There was a lot of naked art. Even in this house there's a lot of naked art." Molly turns gleefully to her mother. "I'm taking her into the bedroom so she can see the erotic carvings. I will do that. Because there is a lot of really dirty art in this house. What about the guy with the pipe? Where's the picture with the pipe?"

"It was sold."

"Oh, that breaks my heart. A man sodomising another man with a pipe has been sold."

Erica has had open relationships in the past and Molly writes that both sets of grandparents had open marriages too. I ask Erica if this is true of her parents. Molly jumps in, "Well, he cheated on her."

"I don't know if that's considered an open marriage!" says Erica.

"It's open on one side," says Molly. Erica says she doesn't have an open marriage any more because they don't work. "People get jealous. There are very few who are capable of it. I know one or two of the old bohemians, now dead, who were able to do that and weren't possessive, but jealousy is very hard to eradicate."

She says she didn't dare give Molly sex advice when she was growing up: "She would have laughed me out of the room." Molly certainly cracks up at the thought of some sex advice her mother gave one man they know, "who had a nice marriage and always felt close to Mum, and came to her for relationship advice". Her eyes widen, teeth glint. "Dun, dun, DARRRRR!" she says. "He told Mum, 'I'm going to have a ménage à trois with this young woman – what do you think?' And Mum said, 'Do it, it's great!'" She holds up a thumb sarcastically.

"I did not!" says Erica.

"And dun, de-dun, dun-DAR – he left! They got divorced and now he's with a young woman. Wa-wa-wa-WAAAAH."

The only time Erica risked giving sex advice to her daughter was when she was asked for some by one of Molly's childhood friends. The two girls were about 11. "She said, 'How should we decide who to lose our virginity to?'" says Erica, "and I replied, 'Make sure he's really nice and won't talk about you to other people.'"

Molly goes off to phone her therapist and Erica says she feels she was much more "suppressed by my mother than Molly was by me". Erica's mother wanted to be a painter but faced serious obstacles. At art school, for instance, she was told she had missed out on the top prize of a travelling fellowship because she was expected to marry, have children and give up art – and this filled her with rage. This frightened Erica away from painting, which she loved, too. "I was very overwhelmed by her because she was a very strong character. Much more overwhelmed than Molly was."

The two women seem impeccably close – the day after our interview they are off to the Hamptons together, on holiday. "I'm very proud of her," says Erica. "She's taken on things I never did. I had one child, she has three. She's brave. And she must feel very loved, even though she says she has low self-esteem, because otherwise how could she satirise me? She knows I'll never take umbrage. I give her permission to be whatever she wants to be."

And wasn't that the promise of the sexual and feminist revolutions? That women (and men) would be liberated to define themselves as they wished. As a prude, helicopter parent and biting social satirist, Molly Jong-Fast is honouring her mother's values in the most unexpected way.

Sugar in My Bowl, edited by Erica Jong, is published by Harper Collins, £12.99.

Feminist author Erica Jong and her daughter Molly have very different ideas about parenting and sex – one famously bohemian, the other conservative. Kira Cochrane meets them

Kira Cochrane The Guardian, Saturday 16 July 2011

'Mum thinks I'm a prude' ... Erica Jong and her daughter, Molly Jong-Fast, at Erica's apartment in New York. Photograph: Tim Knox for the Guardian

In Erica Jong's vast apartment, the Manhattan skyline thrusting up to my right, an image of a naked woman sprawling across a wall to my left, we are talking about sex. Specifically, nudity. Erica's daughter, Molly Jong-Fast, is with us and I'm trying to find out what it was like for her to grow up with a writer synonymous with the sexual revolution – that era of feminism, threesomes, consciousness-raising and beautiful, bountiful pubic bushes.

Molly has made some outlandish claims about her mother in the past, and it can be hard to work out what is true, what is satire. Did Erica really saunter around the house completely naked? "She was totally naked all the time," says Molly firmly, "and my grandmother too". She prods her mother for confirmation. "Were you naked all the time?"

"Carmen is just going to prepare a little bit of cheese," says Erica airily, ignoring the question, motioning to a woman working in the kitchen.

"There was a lot of disgusting nakedness," Molly repeats.

"You sleep in the nude," she says accusingly to her mother.

"But lots of people sleep in the nude," I say. "It gets hot."

Her mother goes to fetch fruit.

"Not in America," says Molly. "We have air conditioning. I sleep in six sweaters".

"It's not like I took you to nudist camps for vacation," says Erica, returning with a bowl of ripe figs, "They're good," she says, biting into one. She proffers them graciously.

Some people were concerned about how Molly would cope with being raised by Erica – the woman who published Fear of Flying in 1973, coined the phrase "zipless fuck" to describe a perfectly liberating encounter and became world famous when the novel sold more than 18m copies. When Molly was a child, therapists plagued her with the question: "Are you repressed by your mother's erotic writing?"

Frankly, the idea of Molly being repressed by anything seems absurd. Loud, arch and snappishly funny, she has the mien of a runaway train, words hurtling forth, helter-skelter.

"The men my mother dated were unbelievable. Un-be-lieve-able," says Molly.

"Scumbags!" says Erica, laughing uproariously.

"I mean, this is the problem with my mother," Molly continues. "She is not a good judge of character. She's a wonderful person. She's very trusting – the kind of person who gives her stalker her cell phone number." (Probably not any more. A few years ago, Erica wrote that she had stopped answering fan mail after one man requested her used underwear and another invited her to become "Mistress of Measurements" for his club, The Hung Jury.)

"I don't know how she found Ken," says Molly, referring to her mother's fourth husband, with whom she's been for 22 years, "because each boyfriend was worse than the next."

She starts running through a list of possibly libellous, possibly entirely true stories about the men in question – a glittering roster of fat jailbirds and motorcycling drug dealers.

"She had one boyfriend I loved and I was so disappointed she didn't marry him. But I think he was homosexual. There was another I liked, too, but he was married to someone else. Also, he wasn't successful. The only guy she ever went out with where I was like, 'Damn, he got away,'" she gives a loud, regretful finger snap, "was [financier] Steve Schwarzman."

"A Republican," says Erica.

"But we would be so rich," says Molly. "I'm just saying. It's a little disturbing."

In her memoir Girl [Maladjusted], published in 2006, Molly wrote about her "semi-celebrity childhood" with Erica, who divorced Jonathan Fast, her third husband, when their daughter was four. After that, Erica spent most of the 1980s dating, and this made it possible, wrote Molly, "for me to get married at a very young age and still know what's out there". The main lesson she learned during this period was never to date a man who "has more than one personality or is currently receiving electroshock treatment".

She returns to this subject in the essay "They had sex so I didn't have to", a highlight of the new anthology, Sugar in my Bowl. The book was edited by Erica, who wasn't sure she wanted to preside over a collection of sex essays by women – more typecasting, she thought – until the stories began rolling in, in all their juicy variety.

Editing the collection, Erica noticed a strong generational difference. "The older women were much raunchier," she says. Molly, who never passes up an opportunity to be outrageous, suggests that this is because the only people who like writing about sex are "the ones you would never want to have sex with in a million years, the 70-year-olds".

Her 69-year-old mother balks mildly. "Fay Weldon?" says Erica. "You wouldn't want to have sex with Fay?"

"Well, I love Fay," Molly concedes. "But not in that way."

Molly maps out the gulf between young and old in more detail in her essay, writing that while her mother grew up in a culture where sex was secretive and tightly tied to marriage, she grew up in a sex-obsessed era, with Britney Spears, for instance, constantly on-screen, "pulsating in a bikini, musing on her virginity". They each reacted against their circumstances, and against the mores of the previous generation – as did many of their peers. As Erica writes in her 1994 memoir, Fear of Fifty, "rebelling generations follow quiescent ones, quiescent ones follow rebelling ones and the world goes on as it always has".

So Erica became a sexual rebel among rebels, rolling through relationships with men and women, writing ecstatic, funny books that celebrated sexual pleasure and opportunity and imagination, literary, significant novels, whose pages nonetheless fall open at the dirty parts when you pick them up in charity shops.

Their life was full of privilege, affluence and anxiety. As a single parent, Erica supported two households, in the country and the city, and had to be very driven, she says. "I kept thinking I would never get another book contract and I would be broke, and it was really scary."

A nanny helped to look after Molly, and she was determined to give her daughter space to develop. Now, she fears, women are being shunted back to the home. She recently wrote in the Wall Street Journal about the rise of helicopter parenting, "the smothering surveillance of a child's every experience and problem", an approach, she believes, that imprisons women.

In response to Erica's motherhood essay, Molly wrote that she spends "a ton of time with my children, never travel, barely work and am a helicopter parent like you can't believe". Now 32, she married at 25, and had three children – Max, seven, and three-year-old twins, Darwin and Beatrice. Her husband used to be an academic but, says Molly: "I helped him out of that. I was like, being a college professor is so stupid." He now works in finance. In 2007, it was reported that the family had moved into a $5m apartment.

Molly writes in the anthology: "In the eyes of Erica Jong, I am a prude … a low-rent yuppie, shuttling my children back and forth to the various and sundry activities and involving myself in the Parents' Association. I am the person my grandmother and mother would have watched in silent scorn. I sometimes tell my children that my most important job is taking care of them."

I can't quite imagine Erica looking scornfully at her daughter. Throughout the interview, as Molly speaks, coming across like a contrarian in her cups (while drinking nothing harder than water), Erica gazes at her through pretty, saucerish eyes. She looks astonished at what she has created. Astonished and proud. There is none of the envy or resentment that can characterise mother and daughter relationships; they praise each other's writing, say they couldn't do what the other has done and finish each other's jokes. "You are funny, Molly," says Erica drily, as her daughter whips forth another wisecrack. "You really are."

Erica once wrote, "Women identify with their mothers automatically and powerfully, but they must also overthrow their mothers to become themselves." In Molly's case, the task of establishing her own identity and voice must have been especially tough. There were difficult years. As a teenager she was bulimic – partly a reaction, she has written, to Joan Collins telling her she was too fat to go on the yacht belonging to Valentino, the fashion designer. And she checked herself into rehab, aged 19, to address an addiction to booze and drugs. She has been sober ever since. But she seems to have established herself now and with aplomb.

She has just published her second novel, The Social Climber's Handbook – the story of a woman who becomes a serial killer to aid her husband's career. Molly says it's about seizing power in a world that doesn't value you. "I know a lot of people, a lot of wives, who don't work now. The problem is that so much self-esteem, especially in New York, is tied up with your importance. You just don't have much if your children are the only people who think you're important."

"So you're saying women can only get power by murdering people?" says Erica

"Yes. That's the only way."

"Murder is the new feminism!" the two women say at once, laughing.

Molly glories in the differences between herself and her mother. Where Erica is bohemian, Molly is bourgeois, where Erica is liberal, her daughter has an edge of conservatism. It's difficult to tell how many of Molly's stories are strictly accurate or wildly satirical. I decide to test a few more of them. Is it true that when she was growing up the house was full of pictures of "naked lesbians fooling around"?

"The naked lesbian painting? Yes indeed."

"It was a gift," says Erica, pouting slightly.

"But it doesn't matter if it was a gift. It existed ... There was a lot of naked art. Even in this house there's a lot of naked art." Molly turns gleefully to her mother. "I'm taking her into the bedroom so she can see the erotic carvings. I will do that. Because there is a lot of really dirty art in this house. What about the guy with the pipe? Where's the picture with the pipe?"

"It was sold."

"Oh, that breaks my heart. A man sodomising another man with a pipe has been sold."

Erica has had open relationships in the past and Molly writes that both sets of grandparents had open marriages too. I ask Erica if this is true of her parents. Molly jumps in, "Well, he cheated on her."