Alan Bennett

Page 1 of 1

Alan Bennett

Alan Bennett

Smut: Two Unseemly Stories by Alan Bennett – review

Alan Bennett's witty, sly stories are a delight

Sarah Churchwell The Guardian, Saturday 23 April 2011

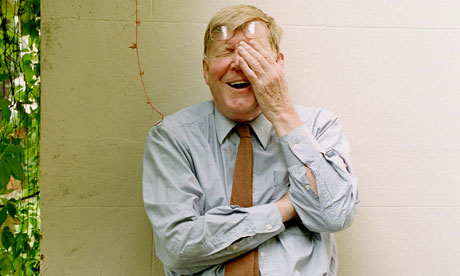

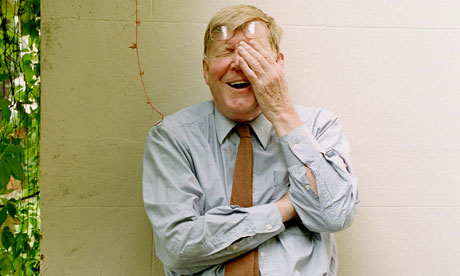

The comedy of misperception ... Smut offers plenty of Bennett's trademark pleasures. Photograph: Eamonn McCabe

Alan Bennett once remarked that his stage adaptation of The Wind in the Willows was partly about "keeping it under", in which Toad doesn't actually change his ways, but instead simply learns to "counterfeit" socially acceptable virtues in order to be accepted by his society. The phrase could serve as an equally apt description of Bennett's latest book, Smut: Two Unseemly Stories: both tales are about keeping it under, people counterfeiting ideal selves in order to be accepted.

Smut: Two Unseemly Stories by Alan Bennett

Indeed, the parallelism of "The Greening of Mrs Donaldson" and "The Shielding of Mrs Forbes" is signalled from the outset by the consonance of their titles. The first story tells of respectable, recently widowed Mrs Donaldson, who "was (or thought herself) a conventional middle-class woman beached on the shores of widowhood after a marriage that had been, she supposed, much like many others . . . happy to begin with, then satisfactory and finally dull." In order to supplement her pension, Mrs Donaldson takes in medical students from the nearby hospital, and is soon making a little money as a "part-time demonstrator" for the students, one of a handful of locals who pretend to have illnesses so that the student doctors can learn how to conduct examinations. She finds herself with an unexpected aptitude for acting, and an unexpected dilemma: the nice students boarding with her keep coming up short on the rent, and eventually offer to "work it off". Their offer turns out to be considerably less conventional than she expects, and soon Mrs Donaldson is entangled in a farcical sexual ménage that opens her eyes in more ways than one.

"The Shielding of Mrs Forbes" also concerns unconventional sexual arrangements among the apparently conventional. Another middle-class, middle-aged woman, snobbish, priggish Mrs Forbes has been blessed with an extremely handsome and quite stupid son, who has a secret: he is gay. With a mother determined to keep up appearances, however, Graham Forbes decides to marry a wealthy young woman who is much less attractive than he but much more intelligent. As Mrs Forbes bullies her gentle, frustrated husband, who consoles himself online with "a dusky beauty in Samoa (but who actually lives in Clitheroe)," Graham gets himself entangled with a blackmailing policeman, and his clever, determined wife takes control as once again, farce drives the story to its satirical denouement.

As these two brief quotations demonstrate, Bennett's humour in this small volume consistently resides in the logic of the parenthetical aside, the comedy of false appearances or misperceptions being challenged or disabused while the narrator barely pauses his gently barbed account. Mrs Donaldson is not as conventional as she thought herself, and no one around Mr Forbes is where – or who – they pretend to be.

Appropriately enough, given Bennett's day job, both stories are, in the end, about performing, about putting on a show for other people. Most of the characters think they're fooling the world, and most of them are quite incorrect. The book's theme is really less "smut" than it is the "unseemly," the pressures of decorum and social expectations. But it is also about the creative, even eccentric ways in which people use sex: the only couple in either tale who seems to enjoy a more or less conventional sexual relationship based on mutual affection and pleasure is also an adulterous quasi-incestuous liaison between a father and his daughter-in-law. Appearances are, of course, deceiving: Mrs Donaldson may not be as taken in as she seems, and Mrs Forbes needs less shielding than her family thinks.

But Bennett's satire is not really directed at the characters who counterfeit – if anything he treats them, characteristically, with some tenderness, as poor souls trapped in a plight that is at once funny and poignant. Instead, the satire is directed at performance itself, at a society of people desperately trying to take each other in and only managing to deceive themselves.

If Smut is undeniably slight – it's not clear that these two stories, however amusing, really warrant stand-alone publication – it also offers plenty of Bennett's trademark pleasures. It would be too much to say that he's challenging himself, but the book is by no means lazily written and it's consistently amusing, full of witty turns of phrase: "One does not have to be in the forefront of the struggle for women's rights to find Betty's decision to marry Graham deplorable. She wasn't wholly infatuated, though she liked the way he looked; but, so too did he and that unfatuated her a bit." I intend to use "unfatuated" in conversation as soon as possible. Given humanity, it shouldn't take long for an opportunity to present itself – a sentiment with which I am reasonably confident Alan Bennett would agree.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

Alan Bennett's witty, sly stories are a delight

Sarah Churchwell The Guardian, Saturday 23 April 2011

The comedy of misperception ... Smut offers plenty of Bennett's trademark pleasures. Photograph: Eamonn McCabe

Alan Bennett once remarked that his stage adaptation of The Wind in the Willows was partly about "keeping it under", in which Toad doesn't actually change his ways, but instead simply learns to "counterfeit" socially acceptable virtues in order to be accepted by his society. The phrase could serve as an equally apt description of Bennett's latest book, Smut: Two Unseemly Stories: both tales are about keeping it under, people counterfeiting ideal selves in order to be accepted.

Smut: Two Unseemly Stories by Alan Bennett

Indeed, the parallelism of "The Greening of Mrs Donaldson" and "The Shielding of Mrs Forbes" is signalled from the outset by the consonance of their titles. The first story tells of respectable, recently widowed Mrs Donaldson, who "was (or thought herself) a conventional middle-class woman beached on the shores of widowhood after a marriage that had been, she supposed, much like many others . . . happy to begin with, then satisfactory and finally dull." In order to supplement her pension, Mrs Donaldson takes in medical students from the nearby hospital, and is soon making a little money as a "part-time demonstrator" for the students, one of a handful of locals who pretend to have illnesses so that the student doctors can learn how to conduct examinations. She finds herself with an unexpected aptitude for acting, and an unexpected dilemma: the nice students boarding with her keep coming up short on the rent, and eventually offer to "work it off". Their offer turns out to be considerably less conventional than she expects, and soon Mrs Donaldson is entangled in a farcical sexual ménage that opens her eyes in more ways than one.

"The Shielding of Mrs Forbes" also concerns unconventional sexual arrangements among the apparently conventional. Another middle-class, middle-aged woman, snobbish, priggish Mrs Forbes has been blessed with an extremely handsome and quite stupid son, who has a secret: he is gay. With a mother determined to keep up appearances, however, Graham Forbes decides to marry a wealthy young woman who is much less attractive than he but much more intelligent. As Mrs Forbes bullies her gentle, frustrated husband, who consoles himself online with "a dusky beauty in Samoa (but who actually lives in Clitheroe)," Graham gets himself entangled with a blackmailing policeman, and his clever, determined wife takes control as once again, farce drives the story to its satirical denouement.

As these two brief quotations demonstrate, Bennett's humour in this small volume consistently resides in the logic of the parenthetical aside, the comedy of false appearances or misperceptions being challenged or disabused while the narrator barely pauses his gently barbed account. Mrs Donaldson is not as conventional as she thought herself, and no one around Mr Forbes is where – or who – they pretend to be.

Appropriately enough, given Bennett's day job, both stories are, in the end, about performing, about putting on a show for other people. Most of the characters think they're fooling the world, and most of them are quite incorrect. The book's theme is really less "smut" than it is the "unseemly," the pressures of decorum and social expectations. But it is also about the creative, even eccentric ways in which people use sex: the only couple in either tale who seems to enjoy a more or less conventional sexual relationship based on mutual affection and pleasure is also an adulterous quasi-incestuous liaison between a father and his daughter-in-law. Appearances are, of course, deceiving: Mrs Donaldson may not be as taken in as she seems, and Mrs Forbes needs less shielding than her family thinks.

But Bennett's satire is not really directed at the characters who counterfeit – if anything he treats them, characteristically, with some tenderness, as poor souls trapped in a plight that is at once funny and poignant. Instead, the satire is directed at performance itself, at a society of people desperately trying to take each other in and only managing to deceive themselves.

If Smut is undeniably slight – it's not clear that these two stories, however amusing, really warrant stand-alone publication – it also offers plenty of Bennett's trademark pleasures. It would be too much to say that he's challenging himself, but the book is by no means lazily written and it's consistently amusing, full of witty turns of phrase: "One does not have to be in the forefront of the struggle for women's rights to find Betty's decision to marry Graham deplorable. She wasn't wholly infatuated, though she liked the way he looked; but, so too did he and that unfatuated her a bit." I intend to use "unfatuated" in conversation as soon as possible. Given humanity, it shouldn't take long for an opportunity to present itself – a sentiment with which I am reasonably confident Alan Bennett would agree.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Alan Bennett

Re: Alan Bennett

Alan Bennett on audio - review

From Smut to knickers in Norwich

Sue Arnold The Guardian, Saturday 4 June 2011

Unlike the cartoon a reader has just sent me showing a man lying on a psychiatrist's couch asking incredulously "Are all the voices in my head Martin Jarvis's?", the only voice I'm offering this week is Alan Bennett's. As he has more than 100 audios to his credit, this hagiographic review of his BBC audios – inspired by his latest, Smut: Two Unseemly Stories (4hrs, £13.25) – is justified. The reviewer who said that, after Smut, Bennett's national treasure status should be revoked must lead a very sheltered life. Bennett was custom-built for audio, one of the very few people (Le Carré is another) who read their own books best. All the stories mentioned here, except those in the children's collection, were written and are read by him, ditto the diaries and memoirs.

Smut is vintage Bennett, especially the voice, so unremittingly lugubrious that, by comparison, his legendary Eeyore impersonation sounds blithe. In the first story, Mrs Donaldson, a widow in straitened circumstances, takes in student lodgers who suggest that in lieu of rent (they're three weeks behind) she might like to watch Andy and Laura give her "a demonstration". "Have you ever seen anyone making love?" said Laura. "Er – uhum, to tell you the truth," said Mrs Donaldson, pretending to cast her mind back, "I don't think I have." What follows on the Donaldsons' marital bed – robust, noisy, athletic – is not how Cyril used to do it.

Personally, I prefer Mrs Forbes in the second story, dismayed that her exceptionally good-looking son Graham is going to marry an exceptionally plain young woman called Betty Greene. "I wouldn't put it past her to be Jewish, I've known Green be a Jewish name," she tells her long-suffering husband. He points out that it's Greene with a silent e, like the Catholic novelist. "For Graham's mother – often taken for a widow, she had so much the air of a woman who is coping magnificently that a husband still extant took people by surprise – there was little to choose between Jews and Catholics. The Jews had holidays that turned up out of the blue and the Catholics had children in much the same way." Graham's gay lover complicates things, as does Betty's affair with her father-in-law, but Smut is really no saucier than everything Bennett writes. Remember the flurried housemaster in Forty Years On complaining "I wish I could put my hands on the choir's parts".

No need to rack your brains. It's in the boxed Three Plays edition (£30.60), with Bennett as headmaster every bit as good as Gielgud on stage, along with An Englishman Abroad and Kafka's Dick. The Englishman is Guy Burgess exiled in Moscow. It's the true story told to Bennett by Coral Browne, who met Burgess when the Old Vic took Hamlet to the USSR in 1958. He asked her to bring a tape measure to his drab, utilitarian flat and order him some new suits from his London tailor. Michael Gambon and Penelope Wilton both won Baftas for their performances in this radio adaptation. And Jim Broadbent should have got one for the World Service production of The Madness of George III (£13.25), on which Colin Firth must have based his King's Speech triumph.

My all-time favourite Bennett story is The Uncommon Reader (£13.25), about the Queen discovering the joy of reading, everywhere – at meals, corgi-walking, even in the state coach: "She'd got quite good at reading and waving, the trick being to keep the book below the level of the window and to keep focused on it and not on the crowds." Only Bennett, in Children's Classics (£35 boxed set), could keep Pooh, Alice and Toad on the right side of whimsy. His Diaries (£20.40) are frank and very funny, and all serious Bennett buffs will want the only surviving episode (thanks to Auntie's tape-recycling policy) of his 1966 TV series On the Margin (£9.25), which includes the famous "NORWICH" knickers telegram. Good listening.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

From Smut to knickers in Norwich

Sue Arnold The Guardian, Saturday 4 June 2011

Unlike the cartoon a reader has just sent me showing a man lying on a psychiatrist's couch asking incredulously "Are all the voices in my head Martin Jarvis's?", the only voice I'm offering this week is Alan Bennett's. As he has more than 100 audios to his credit, this hagiographic review of his BBC audios – inspired by his latest, Smut: Two Unseemly Stories (4hrs, £13.25) – is justified. The reviewer who said that, after Smut, Bennett's national treasure status should be revoked must lead a very sheltered life. Bennett was custom-built for audio, one of the very few people (Le Carré is another) who read their own books best. All the stories mentioned here, except those in the children's collection, were written and are read by him, ditto the diaries and memoirs.

Smut is vintage Bennett, especially the voice, so unremittingly lugubrious that, by comparison, his legendary Eeyore impersonation sounds blithe. In the first story, Mrs Donaldson, a widow in straitened circumstances, takes in student lodgers who suggest that in lieu of rent (they're three weeks behind) she might like to watch Andy and Laura give her "a demonstration". "Have you ever seen anyone making love?" said Laura. "Er – uhum, to tell you the truth," said Mrs Donaldson, pretending to cast her mind back, "I don't think I have." What follows on the Donaldsons' marital bed – robust, noisy, athletic – is not how Cyril used to do it.

Personally, I prefer Mrs Forbes in the second story, dismayed that her exceptionally good-looking son Graham is going to marry an exceptionally plain young woman called Betty Greene. "I wouldn't put it past her to be Jewish, I've known Green be a Jewish name," she tells her long-suffering husband. He points out that it's Greene with a silent e, like the Catholic novelist. "For Graham's mother – often taken for a widow, she had so much the air of a woman who is coping magnificently that a husband still extant took people by surprise – there was little to choose between Jews and Catholics. The Jews had holidays that turned up out of the blue and the Catholics had children in much the same way." Graham's gay lover complicates things, as does Betty's affair with her father-in-law, but Smut is really no saucier than everything Bennett writes. Remember the flurried housemaster in Forty Years On complaining "I wish I could put my hands on the choir's parts".

No need to rack your brains. It's in the boxed Three Plays edition (£30.60), with Bennett as headmaster every bit as good as Gielgud on stage, along with An Englishman Abroad and Kafka's Dick. The Englishman is Guy Burgess exiled in Moscow. It's the true story told to Bennett by Coral Browne, who met Burgess when the Old Vic took Hamlet to the USSR in 1958. He asked her to bring a tape measure to his drab, utilitarian flat and order him some new suits from his London tailor. Michael Gambon and Penelope Wilton both won Baftas for their performances in this radio adaptation. And Jim Broadbent should have got one for the World Service production of The Madness of George III (£13.25), on which Colin Firth must have based his King's Speech triumph.

My all-time favourite Bennett story is The Uncommon Reader (£13.25), about the Queen discovering the joy of reading, everywhere – at meals, corgi-walking, even in the state coach: "She'd got quite good at reading and waving, the trick being to keep the book below the level of the window and to keep focused on it and not on the crowds." Only Bennett, in Children's Classics (£35 boxed set), could keep Pooh, Alice and Toad on the right side of whimsy. His Diaries (£20.40) are frank and very funny, and all serious Bennett buffs will want the only surviving episode (thanks to Auntie's tape-recycling policy) of his 1966 TV series On the Margin (£9.25), which includes the famous "NORWICH" knickers telegram. Good listening.

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Alan Bennett

Re: Alan Bennett

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOsYN---eGk

Take A Pew- Alan Bennett's sermon from Beyond the Fringe.

Early AB monologue from Beyond the Fringe.

Bennett had stated in his application for University that he intended to pursue a career in the Church after graduation. Nothing came of this ambition, but his annually-published diaries are full of accounts of visits to country churches where he inspects the medieval rood screen before enjoying his delicious sandwiches in the churchyard.

His last public pronouncement on the matter was that he didn't know whether he believed in God or not. For all that, he still has a certain indefinably clerical air about him.

Take A Pew- Alan Bennett's sermon from Beyond the Fringe.

Early AB monologue from Beyond the Fringe.

Bennett had stated in his application for University that he intended to pursue a career in the Church after graduation. Nothing came of this ambition, but his annually-published diaries are full of accounts of visits to country churches where he inspects the medieval rood screen before enjoying his delicious sandwiches in the churchyard.

His last public pronouncement on the matter was that he didn't know whether he believed in God or not. For all that, he still has a certain indefinably clerical air about him.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Alan Bennett

Re: Alan Bennett

The Guardian profile: Alan Bennett

He has been called everything from national treasure and prose laureate to curmudgeon laureate and Oracle of Little England. Yet the difference between Bennett the man and Bennett the image remains an enigma

Aida Edemariam The Guardian, Friday 14 May 2004 15.00 BST

He is, according to the papers, a national treasure. Also a "national teddy bear" (Francis Wheen), "prose laureate" (David Thomson), "curmudgeon laureate" (Mark Jones), and Oracle of Little England (Matthew Norman).

Alan Bennett's new play, The History Boys, is previewing at the National (and still, apparently, being rewritten) so the attempted canonisations have begun again. Last week he became the Bard of British Loneliness which, says Nicholas Hytner, who is directing, "caused us all a great deal of merriment".

Michael Frayn, no stranger to fame himself, tells a story of his youngest daughter, at about 15, asking him "in an exasperated way, 'Why can't you be famous, dad, like Alan Bennett?'" It's partly, says Frayn, who did national service with Bennett and has been a friend ever since, because Bennett has always been a performer as well as a writer, appearing on TV, on stage. Partly it's because he is "incapable of writing a dull line", says Hytner (who's directing a Bennett premiere for the fifth time). "There's his feel for dialogue, and, more particularly, his feel for the workings of the mind and heart, and how they're related. That's why he is so trusted and respected by the audience. They know they're not going to be dicked around."

But there is more to it than this. In mid-June, Bennett, who turned 70 on Sunday, will be appearing at the Royal Festival Hall as part of the Meltdown festival. He was invited to perform by this year's curator, Morrissey, who counts the playwright as one of his idols. Morrissey's biographer, Mark Simpson, suspects that he admires "Bennett's Englishness (really a form of northerness), which is funny, self-mocking, stubborn, sharp and anti-Establishment." It's as though Bennett provides for his fans a particular, alternative, national identity.

The little that we know about The History Boys is that it is set in a school, among sixth-formers studying English and history. Thirty-six years ago Bennett's first play, Forty Years On, was also set in a school, Albion House, a minor southern public school that serves as "a loose metaphor for England". It began with a speech by the outgoing headmaster that's typical Bennett: high pomp quickly undercut by bathos, often related to bodily functions.

His only other historical play, The Madness of King George III (1991), may be about royalty, but it turns on the contents of a chamberpot.

Forty Years On contains many schoolboy jokes, Bennett's trademark slick one-liners. "Mark my words," says the headmaster, "when a society has to resort to the lavatory for its humour, the writing is on the wall." But the headmaster is not entirely a figure of fun. He stands for "a kind of constructed nostalgia," says Frayn, "for an England Bennett had never known, and in a part of society he would never have been part of even if he had been alive. It's one of the things that makes the play interesting, that it's both for this traditional England, and mocking it at the same time."

Forty Years On, with John Gielgud as headmaster, was a West End hit. It was followed by some more naturalistic plays, the Kafka plays, the spy plays, and much TV, which all, except for the occasional hiccup, did well; many feel, however, that the Talking Heads series of monologues (1988 and 1998) is his best work. Now taught at A Level, and the most successful talking books of all time, they hoisted Bennett to an entirely different level of fame. And they are about another kind of England altogether.

Bennett was born and grew up in Leeds, where his father was a butcher and amateur musician; his parents, funny and quick at home, were self-effacing, uneasy in public. Bennett soon learned the Larkin-esque lesson "that life is generally something that happens elsewhere", and the Talking Heads are set where life, by this assessment, doesn't happen: country vicarages, suburbs.

Most feature women, and while the stories differ, the loved, but guilt-inducing figure of Bennett's mother, who suffered Alzheimer's and died in a home, hovers over much of his work. The monologues, awash in regret and disappointment, are tragic, claustrophobic and very funny. "I think they are a real artistic development," says Frayn. "It's the finest thing you can do as a writer, to get the material down to absolutely the living nerve, the heart of the work, and nothing else at all."

Bennett escaped via Cambridge, briefly, and Oxford, where for a while he became a history don, and then through Beyond the Fringe. Though in his autobiographical collection, Writing Home, he is quick to qualify his parents' assumption that "education was a passport to social ease" - "it was class and temperament, not want of education, that held their tongues" - the point remains that while education may not make you better at parties, it means far more than how much you know.

Among the many things that horrified him about the Thatcher regime was student loans: he knew that he, and other grammar school boys, such as Frayn, were given a future by not having to pay for university. One hears The History Boys may be set in the early 80s; it would be surprising if this were not at least mentioned. Bennett is not, at the moment, much happier with Blair than he was with Thatcher.

In A Shameful Year, his latest annual diary in the London Review of Books, he revealed that, after a non-marching lifetime (except once, by accident), he had marched twice against the invasion of Iraq.

Mary-Kay Wilmers, editor of the LRB and a long-time neighbour, characterises his position as consistent with his strong anti-appeasement views of the second-world war: the Suez crisis and this Gulf war, he feels, are blatant misuses of the anti-appeasement argument. He was taken to task by John Lloyd, and called a "hysterical schoolgirl" by another reader. Wilmers sees nothing unusual in this: "Infantile is always the adjective applied to the left by its critics; it's used of him and it's used by people writing to the paper to cancel their subscriptions."

There is a central, much-stated paradox to Bennett: he refuses to be interviewed, and yet so much of his work is personal (not to mention Writing Home, which runs to 612 pages). This creates a hall of mirrors in which he seems both known and unknown. An incident during the run of The Lady in the Van, in which he appears, avec doppelganger, is characteristic: one night, Bennett 1 (Nicholas Farrell) was indisposed, so Bennett stepped in as himself. Kevin McNally (Bennett 2) later confided to the BBC that "he's not a very good Alan Bennett, actually". There is a well-tended hedge dividing Bennett the image from Bennett the man.

In a diary entry for August 10, 1994, he remembered being bored by Stephen Spender retelling stories he'd already published: "There's very little in the back of the shop is the message: now it's all out on the shelves, the best plan is to pipe down." In 1993, the New Yorker had discovered that there was more in the back of the shop than anyone, even close friends, suspected: Bennett had been having a relationship with Anne Davies, originally his cleaning lady, for over 10 years.

This despite a 1987 demand from Ian McKellen that he declare whether he was gay. Bennett famously retorted that this was like asking a man crawling across the Sahara whether he would prefer Perrier or Malvern water. "I was rather pleased with that," said Bennett later. "It put him in his place as well." Which perhaps tells us more about Bennett than the existence or otherwise of a sex life. He now lives with Rupert Thomas, editor of World of Interiors.

Bennett has been known to complain that he is not taken as seriously as some of his peers, and a 1998 National Theatre ranking of the century's greatest playwrights didn't even place him in the top 20. There is, of course, the worry that, fairly or otherwise, has always dogged him - that he can't resist a joke. But the critic David Thomson, an admirer of Bennett's, sees something more.

"I think his vision is very local in terms of place and time and class. He's absolutely brilliant at getting the wistful collapse of a certain kind of British middle-class sensibility, but when that feeling has passed, people may look back and say, 'What was that about?' I'm not sure he will travel in time, because I'm not sure his work is about more than a certain kind of refined eloquence, a very touching self-pity."

And he worries that the plays lack the increasing moral indignation evident in Bennett's diaries, for example, "an anger about the way England has gone. Maybe the new play will be a revelation".

In his well-modulated tetchiness about property developers, cars, Classic FM, Bennett is increasingly coming to resemble his headmaster in 40 Years On. Yet the further paradox is that in the headmaster's nostalgia for a lost England, there rings a very contemporary note: "To let: A valuable site at the cross-roads of the world. At present on offer to European clients. Outlying portions of the estate already disposed of to sitting tenants. Of some historical and period interest. Some alterations and improvements necessary."

Life in short

Born May 9 1934

Education Leeds Modern school; Oxford University

Career Theatre includes: Beyond the Fringe (Royal Lyceum Edinburgh 1960, Fortune London 1961, NYC 1962); Forty Years On (Apollo) 1968, Getting On (Queen's) 1971, Habeas Corpus (Lyric) 1973, Kafka's Dick (Royal Court) 1986, An Englishman Abroad (also dir, NT) 1988, Wind in the Willows (adaptation, RNT) 1990, The Madness of George III (RNT) 1991-93, The Lady in the Van 1999

Television includes: On the Margin (series) 1966, A Day Out 1972, Sunset Across the Bay 1975, A Little Outing, A Visit from Miss Prothero 1977, Doris and Doreen 1978, One Fine Day 1979, The Insurance Man 1986, Talking Heads (series) 1988

Films include: A Private Function 1984, Prick Up Your Ears 1987, The Madness of King George 1995

Books include: Forty Years On 1969, Getting On 1972, Writing Home 1994,Telling Tales 2000

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

He has been called everything from national treasure and prose laureate to curmudgeon laureate and Oracle of Little England. Yet the difference between Bennett the man and Bennett the image remains an enigma

Aida Edemariam The Guardian, Friday 14 May 2004 15.00 BST

He is, according to the papers, a national treasure. Also a "national teddy bear" (Francis Wheen), "prose laureate" (David Thomson), "curmudgeon laureate" (Mark Jones), and Oracle of Little England (Matthew Norman).

Alan Bennett's new play, The History Boys, is previewing at the National (and still, apparently, being rewritten) so the attempted canonisations have begun again. Last week he became the Bard of British Loneliness which, says Nicholas Hytner, who is directing, "caused us all a great deal of merriment".

Michael Frayn, no stranger to fame himself, tells a story of his youngest daughter, at about 15, asking him "in an exasperated way, 'Why can't you be famous, dad, like Alan Bennett?'" It's partly, says Frayn, who did national service with Bennett and has been a friend ever since, because Bennett has always been a performer as well as a writer, appearing on TV, on stage. Partly it's because he is "incapable of writing a dull line", says Hytner (who's directing a Bennett premiere for the fifth time). "There's his feel for dialogue, and, more particularly, his feel for the workings of the mind and heart, and how they're related. That's why he is so trusted and respected by the audience. They know they're not going to be dicked around."

But there is more to it than this. In mid-June, Bennett, who turned 70 on Sunday, will be appearing at the Royal Festival Hall as part of the Meltdown festival. He was invited to perform by this year's curator, Morrissey, who counts the playwright as one of his idols. Morrissey's biographer, Mark Simpson, suspects that he admires "Bennett's Englishness (really a form of northerness), which is funny, self-mocking, stubborn, sharp and anti-Establishment." It's as though Bennett provides for his fans a particular, alternative, national identity.

The little that we know about The History Boys is that it is set in a school, among sixth-formers studying English and history. Thirty-six years ago Bennett's first play, Forty Years On, was also set in a school, Albion House, a minor southern public school that serves as "a loose metaphor for England". It began with a speech by the outgoing headmaster that's typical Bennett: high pomp quickly undercut by bathos, often related to bodily functions.

His only other historical play, The Madness of King George III (1991), may be about royalty, but it turns on the contents of a chamberpot.

Forty Years On contains many schoolboy jokes, Bennett's trademark slick one-liners. "Mark my words," says the headmaster, "when a society has to resort to the lavatory for its humour, the writing is on the wall." But the headmaster is not entirely a figure of fun. He stands for "a kind of constructed nostalgia," says Frayn, "for an England Bennett had never known, and in a part of society he would never have been part of even if he had been alive. It's one of the things that makes the play interesting, that it's both for this traditional England, and mocking it at the same time."

Forty Years On, with John Gielgud as headmaster, was a West End hit. It was followed by some more naturalistic plays, the Kafka plays, the spy plays, and much TV, which all, except for the occasional hiccup, did well; many feel, however, that the Talking Heads series of monologues (1988 and 1998) is his best work. Now taught at A Level, and the most successful talking books of all time, they hoisted Bennett to an entirely different level of fame. And they are about another kind of England altogether.

Bennett was born and grew up in Leeds, where his father was a butcher and amateur musician; his parents, funny and quick at home, were self-effacing, uneasy in public. Bennett soon learned the Larkin-esque lesson "that life is generally something that happens elsewhere", and the Talking Heads are set where life, by this assessment, doesn't happen: country vicarages, suburbs.

Most feature women, and while the stories differ, the loved, but guilt-inducing figure of Bennett's mother, who suffered Alzheimer's and died in a home, hovers over much of his work. The monologues, awash in regret and disappointment, are tragic, claustrophobic and very funny. "I think they are a real artistic development," says Frayn. "It's the finest thing you can do as a writer, to get the material down to absolutely the living nerve, the heart of the work, and nothing else at all."

Bennett escaped via Cambridge, briefly, and Oxford, where for a while he became a history don, and then through Beyond the Fringe. Though in his autobiographical collection, Writing Home, he is quick to qualify his parents' assumption that "education was a passport to social ease" - "it was class and temperament, not want of education, that held their tongues" - the point remains that while education may not make you better at parties, it means far more than how much you know.

Among the many things that horrified him about the Thatcher regime was student loans: he knew that he, and other grammar school boys, such as Frayn, were given a future by not having to pay for university. One hears The History Boys may be set in the early 80s; it would be surprising if this were not at least mentioned. Bennett is not, at the moment, much happier with Blair than he was with Thatcher.

In A Shameful Year, his latest annual diary in the London Review of Books, he revealed that, after a non-marching lifetime (except once, by accident), he had marched twice against the invasion of Iraq.

Mary-Kay Wilmers, editor of the LRB and a long-time neighbour, characterises his position as consistent with his strong anti-appeasement views of the second-world war: the Suez crisis and this Gulf war, he feels, are blatant misuses of the anti-appeasement argument. He was taken to task by John Lloyd, and called a "hysterical schoolgirl" by another reader. Wilmers sees nothing unusual in this: "Infantile is always the adjective applied to the left by its critics; it's used of him and it's used by people writing to the paper to cancel their subscriptions."

There is a central, much-stated paradox to Bennett: he refuses to be interviewed, and yet so much of his work is personal (not to mention Writing Home, which runs to 612 pages). This creates a hall of mirrors in which he seems both known and unknown. An incident during the run of The Lady in the Van, in which he appears, avec doppelganger, is characteristic: one night, Bennett 1 (Nicholas Farrell) was indisposed, so Bennett stepped in as himself. Kevin McNally (Bennett 2) later confided to the BBC that "he's not a very good Alan Bennett, actually". There is a well-tended hedge dividing Bennett the image from Bennett the man.

In a diary entry for August 10, 1994, he remembered being bored by Stephen Spender retelling stories he'd already published: "There's very little in the back of the shop is the message: now it's all out on the shelves, the best plan is to pipe down." In 1993, the New Yorker had discovered that there was more in the back of the shop than anyone, even close friends, suspected: Bennett had been having a relationship with Anne Davies, originally his cleaning lady, for over 10 years.

This despite a 1987 demand from Ian McKellen that he declare whether he was gay. Bennett famously retorted that this was like asking a man crawling across the Sahara whether he would prefer Perrier or Malvern water. "I was rather pleased with that," said Bennett later. "It put him in his place as well." Which perhaps tells us more about Bennett than the existence or otherwise of a sex life. He now lives with Rupert Thomas, editor of World of Interiors.

Bennett has been known to complain that he is not taken as seriously as some of his peers, and a 1998 National Theatre ranking of the century's greatest playwrights didn't even place him in the top 20. There is, of course, the worry that, fairly or otherwise, has always dogged him - that he can't resist a joke. But the critic David Thomson, an admirer of Bennett's, sees something more.

"I think his vision is very local in terms of place and time and class. He's absolutely brilliant at getting the wistful collapse of a certain kind of British middle-class sensibility, but when that feeling has passed, people may look back and say, 'What was that about?' I'm not sure he will travel in time, because I'm not sure his work is about more than a certain kind of refined eloquence, a very touching self-pity."

And he worries that the plays lack the increasing moral indignation evident in Bennett's diaries, for example, "an anger about the way England has gone. Maybe the new play will be a revelation".

In his well-modulated tetchiness about property developers, cars, Classic FM, Bennett is increasingly coming to resemble his headmaster in 40 Years On. Yet the further paradox is that in the headmaster's nostalgia for a lost England, there rings a very contemporary note: "To let: A valuable site at the cross-roads of the world. At present on offer to European clients. Outlying portions of the estate already disposed of to sitting tenants. Of some historical and period interest. Some alterations and improvements necessary."

Life in short

Born May 9 1934

Education Leeds Modern school; Oxford University

Career Theatre includes: Beyond the Fringe (Royal Lyceum Edinburgh 1960, Fortune London 1961, NYC 1962); Forty Years On (Apollo) 1968, Getting On (Queen's) 1971, Habeas Corpus (Lyric) 1973, Kafka's Dick (Royal Court) 1986, An Englishman Abroad (also dir, NT) 1988, Wind in the Willows (adaptation, RNT) 1990, The Madness of George III (RNT) 1991-93, The Lady in the Van 1999

Television includes: On the Margin (series) 1966, A Day Out 1972, Sunset Across the Bay 1975, A Little Outing, A Visit from Miss Prothero 1977, Doris and Doreen 1978, One Fine Day 1979, The Insurance Man 1986, Talking Heads (series) 1988

Films include: A Private Function 1984, Prick Up Your Ears 1987, The Madness of King George 1995

Books include: Forty Years On 1969, Getting On 1972, Writing Home 1994,Telling Tales 2000

guardian.co.uk © Guardian News and Media Limited 2011

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Alan Bennett

Re: Alan Bennett

...and The Independent's Alan Bennett Prolile:

*******************************************************************************

Alan Bennett: Almost forty years on

With a new play, 'The History Boys', the former Beyond the Fringe star returns to the subject of education, 39 years after the National Theatre staged the work that made his name as a dramatist. Approaching 70, the master of minutiae is as acute as ever

By Alex Games

Sunday, 2 May 2004

A flurry of letters followed the publication of Alan Bennett's annual diary in the London Review of Books last December. His output has been irregular of late, so Bennett fans must have been relieved to see him back: a portent, perhaps, of his return to the National Theatre later this month with The History Boys, his first new play since The Lady in the Van. Bennett commented on Bush and Blair's frequent phrase "Our patience is exhausted", and said that Hitler used to say the same thing. Two weeks later, in the LRB, the writer John Lloyd described Bennett, at length, as "shameful". Another letter said, more tersely, that "his diary displays the political outlook of a hysterical schoolgirl".

The end-of-year diary by Bennett, who will be 70 next Sunday, draws together many threads. The History Boys should bring together some familiar strands too. The plot involves "an unruly bunch of bright, funny sixth-form boys in pursuit of sex, sport and a place at university". The head-teacher, quoted in the publicity, says: "School gives them an education. I give them the wherewithal to resist it." The parallels are not hard to find. The words "Spontaneous? Then it must be stopped at once" were spoken by the headmaster in Bennett's first stage play, Forty Years On, which opened not quite 40 years ago, in 1968. Both plays are set in a school. Has Bennett come full circle, or did he never, actually, move that far away?

There is some truth to both views. Forty Years On was a marvellous ragbag of smutty schoolboy jokes and nostalgia for an Edwardian England that had all but disappeared. It was also a continuation of the literary flowering that broke out when he escaped - with some relief - from the three other virtuosi of Beyond The Fringe, Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller and Dudley Moore.

Bennett found other voices before he found his own. The quavering sermon was one brilliant impersonation, which he followed with a sackful of TV and stage plays that demonstrated an acute ear for dialogue and an uncanny knack for finding the sublime in the banal. He played the fame game, too. In the account of a day in Oxford in his 2003 diary, he describes having to whip out his Camden bus pass to identify himself to a junior proctor. "Andrew (A N) Wilson sails through unchallenged," he notes. But it is the fact that he draws this to our attention which commands interest, and even admiration. No one undermines Bennett better than Bennett. One benefit of travelling incognito is to hear so many unguarded comments.

Of course, with Bennett as his only official biographer, whatever he says, goes. There is evidence that he entered heartily into college life, though little from the man himself. His great, mostly lost, BBC2 series from 1966 was, characteristically, called On The Margin. If the Fringe quartet were the comic equivalent of the Beatles, this was comparable to George Harrison recording a brilliant solo album.

Bennett's response to the humiliations of the Fringe has been his long list of writing and performing credits, delivered with that Protestant work ethic which forever drives a lapsed teenage believer. And yet, despite becoming one of the most successful writers that Britain - let alone Leeds Modern Grammar School - has ever produced, Bennett is not immune to peer-group rivalry. Compared to playwrights such as Stoppard, Pinter, Edgar and Hare, he sometimes complains, in a bemused way, that his plays have not been accorded quite the same level of literary appreciation. Are his plays, perhaps, too funny to be treated seriously? Bennett acknowledges that he could never resist a good pun. Most people, of course, couldn't create one in the first place.

And yet, when he was finally offered an honorary degree by Oxford, he rejected it on the grounds that his alma mater had accepted a chair in the name of Rupert Murdoch. There's no pleasing some people.

Sometimes described as "woolly", his political views have always reflected the conservatism of an Old Labour voter. Few could disagree that library closures are shameful; ditto the opening of Starbucks in beautiful Primrose Hill, or that the BBC under John Birt was streamlined for efficiency but not fertility. On other matters, though, he appeared less sure. Sexually, for example, being half-in and half-out didn't help him to get a date, and the years of being in the shadow of such sexual athletes as Dudley Moore took their toll.

Which way to jump vexed him for a long time, and the public must have been mildly curious, but in 1993 he told The New Yorker that he had been having a secret affair with his cleaning lady for 14 years. What was remarkable was how few of his close friends had any idea. He now lives his life, divided between homes in Camden and Yorkshire, with a male partner.

Bennett's hostility to the press peaked with his eulogy for his friend Russell Harty, when he railed against the News of the World for hounding a dying man. On a much smaller scale, though, the steady stream of pithy allusions to his own friends in Bennett's diaries reveal a man who knows the value of a news-bite, but much prefers to do his own biting. He resents being treated by anyone as "public property", but he knows how to get his message out to the media when he needs to.

His portrayal of the madness of George III was a valuable contribution to the discussion on the inherited condition of porphyria, and his imagined encounter between the Queen and her art expert (and former Russian spy) Sir Anthony Blunt was a comic tour de force. But any reputation for cosiness needs to be re-examined. When he adapted the screenplay of John Lahr's biography of Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell, Prick Up Your Ears, it contained cottaging scenes in public toilets that were considered shocking at the time. Eight years earlier, in 1979, he had collaborated with the godfather of left-wing theatre, Lindsay Anderson, in a TV play called The Old Crowd, which self-consciously revealed cameras and crew filming the actors. Middle England rose up to complain: the very people who were so disarmed by the tender, suffocating monologues of Talking Heads (1987) that they clutched Bennett to their hearts and - whether he liked it or not - never let him go.

Bennett's ambivalence seems to match the English psyche, like the southern gentility of John Betjeman or the northern bluntness of J B Priestley. Spanning both worlds (as did Priestley), he is master of both but at home in neither. The setting for his play The Old Country, eventually revealed as Soviet Russia, was not that far from the middle-class comfort zone where an earlier play, Getting On, was set. Bennett is never one to move the scenery too much, even when, as in his humorous short story The Clothes They Stood Up In, the joke concerns a middle-aged couple who come home to find their entire house stripped of every single item.

But this denuding was not the prelude to an ending of high drama: Bennett likes jokes too much. Further letters to the LRB about his 2003 diary refer to Kennedy's Revised Latin Primer, Kettle's Yard art gallery in Cambridge and the sheepfolds on the moor road near Brough. We take from Alan Bennett whatever we need for our own purposes. And there is always, it would seem, enough to go round.

*******************************************************************************

Alan Bennett: Almost forty years on

With a new play, 'The History Boys', the former Beyond the Fringe star returns to the subject of education, 39 years after the National Theatre staged the work that made his name as a dramatist. Approaching 70, the master of minutiae is as acute as ever

By Alex Games

Sunday, 2 May 2004

A flurry of letters followed the publication of Alan Bennett's annual diary in the London Review of Books last December. His output has been irregular of late, so Bennett fans must have been relieved to see him back: a portent, perhaps, of his return to the National Theatre later this month with The History Boys, his first new play since The Lady in the Van. Bennett commented on Bush and Blair's frequent phrase "Our patience is exhausted", and said that Hitler used to say the same thing. Two weeks later, in the LRB, the writer John Lloyd described Bennett, at length, as "shameful". Another letter said, more tersely, that "his diary displays the political outlook of a hysterical schoolgirl".

The end-of-year diary by Bennett, who will be 70 next Sunday, draws together many threads. The History Boys should bring together some familiar strands too. The plot involves "an unruly bunch of bright, funny sixth-form boys in pursuit of sex, sport and a place at university". The head-teacher, quoted in the publicity, says: "School gives them an education. I give them the wherewithal to resist it." The parallels are not hard to find. The words "Spontaneous? Then it must be stopped at once" were spoken by the headmaster in Bennett's first stage play, Forty Years On, which opened not quite 40 years ago, in 1968. Both plays are set in a school. Has Bennett come full circle, or did he never, actually, move that far away?

There is some truth to both views. Forty Years On was a marvellous ragbag of smutty schoolboy jokes and nostalgia for an Edwardian England that had all but disappeared. It was also a continuation of the literary flowering that broke out when he escaped - with some relief - from the three other virtuosi of Beyond The Fringe, Peter Cook, Jonathan Miller and Dudley Moore.

Bennett found other voices before he found his own. The quavering sermon was one brilliant impersonation, which he followed with a sackful of TV and stage plays that demonstrated an acute ear for dialogue and an uncanny knack for finding the sublime in the banal. He played the fame game, too. In the account of a day in Oxford in his 2003 diary, he describes having to whip out his Camden bus pass to identify himself to a junior proctor. "Andrew (A N) Wilson sails through unchallenged," he notes. But it is the fact that he draws this to our attention which commands interest, and even admiration. No one undermines Bennett better than Bennett. One benefit of travelling incognito is to hear so many unguarded comments.

Of course, with Bennett as his only official biographer, whatever he says, goes. There is evidence that he entered heartily into college life, though little from the man himself. His great, mostly lost, BBC2 series from 1966 was, characteristically, called On The Margin. If the Fringe quartet were the comic equivalent of the Beatles, this was comparable to George Harrison recording a brilliant solo album.

Bennett's response to the humiliations of the Fringe has been his long list of writing and performing credits, delivered with that Protestant work ethic which forever drives a lapsed teenage believer. And yet, despite becoming one of the most successful writers that Britain - let alone Leeds Modern Grammar School - has ever produced, Bennett is not immune to peer-group rivalry. Compared to playwrights such as Stoppard, Pinter, Edgar and Hare, he sometimes complains, in a bemused way, that his plays have not been accorded quite the same level of literary appreciation. Are his plays, perhaps, too funny to be treated seriously? Bennett acknowledges that he could never resist a good pun. Most people, of course, couldn't create one in the first place.

And yet, when he was finally offered an honorary degree by Oxford, he rejected it on the grounds that his alma mater had accepted a chair in the name of Rupert Murdoch. There's no pleasing some people.

Sometimes described as "woolly", his political views have always reflected the conservatism of an Old Labour voter. Few could disagree that library closures are shameful; ditto the opening of Starbucks in beautiful Primrose Hill, or that the BBC under John Birt was streamlined for efficiency but not fertility. On other matters, though, he appeared less sure. Sexually, for example, being half-in and half-out didn't help him to get a date, and the years of being in the shadow of such sexual athletes as Dudley Moore took their toll.

Which way to jump vexed him for a long time, and the public must have been mildly curious, but in 1993 he told The New Yorker that he had been having a secret affair with his cleaning lady for 14 years. What was remarkable was how few of his close friends had any idea. He now lives his life, divided between homes in Camden and Yorkshire, with a male partner.

Bennett's hostility to the press peaked with his eulogy for his friend Russell Harty, when he railed against the News of the World for hounding a dying man. On a much smaller scale, though, the steady stream of pithy allusions to his own friends in Bennett's diaries reveal a man who knows the value of a news-bite, but much prefers to do his own biting. He resents being treated by anyone as "public property", but he knows how to get his message out to the media when he needs to.

His portrayal of the madness of George III was a valuable contribution to the discussion on the inherited condition of porphyria, and his imagined encounter between the Queen and her art expert (and former Russian spy) Sir Anthony Blunt was a comic tour de force. But any reputation for cosiness needs to be re-examined. When he adapted the screenplay of John Lahr's biography of Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell, Prick Up Your Ears, it contained cottaging scenes in public toilets that were considered shocking at the time. Eight years earlier, in 1979, he had collaborated with the godfather of left-wing theatre, Lindsay Anderson, in a TV play called The Old Crowd, which self-consciously revealed cameras and crew filming the actors. Middle England rose up to complain: the very people who were so disarmed by the tender, suffocating monologues of Talking Heads (1987) that they clutched Bennett to their hearts and - whether he liked it or not - never let him go.

Bennett's ambivalence seems to match the English psyche, like the southern gentility of John Betjeman or the northern bluntness of J B Priestley. Spanning both worlds (as did Priestley), he is master of both but at home in neither. The setting for his play The Old Country, eventually revealed as Soviet Russia, was not that far from the middle-class comfort zone where an earlier play, Getting On, was set. Bennett is never one to move the scenery too much, even when, as in his humorous short story The Clothes They Stood Up In, the joke concerns a middle-aged couple who come home to find their entire house stripped of every single item.

But this denuding was not the prelude to an ending of high drama: Bennett likes jokes too much. Further letters to the LRB about his 2003 diary refer to Kennedy's Revised Latin Primer, Kettle's Yard art gallery in Cambridge and the sheepfolds on the moor road near Brough. We take from Alan Bennett whatever we need for our own purposes. And there is always, it would seem, enough to go round.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Alan Bennett

Re: Alan Bennett

Alan Bennett drops in for tea with Occupy London protesters

Playwright – no stranger to political engagement – leaves signed copies of books at camp's literary tent

Hannah Godfrey

The Guardian, Saturday 26 November 2011

Alan Bennett took tea with activists at the Occupy London camp on Friday, leaving signed copies of The History Boys and A Life Like Other People's. Photograph: Scoopt/Getty Images

Alan Bennett has added his weight to the Occupy London protest by paying a visit to the encampment outside St Paul's Cathedral.

The playwright took tea with activists on Friday, and left two signed copies of his work at the camp's library tent.

The books – which he dedicated "To Occupy London" – were The History Boys and his family memoir, A Life Like Other People's.

Last week the fashion designer Vivienne Westwood addressed protesters, telling them that what they were doing was "wonderful".

Other public figures to have visited the camp have included WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and Radiohead's Thom Yorke.

Bennett is no stranger to political engagement. He described austerity-driven plans to close libraries as "child abuse" and earlier this year joined Zadie Smith and Philip Pullman in the campaign to save a London library – opened by Mark Twain in 1900 – from closure.

Activists have been camped in the churchyard of St Paul's Cathedral since 15 October. Last week the Corporation of London served an eviction notice on Occupy London for obstructing the public highway. A hearing is due to begin at the High Court on 19 December, with protesters vowing to fight any moves to be forced to close the camp.

Playwright – no stranger to political engagement – leaves signed copies of books at camp's literary tent

Hannah Godfrey

The Guardian, Saturday 26 November 2011

Alan Bennett took tea with activists at the Occupy London camp on Friday, leaving signed copies of The History Boys and A Life Like Other People's. Photograph: Scoopt/Getty Images

Alan Bennett has added his weight to the Occupy London protest by paying a visit to the encampment outside St Paul's Cathedral.

The playwright took tea with activists on Friday, and left two signed copies of his work at the camp's library tent.

The books – which he dedicated "To Occupy London" – were The History Boys and his family memoir, A Life Like Other People's.

Last week the fashion designer Vivienne Westwood addressed protesters, telling them that what they were doing was "wonderful".

Other public figures to have visited the camp have included WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange and Radiohead's Thom Yorke.

Bennett is no stranger to political engagement. He described austerity-driven plans to close libraries as "child abuse" and earlier this year joined Zadie Smith and Philip Pullman in the campaign to save a London library – opened by Mark Twain in 1900 – from closure.

Activists have been camped in the churchyard of St Paul's Cathedral since 15 October. Last week the Corporation of London served an eviction notice on Occupy London for obstructing the public highway. A hearing is due to begin at the High Court on 19 December, with protesters vowing to fight any moves to be forced to close the camp.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: Alan Bennett

Re: Alan Bennett

The Madness of George III – review

Apollo, London

Lyn Gardner

guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 24 January 2012 18.59 GMT

A big, compassionate heart … David Haig (front) and Clive Francis in The Madness of George III Photograph: Tristram Kenton Photograph: Tristram Kenton for the Guardian

"Lobsters crack my bones," cries the mad, tormented king. It could be Shakespeare's King Lear, but it's actually Alan Bennett King George (David Haig) whose bouts of porphyria caused his urine to turn blue and turned his mind from reason. He had already lost the American colonies, loses all his dignity as baffled doctors torture both body and mind, and he is in danger of losing the crown, too, as the government of William Pitt (Nicholas Rowe) wobbles and opposition leader Charles Fox (Gary Oliver) connives to have the foolish Prince of Wales (Christopher Keegan) declared Regent.

Bennett's play owes a considerable debt to Shakespeare's tragedy, and it acknowledges this in a most affecting way as the king, newly restored to health, reads Lear with his devoted equerry (Orlando James), his doctor (Clive Francis) and Pitt. "Awfully good stuff," he says happily.

Awfully good stuff it is, indeed, in Christopher Luscombe's clever revival. With help from Janet Bird's design, with its rows of empty picture frames suspended above the stage, it reminds us that Bennett is not writing a royal Downton Abbey, but a play exploring appearance and reality. The entire edifice of court, government and country is based on an illusion: the danger lies not in the king's madness, but in the revelation that the poor, shivering creature sitting blistered, bled, purged and wrapped in a straitjacket, is only a man after all.

He may be a monarch who calls his wife (Beatie Edney) "Mrs King" and dreams of an ordinary life together, but he knows that image is all. "I have always been myself, even when I was ill, but now I seem myself," he points out to those who express pleasure at finding him more himself. The difference between him and his son, George, is expressed not just in what they do, but how they look: as the king is laced into a straitjacket, the Prince of Wales is laced into a corset until he oozes like an over-stuffed meat pie.

There are times when the evening feels a little schematic, and the dialogue forced, but this is intelligent, witty and moving West End fare with a big, compassionate heart. It features a most extraordinary performance from David Haig, an actor who radiates sweetness, terror, comedy and tragedy, often in the same line. The play is everything because of him.

Apollo, London

Lyn Gardner

guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 24 January 2012 18.59 GMT

A big, compassionate heart … David Haig (front) and Clive Francis in The Madness of George III Photograph: Tristram Kenton Photograph: Tristram Kenton for the Guardian

"Lobsters crack my bones," cries the mad, tormented king. It could be Shakespeare's King Lear, but it's actually Alan Bennett King George (David Haig) whose bouts of porphyria caused his urine to turn blue and turned his mind from reason. He had already lost the American colonies, loses all his dignity as baffled doctors torture both body and mind, and he is in danger of losing the crown, too, as the government of William Pitt (Nicholas Rowe) wobbles and opposition leader Charles Fox (Gary Oliver) connives to have the foolish Prince of Wales (Christopher Keegan) declared Regent.

Bennett's play owes a considerable debt to Shakespeare's tragedy, and it acknowledges this in a most affecting way as the king, newly restored to health, reads Lear with his devoted equerry (Orlando James), his doctor (Clive Francis) and Pitt. "Awfully good stuff," he says happily.

Awfully good stuff it is, indeed, in Christopher Luscombe's clever revival. With help from Janet Bird's design, with its rows of empty picture frames suspended above the stage, it reminds us that Bennett is not writing a royal Downton Abbey, but a play exploring appearance and reality. The entire edifice of court, government and country is based on an illusion: the danger lies not in the king's madness, but in the revelation that the poor, shivering creature sitting blistered, bled, purged and wrapped in a straitjacket, is only a man after all.

He may be a monarch who calls his wife (Beatie Edney) "Mrs King" and dreams of an ordinary life together, but he knows that image is all. "I have always been myself, even when I was ill, but now I seem myself," he points out to those who express pleasure at finding him more himself. The difference between him and his son, George, is expressed not just in what they do, but how they look: as the king is laced into a straitjacket, the Prince of Wales is laced into a corset until he oozes like an over-stuffed meat pie.

There are times when the evening feels a little schematic, and the dialogue forced, but this is intelligent, witty and moving West End fare with a big, compassionate heart. It features a most extraordinary performance from David Haig, an actor who radiates sweetness, terror, comedy and tragedy, often in the same line. The play is everything because of him.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Similar topics

Similar topics» Alan Turing

» Alan Ayckbourn

» Playwright Alan Plater

» Alan Moore's League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and other matters

» Alan Ayckbourn

» Playwright Alan Plater

» Alan Moore's League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and other matters

Page 1 of 1

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum