After the Royal Wedding euphoria, a timely reminder of how the other half lives

Page 1 of 1

After the Royal Wedding euphoria, a timely reminder of how the other half lives

After the Royal Wedding euphoria, a timely reminder of how the other half lives

So You Think You Know About Britain? by Danny Dorling - review

An angry study of Britain's ever-increasing inequalities

Lynsey Hanley The Guardian, Saturday 23 April 2011

Easterhouse in Glasgow. Photograph: Murdo Macleod

Danny Dorling is a professor of geography who has dedicated his career to exposing the deep social costs of inequality. This book is his first for a general readership, coming a year after Injustice, a detailed distillation of 20 years' research into the effects of neo-liberal economic policy on Britain's social fabric.

So You Think You Know About Britain? by Danny Dorling

What is most valuable about his writing is that it is angry, rather than indignant. You are asked not to wring your hands but to examine the relationship between your place in society and the place in which you live, and in so doing to recognise that there are winners and losers, rather than the deserving and undeserving.

The richer the area you live in, the easier your path through life will be; the poorer it is, the harder it will be. No longer can a majority of areas in Britain be described as "average" – that is, with a broad mix of people doing different jobs and earning a range of incomes. Areas are diverging in character, both socially and economically. Divorcees, for instance, tend to move to the coast, for cheaper housing.

The only significant way in which we are becoming less ghettoised is by race: black and Asian people are now less likely to be concentrated in cities or in poor areas of towns than they once were. Otherwise, we are more trammelled by postcode than ever, which leads to "nicer" areas becoming even more desirable, and therefore more attractive to people who can shell out to get away from undesirable people and areas.

In Dorling's view, our understandable desire to make our lives easier, wherever possible, leads us collectively to place greater pressure on parts of our social and geographical infrastructure than is necessary. "We now only have a shortage of housing in Britain," he writes, "because we share out our stock so badly – we have never had as many bedrooms per person as we have now."

The shortage of suitable housing for all the people who need it causes prices to rise in the private sector, which in turn leads to waiting lists increasing in the public sector. Successive governments have restricted the building of new social housing for essentially political reasons, forcing many people into owner-occupation when they can't really afford it.

A lack of suitable housing near to suitable jobs, at a time when government policy has undermined public transport and promoted the car, has caused us to clog up the roads by commuting to jobs that will pay our higher mortgages. What we need to start doing, Dorling argues, is to "point out repeatedly how precarious we have made our lives" and to ask "if there were not a better way we could arrange our affairs".

That would require all of us to start demanding more of our governments than to tell us things they think we want to hear while doing things we didn't vote for. For us all to be equally equipped to do so would require each of us to have a voice that will be heard, whether we're piping up from above the fourth floor of a tower block (one instance where you are more likely to be ghettoised by race) or from rich rural Oxfordshire.

For our towns, cities and villages to become as socially mixed as they were back in the mid-1970s, from when all markers of inequality in Britain began to rise, nearly 2.5 million of us would have to move – poorer people to richer areas, and richer people to poorer ones. This shows how many people have won or lost, more dramatically than was possible before 1979, under the new rules of the "property-owning democracy".

Dorling believes that knowledge is power: that if we have the facts, then we will act on our unease and seek to live lives that are a little less pressured and fearful. "For this country to change for the better," he concludes, "we must all get to know it better." If you need to be persuaded of such a case, there is no better book to read.

Lynsey Hanley's Estates: An Intimate History is published by Granta Books.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

An angry study of Britain's ever-increasing inequalities

Lynsey Hanley The Guardian, Saturday 23 April 2011

Easterhouse in Glasgow. Photograph: Murdo Macleod

Danny Dorling is a professor of geography who has dedicated his career to exposing the deep social costs of inequality. This book is his first for a general readership, coming a year after Injustice, a detailed distillation of 20 years' research into the effects of neo-liberal economic policy on Britain's social fabric.

So You Think You Know About Britain? by Danny Dorling

What is most valuable about his writing is that it is angry, rather than indignant. You are asked not to wring your hands but to examine the relationship between your place in society and the place in which you live, and in so doing to recognise that there are winners and losers, rather than the deserving and undeserving.

The richer the area you live in, the easier your path through life will be; the poorer it is, the harder it will be. No longer can a majority of areas in Britain be described as "average" – that is, with a broad mix of people doing different jobs and earning a range of incomes. Areas are diverging in character, both socially and economically. Divorcees, for instance, tend to move to the coast, for cheaper housing.

The only significant way in which we are becoming less ghettoised is by race: black and Asian people are now less likely to be concentrated in cities or in poor areas of towns than they once were. Otherwise, we are more trammelled by postcode than ever, which leads to "nicer" areas becoming even more desirable, and therefore more attractive to people who can shell out to get away from undesirable people and areas.

In Dorling's view, our understandable desire to make our lives easier, wherever possible, leads us collectively to place greater pressure on parts of our social and geographical infrastructure than is necessary. "We now only have a shortage of housing in Britain," he writes, "because we share out our stock so badly – we have never had as many bedrooms per person as we have now."

The shortage of suitable housing for all the people who need it causes prices to rise in the private sector, which in turn leads to waiting lists increasing in the public sector. Successive governments have restricted the building of new social housing for essentially political reasons, forcing many people into owner-occupation when they can't really afford it.

A lack of suitable housing near to suitable jobs, at a time when government policy has undermined public transport and promoted the car, has caused us to clog up the roads by commuting to jobs that will pay our higher mortgages. What we need to start doing, Dorling argues, is to "point out repeatedly how precarious we have made our lives" and to ask "if there were not a better way we could arrange our affairs".

That would require all of us to start demanding more of our governments than to tell us things they think we want to hear while doing things we didn't vote for. For us all to be equally equipped to do so would require each of us to have a voice that will be heard, whether we're piping up from above the fourth floor of a tower block (one instance where you are more likely to be ghettoised by race) or from rich rural Oxfordshire.

For our towns, cities and villages to become as socially mixed as they were back in the mid-1970s, from when all markers of inequality in Britain began to rise, nearly 2.5 million of us would have to move – poorer people to richer areas, and richer people to poorer ones. This shows how many people have won or lost, more dramatically than was possible before 1979, under the new rules of the "property-owning democracy".

Dorling believes that knowledge is power: that if we have the facts, then we will act on our unease and seek to live lives that are a little less pressured and fearful. "For this country to change for the better," he concludes, "we must all get to know it better." If you need to be persuaded of such a case, there is no better book to read.

Lynsey Hanley's Estates: An Intimate History is published by Granta Books.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: After the Royal Wedding euphoria, a timely reminder of how the other half lives

Re: After the Royal Wedding euphoria, a timely reminder of how the other half lives

The Potato Eaters (1885). Van Gogh Museum.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: After the Royal Wedding euphoria, a timely reminder of how the other half lives

Re: After the Royal Wedding euphoria, a timely reminder of how the other half lives

Visions of England by Roy Strong - review

The pastoral has political uses

Terry Eagleton guardian.co.uk, Friday 1 July 2011 09.45 BST

Thomas Gainsborough's Mr and Mrs Andrews. Photograph: National Gallery, London

The vision of the English countryside as an Arcadian paradise of rosy-cheeked peasants was largely the creation of town dwellers. It is the myth of those for whom the country is a place to look at rather than live in. Thomas Hardy, one of the finest of all memorialists of rural England, knew that there were scarcely any peasants to be found there at all, if by "peasant" one means a farmer who owns and works his own land. Most of them had been reduced to landless labourers by market forces and the Enclosure Acts, or driven into the satanic mills of early industrial England. There was nothing timeless or idyllic about this landscape of capitalist landowners, grinding poverty, depopulation and a decaying artisanal class, which is one reason why Hardy is not the most cheerful of authors.

Visions of England by Sir Roy Strong

Roy Strong's vision of England, by contrast, is a dream of rural harmony. His book begins with a florid gush of praise for Elizabeth I, a woman one suspects he would dearly like to have moved in with, and takes us by way of Shakespeare, the Book of Common Prayer, Thomas Gainsborough and John Constable to Vaughan Williams, Edward Elgar, folk music and the National Trust. Not much for your average British Bangladeshi there. In an elegiac epilogue, the author laments the fact that so much history teaching today passes over this national heritage for such unpatriotic topics as the Russian revolution, the two world wars and the Holocaust. Our children are having their heads filled with Trotsky rather than the Tudors.

Strong may be a Romantic conservative, but he is not a fascist beast. In fact, the most astonishing aspect of his book is the way it stealthily undermines its own thesis. He is chary of history lessons that focus on Rommel rather than Rupert Brooke, but admits that his own education was excessively Anglocentric. He also welcomes multiculturalism, even if he would clearly like Pakistanis to learn all about manor houses and morris dancing. Nor is he far from confessing that the proud lineage of British Protestantism might more accurately be described as visceral anti-Catholicism. Despite an anodyne reference to the "heroic voyages" of such squalid adventurers as Drake and Raleigh, he is well aware of the role played by imperialism in the formation of British identity. He also notes that one of the keynotes of that identity was a sense of "external threat", a polite way of describing a pathological racist revulsion at all things French. Without the French to execrate, the British would have had no more idea of who they were than a spaniel.

Most astonishingly of all, Strong sails close to acknowledging that the subject at the heart of his book is all a con. It is an "invented paradise", which glosses over the social inequalities and "appalling depression" of rural England. The great 18th-century landscape painters may show the landowner gazing benignly on his flocks of sheep and abundant harvest, but Strong reminds us that there is no sign of those who actually till the soil. (He might have added that much the same is true of Jane Austen, who has a remarkably astute eye for the value and size of a landed estate, but never sees anyone working there.) Paintings that romanticised rural life, the book points out, were displayed on the walls of some of the very landowners who, by mechanising and enclosing the countryside, were helping to destroy the communities these images commemorated. The former director of the Victoria & Albert museum seems to teeter on the very brink of Marxist talk about social contradictions.

The pastoral, in short, is the invention of patricians. Nostalgia can serve the purposes of the hard-headed, as with today's heritage industry. Because rural landscapes do not change all that much, Box Hill being pretty much the same place today as when Austen wrote about it, it is easy to imagine that the way of life which goes on in their midst is eternal as well. Strong is alert to this mistake, as well as to just how much these dewy-eyed icons of England exclude. The industrial revolution is written out of the nation's self-image, and along with it more or less everything north of Warwickshire. Englishness is more a matter of the south Downs than the Yorkshire moors. Our sense of the nation is the imaginary construct of poets, Strong concedes, not a reflection of reality.

The idea of a timeless rural England emerged at exactly the point when the country was becoming the first in the world to undergo industrialisation. The countryside, in short, became changeless just when it started to shrink. A couple of centuries earlier, when Shakespeare's John of Gaunt delivered his famous eulogy to "this scepter'd isle"', he was, so Strong points out, lamenting the passing of an England which was in fact being defined for the first time at that historical moment. As the critic Raymond Williams was fond of insisting, the only sure thing about the organic society is that it has always gone.

What is truly stunning about the book is that none of this in the end is allowed to count against the delusion of England as Arcadia. It may leave out rather a lot, but that is the way with myths. The exclusion of "factories and furnaces, slums and human degradation" from the nation's sense of selfhood is no great problem, since all such images are works of the imagination. One wonders whether Strong has ever heard of Dickens and Joyce, those mighty mythologists of the city. Why should the imagination not draw its inspiration from diesel engines as much as from haylofts? For all its bogusness, much of it well examined here, this preposterous vision of English society must be allowed to stand. It speaks, Strong informs us, of a "peaceful and tranquil" society, "that exists in harmony and where life follows the cycle of the seasons". Whenever one hears talk of social harmony, one can be sure that someone's interests are under threat. The fact that England is neither tranquil nor harmonious, and never has been, is no objection at all to this fantasy. Ideologies are not to be loused up with the facts. The rural vision remains the key source of the nation's identity.

There is, perversely, something to be said for Strong's decision to persist in this neo-Georgian delusion. Ruling-class English ideology has always involved a curious mixture of the rural and the imperial – which is to say, the peaceful and the bellicose, or even, stereotypically speaking, the feminine and masculine. Strong plumps for the former partly because he dislikes the idea of a national identity bloated with imperial mythology. As a spiritual aristocrat, he has no truck with the complacent notions of progress and conquest of a Whiggish middle class.

What this overlooks is the fact that these two visions are really sides of the same coin. The common soldiers who fought in the two world wars, Strong argues, may have come from factories and offices, but they fought in the name of Chipping Campden and Lavenham rather than Manchester or Birmingham. This isn't actually true. The great majority of these men would never have heard of Lavenham and fought because they were forced to. Yet in a garbled way, the point captures a kind of truth. Visions of peace and harmony are the agreeable illusions of which war and imperialism are the nightmarish underside. The thought of gathering lilacs in the spring again may be just enough to sustain you through Flanders or Dunkirk. In this sense, all utopia has an element of truth. When Strong writes of the English love of gardens in this book, he sees that there may be some race memory at work here, by which the citizens of post-rural England may find a fragile link back to the agricultural past of their ancestors. Not all nostalgia is morbid. But neither are we defined by the past, as this book dubiously suggests.

Terry Eagleton's Why Marx Was Right is published by Yale University Press (see ATU Literature section).

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

The pastoral has political uses

Terry Eagleton guardian.co.uk, Friday 1 July 2011 09.45 BST

Thomas Gainsborough's Mr and Mrs Andrews. Photograph: National Gallery, London

The vision of the English countryside as an Arcadian paradise of rosy-cheeked peasants was largely the creation of town dwellers. It is the myth of those for whom the country is a place to look at rather than live in. Thomas Hardy, one of the finest of all memorialists of rural England, knew that there were scarcely any peasants to be found there at all, if by "peasant" one means a farmer who owns and works his own land. Most of them had been reduced to landless labourers by market forces and the Enclosure Acts, or driven into the satanic mills of early industrial England. There was nothing timeless or idyllic about this landscape of capitalist landowners, grinding poverty, depopulation and a decaying artisanal class, which is one reason why Hardy is not the most cheerful of authors.

Visions of England by Sir Roy Strong

Roy Strong's vision of England, by contrast, is a dream of rural harmony. His book begins with a florid gush of praise for Elizabeth I, a woman one suspects he would dearly like to have moved in with, and takes us by way of Shakespeare, the Book of Common Prayer, Thomas Gainsborough and John Constable to Vaughan Williams, Edward Elgar, folk music and the National Trust. Not much for your average British Bangladeshi there. In an elegiac epilogue, the author laments the fact that so much history teaching today passes over this national heritage for such unpatriotic topics as the Russian revolution, the two world wars and the Holocaust. Our children are having their heads filled with Trotsky rather than the Tudors.

Strong may be a Romantic conservative, but he is not a fascist beast. In fact, the most astonishing aspect of his book is the way it stealthily undermines its own thesis. He is chary of history lessons that focus on Rommel rather than Rupert Brooke, but admits that his own education was excessively Anglocentric. He also welcomes multiculturalism, even if he would clearly like Pakistanis to learn all about manor houses and morris dancing. Nor is he far from confessing that the proud lineage of British Protestantism might more accurately be described as visceral anti-Catholicism. Despite an anodyne reference to the "heroic voyages" of such squalid adventurers as Drake and Raleigh, he is well aware of the role played by imperialism in the formation of British identity. He also notes that one of the keynotes of that identity was a sense of "external threat", a polite way of describing a pathological racist revulsion at all things French. Without the French to execrate, the British would have had no more idea of who they were than a spaniel.

Most astonishingly of all, Strong sails close to acknowledging that the subject at the heart of his book is all a con. It is an "invented paradise", which glosses over the social inequalities and "appalling depression" of rural England. The great 18th-century landscape painters may show the landowner gazing benignly on his flocks of sheep and abundant harvest, but Strong reminds us that there is no sign of those who actually till the soil. (He might have added that much the same is true of Jane Austen, who has a remarkably astute eye for the value and size of a landed estate, but never sees anyone working there.) Paintings that romanticised rural life, the book points out, were displayed on the walls of some of the very landowners who, by mechanising and enclosing the countryside, were helping to destroy the communities these images commemorated. The former director of the Victoria & Albert museum seems to teeter on the very brink of Marxist talk about social contradictions.

The pastoral, in short, is the invention of patricians. Nostalgia can serve the purposes of the hard-headed, as with today's heritage industry. Because rural landscapes do not change all that much, Box Hill being pretty much the same place today as when Austen wrote about it, it is easy to imagine that the way of life which goes on in their midst is eternal as well. Strong is alert to this mistake, as well as to just how much these dewy-eyed icons of England exclude. The industrial revolution is written out of the nation's self-image, and along with it more or less everything north of Warwickshire. Englishness is more a matter of the south Downs than the Yorkshire moors. Our sense of the nation is the imaginary construct of poets, Strong concedes, not a reflection of reality.

The idea of a timeless rural England emerged at exactly the point when the country was becoming the first in the world to undergo industrialisation. The countryside, in short, became changeless just when it started to shrink. A couple of centuries earlier, when Shakespeare's John of Gaunt delivered his famous eulogy to "this scepter'd isle"', he was, so Strong points out, lamenting the passing of an England which was in fact being defined for the first time at that historical moment. As the critic Raymond Williams was fond of insisting, the only sure thing about the organic society is that it has always gone.

What is truly stunning about the book is that none of this in the end is allowed to count against the delusion of England as Arcadia. It may leave out rather a lot, but that is the way with myths. The exclusion of "factories and furnaces, slums and human degradation" from the nation's sense of selfhood is no great problem, since all such images are works of the imagination. One wonders whether Strong has ever heard of Dickens and Joyce, those mighty mythologists of the city. Why should the imagination not draw its inspiration from diesel engines as much as from haylofts? For all its bogusness, much of it well examined here, this preposterous vision of English society must be allowed to stand. It speaks, Strong informs us, of a "peaceful and tranquil" society, "that exists in harmony and where life follows the cycle of the seasons". Whenever one hears talk of social harmony, one can be sure that someone's interests are under threat. The fact that England is neither tranquil nor harmonious, and never has been, is no objection at all to this fantasy. Ideologies are not to be loused up with the facts. The rural vision remains the key source of the nation's identity.

There is, perversely, something to be said for Strong's decision to persist in this neo-Georgian delusion. Ruling-class English ideology has always involved a curious mixture of the rural and the imperial – which is to say, the peaceful and the bellicose, or even, stereotypically speaking, the feminine and masculine. Strong plumps for the former partly because he dislikes the idea of a national identity bloated with imperial mythology. As a spiritual aristocrat, he has no truck with the complacent notions of progress and conquest of a Whiggish middle class.

What this overlooks is the fact that these two visions are really sides of the same coin. The common soldiers who fought in the two world wars, Strong argues, may have come from factories and offices, but they fought in the name of Chipping Campden and Lavenham rather than Manchester or Birmingham. This isn't actually true. The great majority of these men would never have heard of Lavenham and fought because they were forced to. Yet in a garbled way, the point captures a kind of truth. Visions of peace and harmony are the agreeable illusions of which war and imperialism are the nightmarish underside. The thought of gathering lilacs in the spring again may be just enough to sustain you through Flanders or Dunkirk. In this sense, all utopia has an element of truth. When Strong writes of the English love of gardens in this book, he sees that there may be some race memory at work here, by which the citizens of post-rural England may find a fragile link back to the agricultural past of their ancestors. Not all nostalgia is morbid. But neither are we defined by the past, as this book dubiously suggests.

Terry Eagleton's Why Marx Was Right is published by Yale University Press (see ATU Literature section).

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: After the Royal Wedding euphoria, a timely reminder of how the other half lives

Re: After the Royal Wedding euphoria, a timely reminder of how the other half lives

Archbishop laments 'broken bonds and abused trust' in British society

Dr Rowan Williams to refer to the aftermath of summer riots and financial speculation in his Christmas Day sermon

Press Association

guardian.co.uk, Sunday 25 December 2011 10.00 GMT

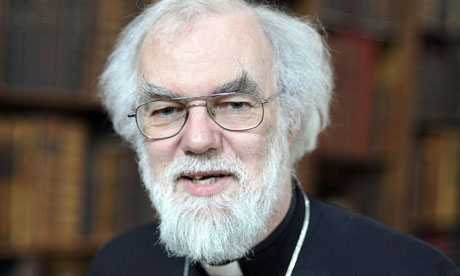

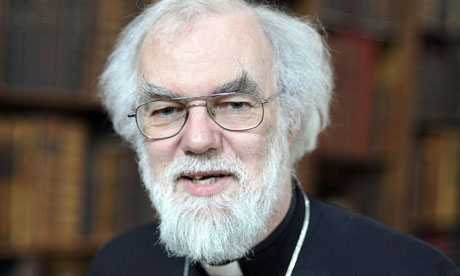

The archbishop of Canterbury has written before of his 'enormous sadness' during the summer riots. Photograph: Tim Ireland/PA

The archbishop of Canterbury is to speak of the "broken bonds and abused trust" in a British society torn apart by riots and financial speculation in his Christmas Day sermon.

Delivering his sermon from Canterbury Cathedral, Dr Rowan Williams will ask the congregation to learn lessons about "mutual obligation" from the events of the past year.

He will say: "The most pressing question we now face, we might well say, is who and where we are as a society. Bonds have been broken, trust abused and lost.

"Whether it is an urban rioter mindlessly burning down a small shop that serves his community, or a speculator turning his back on the question of who bears the ultimate cost for his acquisitive adventures in the virtual reality of today's financial world, the picture is of atoms spinning apart in the dark."

It is not the first time the archbishop has referred to last August's disturbances, which spread from Tottenham, north London, to cities across the country.

Writing in the Guardian this month, Williams spoke about the "enormous sadness" that he felt during the riots.

But he also said the government should do more to rescue young people "who think they have nothing to lose".

The Church of England has also been caught up in the struggle between anti-capitalist protesters camped in front of St Paul's Cathedral since October and the Corporation of London, which is fighting a legal battle to disband the campsite.

After initially giving support to the protesters, the canon chancellor of St Paul's, Dr Giles Fraser, resigned from his position on 27 October, following reports suggesting a rift between clergy over what action to take concerning the activists.

And Williams suggested in November he was sympathetic to a "Robin Hood" tax on share and currency transactions.

In his Christmas Day sermon, he will use the Book of Common Prayer – which will celebrate its 350th anniversary in 2012 – as an example of how ideas of duty and common interest can be expressed.

He quotes the Book of Common Prayer's Long Exhortation to say: "If ye shall perceive your offences to be such as are not only against God but also against your neighbours; then ye shall reconcile yourselves unto them; being ready to make restitution."

Dr Rowan Williams to refer to the aftermath of summer riots and financial speculation in his Christmas Day sermon

Press Association

guardian.co.uk, Sunday 25 December 2011 10.00 GMT

The archbishop of Canterbury has written before of his 'enormous sadness' during the summer riots. Photograph: Tim Ireland/PA

The archbishop of Canterbury is to speak of the "broken bonds and abused trust" in a British society torn apart by riots and financial speculation in his Christmas Day sermon.

Delivering his sermon from Canterbury Cathedral, Dr Rowan Williams will ask the congregation to learn lessons about "mutual obligation" from the events of the past year.

He will say: "The most pressing question we now face, we might well say, is who and where we are as a society. Bonds have been broken, trust abused and lost.

"Whether it is an urban rioter mindlessly burning down a small shop that serves his community, or a speculator turning his back on the question of who bears the ultimate cost for his acquisitive adventures in the virtual reality of today's financial world, the picture is of atoms spinning apart in the dark."

It is not the first time the archbishop has referred to last August's disturbances, which spread from Tottenham, north London, to cities across the country.

Writing in the Guardian this month, Williams spoke about the "enormous sadness" that he felt during the riots.

But he also said the government should do more to rescue young people "who think they have nothing to lose".

The Church of England has also been caught up in the struggle between anti-capitalist protesters camped in front of St Paul's Cathedral since October and the Corporation of London, which is fighting a legal battle to disband the campsite.

After initially giving support to the protesters, the canon chancellor of St Paul's, Dr Giles Fraser, resigned from his position on 27 October, following reports suggesting a rift between clergy over what action to take concerning the activists.

And Williams suggested in November he was sympathetic to a "Robin Hood" tax on share and currency transactions.

In his Christmas Day sermon, he will use the Book of Common Prayer – which will celebrate its 350th anniversary in 2012 – as an example of how ideas of duty and common interest can be expressed.

He quotes the Book of Common Prayer's Long Exhortation to say: "If ye shall perceive your offences to be such as are not only against God but also against your neighbours; then ye shall reconcile yourselves unto them; being ready to make restitution."

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: After the Royal Wedding euphoria, a timely reminder of how the other half lives

Re: After the Royal Wedding euphoria, a timely reminder of how the other half lives

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6-nzLCDK9Es&feature=related

One of Those Days in England- Roy Harper.

One of Those Days in England- Roy Harper.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Similar topics

Similar topics» The Royal Wedding

» Royal Wedding Video

» Bread and Circuses: The Royal Wedding

» What actors look like in the half-hour before they go on stage

» My wedding day.....

» Royal Wedding Video

» Bread and Circuses: The Royal Wedding

» What actors look like in the half-hour before they go on stage

» My wedding day.....

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum