The British Empire

3 posters

Page 1 of 1

The British Empire

The British Empire

Empire: What Ruling the World Did to the British by Jeremy Paxman – review

Jeremy Paxman's survey of British imperial rule is sharp and engaging

Bernard Porter

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 5 October 2011 11.30 BST

Onward march: police officers mark independence in the Indian city of Secunderabad. Photograph: Noah Seelam/AFP/Getty Images

Jeremy Paxman thinks we're neglecting the history of the British empire. "Perhaps in the dark recesses of a golf-club bar some harrumphing voice mutters about how much better the world seemed to turn when a great-uncle in baggy shorts ran a patch of Africa the size of Lancashire. But, by and large, no one has much to say about empire." That will come as a surprise to the authors of the dozen fat books about it that have appeared over the last few years. If Paxman thinks his Empire is filling a gap, he's mistaken.

Empire: What Ruling the World Did to the British

by Jeremy Paxman

British imperial history is highly contested territory. One reason is obvious: the number of peoples, societies and nations that still bear the marks of it, or think they do. Another is that it is so often discussed – or expected to be discussed – judgmentally. What readers generally look for first in a new history of the empire is whether it is for it or against it. More neutral books are often forced into one category or the other simply to give reviewers a handle on them; or, if they can't be, they are ignored. For those of us who burrow away at the subject academically, this last is probably the best we can hope for. It's not an option available to Paxman, however, who is too famous to be ignored. In fact it's difficult to say where he stands in the great pro- or anti-imperial debate; but that's to the credit of the book, especially if it can put over to readers that the question is not a simple one.

Judgments come thick and fast, but they are not all on one side. The worst atrocities of British imperial rule are properly highlighted and deplored. The horrors of the slave trade, for example, "should be engraved on the national conscience. It is one of the most disgraceful episodes in British history." Similarly the opium wars, the British reprisals after the Indian mutiny, "genocide" (the right word, he thinks) in Tasmania, the Amritsar massacre, Balfour's perfidy in Palestine, "offering land belonging to one people as a gift to another", the great Bengal famine, the now notorious Kenyan prison camps, and British imperial arrogance and racism generally. Few of the leading "builders" of the British empire – heroes to a previous generation of imperialists – escape Paxman's scorn. The early ones were mostly pirates and freebooters. Clive of India was mainly a fortune-seeker, "scheming, and devious in business". General Gordon was "half-cracked". Cecil Rhodes was "the most sabre-toothed of all empire-builders". Kitchener was a monster. Lawrence of Arabia was romantic, but (again) "half-cracked". Churchill may not have been "quite sane" when it came to India. Lord Meath, the creator of Empire Day, is described as looking "a bit like Father Christmas", with "a bald head, a red face and an enormous white beard"; he had some silly ideas about instilling "duty and discipline" into working-class ne'er-do-wells. (David Cameron might like to look him up.) Others were mostly hypocrites, or "self-deluders" at best. The last includes Gladstone and "more recent moralists in Downing Street".

On the other hand, the book also describes atrocities committed by the colonised in, if anything, even more gory terms: the "Black Hole of Calcutta", for example, "a horror story to rival anything among the Gothic tales which swept Britain" at the time. Paxman isn't too keen on the Mahdi, Gordon's nemesis, either, with his "usual jihadi stuff" and the regime of "slavery, institutionalised paedophilia, hand-loppings and floggings to death" instituted under him. So there's a certain balance here.

More importantly, there was "another side to colonialism". Britain's most admirable imperial agents were her ordinary administrators, who Paxman thinks have been unfairly ridiculed; they were generally good eggs, and – crucially – incorruptible. The British empire was also prone to periodic spasms of moral self-questioning, which is unusual for empires, one of which in the end got rid of slavery. The postwar transition to self-government was managed "peacefully" in the main, though "in a handful of places the British fought nasty little campaigns". (I'm not sure that many Kenyans, Malayans and Cypriots would accept that "little".) Overall, "if you had to live under a foreign government," then the British empire "was better than many of the other possibilities". That "if you had to", however, is a crucial caveat.

If you have to have a popular introduction to British imperial history, too, this book could be said to be better than many of the other possibilities, in particular it is far preferable to Michael Gove's "patriotic" approach. It's a very engaging account, built mainly around dramatic incidents in exotic places (just right for the forthcoming TV series), and the lives of fascinating people, with a good sprinkling of jokes, funny nicknames and sexual references. Paxman makes some very sharp points, and writes well. Here's an example, towards the end: "The British empire had begun with a series of pounces. Then it marched. Next it swaggered. Finally, after wandering aimlessly for a while, it slunk away." If you want the appearance of the whole process described in a few short sentences, I can't imagine it done better.

He doesn't, however, delve much beneath appearances. There's nothing here on the economic, cultural or any other roots of British imperialism. Paxman is insistent that there was no great plan behind it, and that often governments were simply bumped into taking countries without really wanting to. At times he appears to be going along with what he takes to be the 19th-century historian JR Seeley's view, that the empire was accumulated "absent-mindedly". (In fact Seeley said the opposite. Everyone gets this wrong.) To his credit, Paxman repeatedly confesses his own puzzlement: "there was something inherently nonsensical about it … How could the ultimate purpose of colonisation be freedom?" Well, there is an answer to that. He might not agree with it, but he should try to understand it. Dismissing things as "nonsense" is a way of avoiding the bother of explaining them.

In view of the book's subtitle, it's a shame he doesn't say more about what the empire did to the British. He claims it "convinced the British that they were somehow special", but is very woolly about whom he means by "the British" in this context. Later on he claims that it was "mainly a ruling-class thing", with attempts to foist it on "the people" largely unsuccessful. "The noisier the loudspeakers of officialdom, the more reverberant the empty echo." This is hotly disputed in some historical circles, even for the inter-war period, which Paxman is referring to here. If it's true, however, it goes some way to explain the situation which he alleges – and deplores – at the beginning and end of his book: of widespread public amnesia about the old empire, while our prime minister pompously lectures the "lesser breeds" as if he were still wearing those baggy shorts. Hopefully he'll be watching the TV series, too.

Bernard Porter's The Lion's Share: A Short History of British Imperialism is published by Longman.

Jeremy Paxman's survey of British imperial rule is sharp and engaging

Bernard Porter

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 5 October 2011 11.30 BST

Onward march: police officers mark independence in the Indian city of Secunderabad. Photograph: Noah Seelam/AFP/Getty Images

Jeremy Paxman thinks we're neglecting the history of the British empire. "Perhaps in the dark recesses of a golf-club bar some harrumphing voice mutters about how much better the world seemed to turn when a great-uncle in baggy shorts ran a patch of Africa the size of Lancashire. But, by and large, no one has much to say about empire." That will come as a surprise to the authors of the dozen fat books about it that have appeared over the last few years. If Paxman thinks his Empire is filling a gap, he's mistaken.

Empire: What Ruling the World Did to the British

by Jeremy Paxman

British imperial history is highly contested territory. One reason is obvious: the number of peoples, societies and nations that still bear the marks of it, or think they do. Another is that it is so often discussed – or expected to be discussed – judgmentally. What readers generally look for first in a new history of the empire is whether it is for it or against it. More neutral books are often forced into one category or the other simply to give reviewers a handle on them; or, if they can't be, they are ignored. For those of us who burrow away at the subject academically, this last is probably the best we can hope for. It's not an option available to Paxman, however, who is too famous to be ignored. In fact it's difficult to say where he stands in the great pro- or anti-imperial debate; but that's to the credit of the book, especially if it can put over to readers that the question is not a simple one.

Judgments come thick and fast, but they are not all on one side. The worst atrocities of British imperial rule are properly highlighted and deplored. The horrors of the slave trade, for example, "should be engraved on the national conscience. It is one of the most disgraceful episodes in British history." Similarly the opium wars, the British reprisals after the Indian mutiny, "genocide" (the right word, he thinks) in Tasmania, the Amritsar massacre, Balfour's perfidy in Palestine, "offering land belonging to one people as a gift to another", the great Bengal famine, the now notorious Kenyan prison camps, and British imperial arrogance and racism generally. Few of the leading "builders" of the British empire – heroes to a previous generation of imperialists – escape Paxman's scorn. The early ones were mostly pirates and freebooters. Clive of India was mainly a fortune-seeker, "scheming, and devious in business". General Gordon was "half-cracked". Cecil Rhodes was "the most sabre-toothed of all empire-builders". Kitchener was a monster. Lawrence of Arabia was romantic, but (again) "half-cracked". Churchill may not have been "quite sane" when it came to India. Lord Meath, the creator of Empire Day, is described as looking "a bit like Father Christmas", with "a bald head, a red face and an enormous white beard"; he had some silly ideas about instilling "duty and discipline" into working-class ne'er-do-wells. (David Cameron might like to look him up.) Others were mostly hypocrites, or "self-deluders" at best. The last includes Gladstone and "more recent moralists in Downing Street".

On the other hand, the book also describes atrocities committed by the colonised in, if anything, even more gory terms: the "Black Hole of Calcutta", for example, "a horror story to rival anything among the Gothic tales which swept Britain" at the time. Paxman isn't too keen on the Mahdi, Gordon's nemesis, either, with his "usual jihadi stuff" and the regime of "slavery, institutionalised paedophilia, hand-loppings and floggings to death" instituted under him. So there's a certain balance here.

More importantly, there was "another side to colonialism". Britain's most admirable imperial agents were her ordinary administrators, who Paxman thinks have been unfairly ridiculed; they were generally good eggs, and – crucially – incorruptible. The British empire was also prone to periodic spasms of moral self-questioning, which is unusual for empires, one of which in the end got rid of slavery. The postwar transition to self-government was managed "peacefully" in the main, though "in a handful of places the British fought nasty little campaigns". (I'm not sure that many Kenyans, Malayans and Cypriots would accept that "little".) Overall, "if you had to live under a foreign government," then the British empire "was better than many of the other possibilities". That "if you had to", however, is a crucial caveat.

If you have to have a popular introduction to British imperial history, too, this book could be said to be better than many of the other possibilities, in particular it is far preferable to Michael Gove's "patriotic" approach. It's a very engaging account, built mainly around dramatic incidents in exotic places (just right for the forthcoming TV series), and the lives of fascinating people, with a good sprinkling of jokes, funny nicknames and sexual references. Paxman makes some very sharp points, and writes well. Here's an example, towards the end: "The British empire had begun with a series of pounces. Then it marched. Next it swaggered. Finally, after wandering aimlessly for a while, it slunk away." If you want the appearance of the whole process described in a few short sentences, I can't imagine it done better.

He doesn't, however, delve much beneath appearances. There's nothing here on the economic, cultural or any other roots of British imperialism. Paxman is insistent that there was no great plan behind it, and that often governments were simply bumped into taking countries without really wanting to. At times he appears to be going along with what he takes to be the 19th-century historian JR Seeley's view, that the empire was accumulated "absent-mindedly". (In fact Seeley said the opposite. Everyone gets this wrong.) To his credit, Paxman repeatedly confesses his own puzzlement: "there was something inherently nonsensical about it … How could the ultimate purpose of colonisation be freedom?" Well, there is an answer to that. He might not agree with it, but he should try to understand it. Dismissing things as "nonsense" is a way of avoiding the bother of explaining them.

In view of the book's subtitle, it's a shame he doesn't say more about what the empire did to the British. He claims it "convinced the British that they were somehow special", but is very woolly about whom he means by "the British" in this context. Later on he claims that it was "mainly a ruling-class thing", with attempts to foist it on "the people" largely unsuccessful. "The noisier the loudspeakers of officialdom, the more reverberant the empty echo." This is hotly disputed in some historical circles, even for the inter-war period, which Paxman is referring to here. If it's true, however, it goes some way to explain the situation which he alleges – and deplores – at the beginning and end of his book: of widespread public amnesia about the old empire, while our prime minister pompously lectures the "lesser breeds" as if he were still wearing those baggy shorts. Hopefully he'll be watching the TV series, too.

Bernard Porter's The Lion's Share: A Short History of British Imperialism is published by Longman.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The British Empire

Re: The British Empire

Let's end the myths of Britain's imperial past

David Cameron would have us look back to the days of the British empire with pride. But there is little in the brutal oppression and naked greed with which it was built that deserves our respect

Richard Gott

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 19 October 2011 20.30 BST

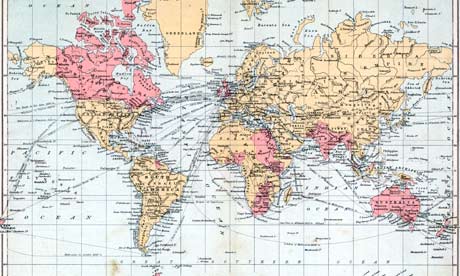

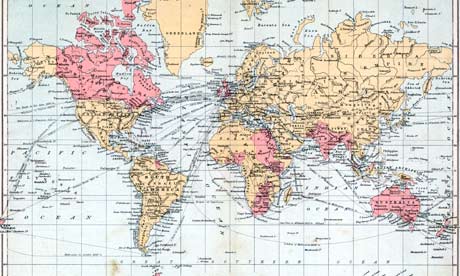

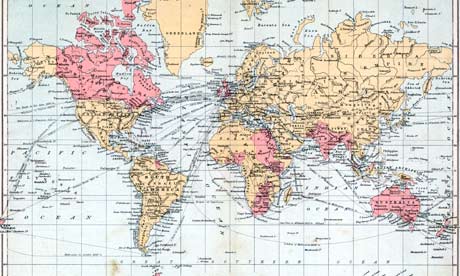

A map of c 1900 showing the possessions of the British empire in red. Photograph: Time & Life Pictures

In his speech to the Conservative party conference this month, David Cameron looked back with Tory nostalgia to the days of empire: "Britannia didn't rule the waves with armbands on," he pointed out, suggesting that the shadow of health and safety did not hover over Britain's imperial operations when the British were building "a great nation". He urged the nation to revive the spirit that had once allowed Britain to find a new role after the empire's collapse.

Britain's Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt

by Richard Gott

Tony Blair had a similar vision. "I value and honour our history enormously," he said in a speech in 1997, but he thought that Britain's empire should be the cause of "neither apology nor hand-wringing"; it should be used to further the country's global influence. And when Britain and France, two old imperial powers that had occupied Libya after 1943, began bombing that country earlier this year, there was much talk in the Middle East of the revival of European imperialism.

Half a century after the end of empire, politicians of all persuasions still feel called upon to remember our imperial past with respect. Yet few pause to notice that the descendants of the empire-builders and of their formerly subject peoples now share the small island whose inhabitants once sailed away to change the face of the world. Considerations of empire today must take account of two imperial traditions: that of the conquered as well as the conquerors. Traditionally, that first tradition has been conspicuous by its absence.

Cameron was right about the armbands. The creation of the British empire caused large portions of the global map to be tinted a rich vermilion, and the colour turned out to be peculiarly appropriate. Britain's empire was established, and maintained for more than two centuries, through bloodshed, violence, brutality, conquest and war. Not a year went by without large numbers of its inhabitants being obliged to suffer for their involuntary participation in the colonial experience. Slavery, famine, prison, battle, murder, extermination – these were their various fates.

Yet the subject peoples of empire did not go quietly into history's goodnight. Underneath the veneer of the official record exists a rather different story. Year in, year out, there was resistance to conquest, and rebellion against occupation, often followed by mutiny and revolt – by individuals, groups, armies and entire peoples. At one time or another, the British seizure of distant lands was hindered, halted and even derailed by the vehemence of local opposition.

A high price was paid by the British involved. Settlers, soldiers, convicts – those people who freshly populated the empire – were often recruited to the imperial cause as a result of the failures of government in the British Isles. These involuntary participants bore the brunt of conquest in faraway continents – death by drowning in ships that never arrived, death at the hands of indigenous peoples who refused to submit, death in foreign battles for which they bore no responsibility, death by cholera and yellow fever, the two great plagues of empire.

Many of these settlers and colonists had been forced out of Scotland, while some had been driven from Ireland, escaping from centuries of continuing oppression and periodic famine. Convicts and political prisoners were sent off to far-off gulags for minor infringements of draconian laws. Soldiers and sailors were press-ganged from the ranks of the unemployed.

Then tragically, and almost overnight, many of the formerly oppressed became themselves, in the colonies, the imperial oppressors. White settlers, in the Americas, in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, Rhodesia and Kenya, simply took over land that was not theirs, often slaughtering, and even purposefully exterminating, the local indigenous population as if they were vermin.

The empire was not established, as some of the old histories liked to suggest, in virgin territory. Far from it. In some places that the British seized, they encountered resistance from local people who had lived there for centuries or, in some cases, since time began. In other regions, notably at the end of the 18th century, lands were wrenched out of the hands of other competing colonial powers that had already begun their self-imposed task of settlement. The British, as a result, were often involved in a three-sided contest. Battles for imperial survival had to be fought both with the native inhabitants and with already existing settlers – usually of French or Dutch origin.

None of this has been, during the 60-year post-colonial period since 1947, the generally accepted view of the empire in Britain. The British understandably try to forget that their empire was the fruit of military conquest and of brutal wars involving physical and cultural extermination.

A self-satisfied and largely hegemonic belief survives in Britain that the empire was an imaginative, civilising enterprise, reluctantly undertaken, that brought the benefits of modern society to backward peoples. Indeed it is often suggested that the British empire was something of a model experience, unlike that of the French, the Dutch, the Germans, the Spaniards, the Portuguese – or, of course, the Americans. There is a widespread opinion that the British empire was obtained and maintained with a minimum degree of force and with maximum co-operation from a grateful local population.

This benign, biscuit-tin view of the past is not an understanding of their history that young people in the territories that once made up the empire would now recognise. A myriad revisionist historians have been at work in each individual country producing fresh evidence to suggest that the colonial experience – for those who actually "experienced" it – was just as horrific as the opponents of empire had always maintained that it was, perhaps more so. New generations have been recovering tales of rebellion, repression and resistance that make nonsense of the accepted imperial version of what went on. Focusing on resistance has been a way of challenging not just the traditional, self-satisfied view of empire, but also the customary depiction of the colonised as victims, lacking in agency or political will.

The theme of repression has often been underplayed in traditional accounts. A few particular instances are customarily highlighted – the slaughter after the Indian mutiny in 1857, the massacre at Amritsar in 1919, the crushing of the Jamaican rebellion in 1867. These have been unavoidable tales. Yet the sheer scale and continuity of imperial repression over the years has never been properly laid out and documented.

No colony in their empire gave the British more trouble than the island of Ireland. No subject people proved more rebellious than the Irish. From misty start to unending finish, Irish revolt against colonial rule has been the leitmotif that runs through the entire history of empire, causing problems in Ireland, in England itself, and in the most distant parts of the British globe. The British affected to ignore or forget the Irish dimension to their empire, yet the Irish were always present within it, and wherever they landed and established themselves, they never forgot where they had come from.

The British often perceived the Irish as "savages", and they used Ireland as an experimental laboratory for the other parts of their overseas empire, as a place to ship out settlers from, as well as a territory to practise techniques of repression and control. Entire armies were recruited in Ireland, and officers learned their trade in its peat bogs and among its burning cottages. Some of the great names of British military history – from Wellington and Wolseley to Kitchener and Montgomery – were indelibly associated with Ireland. The particular tradition of armed policing, first patented in Ireland in the 1820s, became the established pattern until the empire's final collapse.

For much of its early history, the British ruled their empire through terror. The colonies were run as a military dictatorship, often under martial law, and the majority of colonial governors were military officers. "Special" courts and courts martial were set up to deal with dissidents, and handed out rough and speedy injustice. Normal judicial procedures were replaced by rule through terror; resistance was crushed, rebellion suffocated. No historical or legal work deals with martial law. It means the absence of law, other than that decreed by a military governor.

Many early campaigns in India in the 18th century were characterised by sepoy disaffection. Britain's harsh treatment of sepoy mutineers at Manjee in 1764, with the order that they should be "shot from guns", was a terrible warning to others not to step out of line. Mutiny, as the British discovered a century later in 1857, was a formidable weapon of resistance at the disposal of the soldiers they had trained. Crushing it through "cannonading", standing the condemned prisoner with his shoulders placed against the muzzle of a cannon, was essential to the maintenance of imperial control. This simple threat helped to keep the sepoys in line throughout most of imperial history.

To defend its empire, to construct its rudimentary systems of communication and transport, and to man its plantation economies, the British used forced labour on a gigantic scale. From the middle of the 18th century until 1834, the use of non-indigenous black slave labour originally shipped from Africa was the rule. Indigenous manpower in many imperial states was also subjected to slave conditions, dragooned into the imperial armies, or forcibly recruited into road gangs – building the primitive communication networks that facilitated the speedy repression of rebellion. When black slavery was abolished in the 1830s, the thirst for labour by the rapacious landowners of empire brought a new type of slavery into existence, dragging workers from India and China to be employed in distant parts of the world, a phenomenon that soon brought its own contradictions and conflicts.

As with other great imperial constructs, the British empire involved vast movements of peoples: armies were switched from one part of the world to another; settlers changed continents and hemispheres; prisoners were sent from country to country; indigenous inhabitants were corralled, driven away into oblivion, or simply rubbed out.

There was nothing historically special about the British empire. Virtually all European countries with sea coasts and navies had embarked on programmes of expansion in the 16th century, trading, fighting and settling in distant parts of the globe. Sometimes, having made some corner of the map their own, they would exchange it for another piece "owned" by another power, and often these exchanges would occur as the byproduct of dynastic marriages. The Spanish and the Portuguese and the Dutch had empires; so too did the French and the Italians, and the Germans and the Belgians. World empire, in the sense of a far-flung operation far from home, was a European development that changed the world over four centuries.

In the British case, wherever they sought to plant their flag, they were met with opposition. In almost every colony they had to fight their way ashore. While they could sometimes count on a handful of friends and allies, they never arrived as welcome guests. The expansion of empire was conducted as a military operation. The initial opposition continued off and on, and in varying forms, in almost every colonial territory until independence. To retain control, the British were obliged to establish systems of oppression on a global scale, ranging from the sophisticated to the brutal. These in turn were to create new outbreaks of revolt.

Over two centuries, this resistance took many forms and had many leaders. Sometimes kings and nobles led the revolts, sometimes priests or slaves. Some have famous names and biographies, others have disappeared almost without trace. Many died violent deaths. Few of them have even a walk-on part in traditional accounts of empire. Many of these forgotten peoples deserve to be resurrected and given the attention they deserve.

The rebellions and resistance of the subject peoples of empire were so extensive that we may eventually come to consider that Britain's imperial experience bears comparison with the exploits of Genghis Khan or Attila the Hun rather than with those of Alexander the Great. The rulers of the empire may one day be perceived to rank with the dictators of the 20th century as the authors of crimes against humanity.

The drive towards the annihilation of dissidents and peoples in 20th-century Europe certainly had precedents in the 19th-century imperial operations in the colonial world, where the elimination of "inferior" peoples was seen by some to be historically inevitable, and where the experience helped in the construction of the racist ideologies that arose subsequently in Europe. Later technologies merely enlarged the scale of what had gone before. As Cameron remarked this month, Britannia did not rule the waves with armbands on.

Richard Gott's new book, Britain's Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt, is published by Verso (£25).

© 2011 Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. All rights reserved.

David Cameron would have us look back to the days of the British empire with pride. But there is little in the brutal oppression and naked greed with which it was built that deserves our respect

Richard Gott

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 19 October 2011 20.30 BST

A map of c 1900 showing the possessions of the British empire in red. Photograph: Time & Life Pictures

In his speech to the Conservative party conference this month, David Cameron looked back with Tory nostalgia to the days of empire: "Britannia didn't rule the waves with armbands on," he pointed out, suggesting that the shadow of health and safety did not hover over Britain's imperial operations when the British were building "a great nation". He urged the nation to revive the spirit that had once allowed Britain to find a new role after the empire's collapse.

Britain's Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt

by Richard Gott

Tony Blair had a similar vision. "I value and honour our history enormously," he said in a speech in 1997, but he thought that Britain's empire should be the cause of "neither apology nor hand-wringing"; it should be used to further the country's global influence. And when Britain and France, two old imperial powers that had occupied Libya after 1943, began bombing that country earlier this year, there was much talk in the Middle East of the revival of European imperialism.

Half a century after the end of empire, politicians of all persuasions still feel called upon to remember our imperial past with respect. Yet few pause to notice that the descendants of the empire-builders and of their formerly subject peoples now share the small island whose inhabitants once sailed away to change the face of the world. Considerations of empire today must take account of two imperial traditions: that of the conquered as well as the conquerors. Traditionally, that first tradition has been conspicuous by its absence.

Cameron was right about the armbands. The creation of the British empire caused large portions of the global map to be tinted a rich vermilion, and the colour turned out to be peculiarly appropriate. Britain's empire was established, and maintained for more than two centuries, through bloodshed, violence, brutality, conquest and war. Not a year went by without large numbers of its inhabitants being obliged to suffer for their involuntary participation in the colonial experience. Slavery, famine, prison, battle, murder, extermination – these were their various fates.

Yet the subject peoples of empire did not go quietly into history's goodnight. Underneath the veneer of the official record exists a rather different story. Year in, year out, there was resistance to conquest, and rebellion against occupation, often followed by mutiny and revolt – by individuals, groups, armies and entire peoples. At one time or another, the British seizure of distant lands was hindered, halted and even derailed by the vehemence of local opposition.

A high price was paid by the British involved. Settlers, soldiers, convicts – those people who freshly populated the empire – were often recruited to the imperial cause as a result of the failures of government in the British Isles. These involuntary participants bore the brunt of conquest in faraway continents – death by drowning in ships that never arrived, death at the hands of indigenous peoples who refused to submit, death in foreign battles for which they bore no responsibility, death by cholera and yellow fever, the two great plagues of empire.

Many of these settlers and colonists had been forced out of Scotland, while some had been driven from Ireland, escaping from centuries of continuing oppression and periodic famine. Convicts and political prisoners were sent off to far-off gulags for minor infringements of draconian laws. Soldiers and sailors were press-ganged from the ranks of the unemployed.

Then tragically, and almost overnight, many of the formerly oppressed became themselves, in the colonies, the imperial oppressors. White settlers, in the Americas, in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, Rhodesia and Kenya, simply took over land that was not theirs, often slaughtering, and even purposefully exterminating, the local indigenous population as if they were vermin.

The empire was not established, as some of the old histories liked to suggest, in virgin territory. Far from it. In some places that the British seized, they encountered resistance from local people who had lived there for centuries or, in some cases, since time began. In other regions, notably at the end of the 18th century, lands were wrenched out of the hands of other competing colonial powers that had already begun their self-imposed task of settlement. The British, as a result, were often involved in a three-sided contest. Battles for imperial survival had to be fought both with the native inhabitants and with already existing settlers – usually of French or Dutch origin.

None of this has been, during the 60-year post-colonial period since 1947, the generally accepted view of the empire in Britain. The British understandably try to forget that their empire was the fruit of military conquest and of brutal wars involving physical and cultural extermination.

A self-satisfied and largely hegemonic belief survives in Britain that the empire was an imaginative, civilising enterprise, reluctantly undertaken, that brought the benefits of modern society to backward peoples. Indeed it is often suggested that the British empire was something of a model experience, unlike that of the French, the Dutch, the Germans, the Spaniards, the Portuguese – or, of course, the Americans. There is a widespread opinion that the British empire was obtained and maintained with a minimum degree of force and with maximum co-operation from a grateful local population.

This benign, biscuit-tin view of the past is not an understanding of their history that young people in the territories that once made up the empire would now recognise. A myriad revisionist historians have been at work in each individual country producing fresh evidence to suggest that the colonial experience – for those who actually "experienced" it – was just as horrific as the opponents of empire had always maintained that it was, perhaps more so. New generations have been recovering tales of rebellion, repression and resistance that make nonsense of the accepted imperial version of what went on. Focusing on resistance has been a way of challenging not just the traditional, self-satisfied view of empire, but also the customary depiction of the colonised as victims, lacking in agency or political will.

The theme of repression has often been underplayed in traditional accounts. A few particular instances are customarily highlighted – the slaughter after the Indian mutiny in 1857, the massacre at Amritsar in 1919, the crushing of the Jamaican rebellion in 1867. These have been unavoidable tales. Yet the sheer scale and continuity of imperial repression over the years has never been properly laid out and documented.

No colony in their empire gave the British more trouble than the island of Ireland. No subject people proved more rebellious than the Irish. From misty start to unending finish, Irish revolt against colonial rule has been the leitmotif that runs through the entire history of empire, causing problems in Ireland, in England itself, and in the most distant parts of the British globe. The British affected to ignore or forget the Irish dimension to their empire, yet the Irish were always present within it, and wherever they landed and established themselves, they never forgot where they had come from.

The British often perceived the Irish as "savages", and they used Ireland as an experimental laboratory for the other parts of their overseas empire, as a place to ship out settlers from, as well as a territory to practise techniques of repression and control. Entire armies were recruited in Ireland, and officers learned their trade in its peat bogs and among its burning cottages. Some of the great names of British military history – from Wellington and Wolseley to Kitchener and Montgomery – were indelibly associated with Ireland. The particular tradition of armed policing, first patented in Ireland in the 1820s, became the established pattern until the empire's final collapse.

For much of its early history, the British ruled their empire through terror. The colonies were run as a military dictatorship, often under martial law, and the majority of colonial governors were military officers. "Special" courts and courts martial were set up to deal with dissidents, and handed out rough and speedy injustice. Normal judicial procedures were replaced by rule through terror; resistance was crushed, rebellion suffocated. No historical or legal work deals with martial law. It means the absence of law, other than that decreed by a military governor.

Many early campaigns in India in the 18th century were characterised by sepoy disaffection. Britain's harsh treatment of sepoy mutineers at Manjee in 1764, with the order that they should be "shot from guns", was a terrible warning to others not to step out of line. Mutiny, as the British discovered a century later in 1857, was a formidable weapon of resistance at the disposal of the soldiers they had trained. Crushing it through "cannonading", standing the condemned prisoner with his shoulders placed against the muzzle of a cannon, was essential to the maintenance of imperial control. This simple threat helped to keep the sepoys in line throughout most of imperial history.

To defend its empire, to construct its rudimentary systems of communication and transport, and to man its plantation economies, the British used forced labour on a gigantic scale. From the middle of the 18th century until 1834, the use of non-indigenous black slave labour originally shipped from Africa was the rule. Indigenous manpower in many imperial states was also subjected to slave conditions, dragooned into the imperial armies, or forcibly recruited into road gangs – building the primitive communication networks that facilitated the speedy repression of rebellion. When black slavery was abolished in the 1830s, the thirst for labour by the rapacious landowners of empire brought a new type of slavery into existence, dragging workers from India and China to be employed in distant parts of the world, a phenomenon that soon brought its own contradictions and conflicts.

As with other great imperial constructs, the British empire involved vast movements of peoples: armies were switched from one part of the world to another; settlers changed continents and hemispheres; prisoners were sent from country to country; indigenous inhabitants were corralled, driven away into oblivion, or simply rubbed out.

There was nothing historically special about the British empire. Virtually all European countries with sea coasts and navies had embarked on programmes of expansion in the 16th century, trading, fighting and settling in distant parts of the globe. Sometimes, having made some corner of the map their own, they would exchange it for another piece "owned" by another power, and often these exchanges would occur as the byproduct of dynastic marriages. The Spanish and the Portuguese and the Dutch had empires; so too did the French and the Italians, and the Germans and the Belgians. World empire, in the sense of a far-flung operation far from home, was a European development that changed the world over four centuries.

In the British case, wherever they sought to plant their flag, they were met with opposition. In almost every colony they had to fight their way ashore. While they could sometimes count on a handful of friends and allies, they never arrived as welcome guests. The expansion of empire was conducted as a military operation. The initial opposition continued off and on, and in varying forms, in almost every colonial territory until independence. To retain control, the British were obliged to establish systems of oppression on a global scale, ranging from the sophisticated to the brutal. These in turn were to create new outbreaks of revolt.

Over two centuries, this resistance took many forms and had many leaders. Sometimes kings and nobles led the revolts, sometimes priests or slaves. Some have famous names and biographies, others have disappeared almost without trace. Many died violent deaths. Few of them have even a walk-on part in traditional accounts of empire. Many of these forgotten peoples deserve to be resurrected and given the attention they deserve.

The rebellions and resistance of the subject peoples of empire were so extensive that we may eventually come to consider that Britain's imperial experience bears comparison with the exploits of Genghis Khan or Attila the Hun rather than with those of Alexander the Great. The rulers of the empire may one day be perceived to rank with the dictators of the 20th century as the authors of crimes against humanity.

The drive towards the annihilation of dissidents and peoples in 20th-century Europe certainly had precedents in the 19th-century imperial operations in the colonial world, where the elimination of "inferior" peoples was seen by some to be historically inevitable, and where the experience helped in the construction of the racist ideologies that arose subsequently in Europe. Later technologies merely enlarged the scale of what had gone before. As Cameron remarked this month, Britannia did not rule the waves with armbands on.

Richard Gott's new book, Britain's Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt, is published by Verso (£25).

© 2011 Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. All rights reserved.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The British Empire

Re: The British Empire

eddie wrote:Over two centuries, this resistance took many forms and had many leaders. Sometimes kings and nobles led the revolts, sometimes priests or slaves. Some have famous names and biographies, others have disappeared almost without trace. Many died violent deaths. Few of them have even a walk-on part in traditional accounts of empire. Many of these forgotten peoples deserve to be resurrected and given the attention they deserve.

edit: you'll like this one eddie. It's where they send a shaman to catch a shaman and they battle to the death

...Jandamarra (Pigeon): 1890s outlaw

Bunuba tribe

Kimberley region (the remote north of Wesrern Australia)

European settlers opening up huge tracts of the Kimberley for grazing cattle

Aboriginal people driven from their lands or forced to work on the cattle stations.

Forbidden to hunt on their land, when caught spearing sheep or cattle they were forced to work in neck chains.

Away from their home land.

Pigeon belonged to the Bunuba tribe and had contact with European settlers. He worked on stations (jailed for spearing cattle once)

An excellent horseman and marksman.

Because of his jail term, he was not fully trained in his own tribal law.

The jail time had interrupted that education.

He broke the strict kinship rules of the Bunuba by having sexual relations with prohibited women and was banished from his tribal society.

Left out alone he turned to the Europeans, became friends with Police Constable Richardson and started working as a tracker for the police.

On one of their patrols in the Napier Range Richardson and Jandamarra captured a large group of Bunuba, Jandamarra's kinsmen and women. The group was held at Lillimura Police Post for a few days. And even though he had helped capturing the group, Jandamarra was now overcome by remorse as his tribal roots got the better of him.

And Pigeon shot Richardson, set the group free, stole some weapons and disappeared.

From then on he used the ranges and caves of Windjana Gorge and Tunnel Creek as hideouts as he led an organised armed rebellion against the European settlers.

November 10, 1894 marks the first organised attack that used guns against Europeans. Pigeon and his men ambushed a group of of five settlers who were driving cattle into Bunuba land to set up a large station. Two of the settlers, Burke and Gibbs, were killed at Windjana Gorge.

In late 1894 Europeans thought they had won a victory. A group of thirty police and settlers attacked Jandamarra and his band at Windjana Gorge. Jandamarra was seriously wounded and thought dead.

Then the police continued their operation, raiding the Aboriginal camps in the Fitzroy Crossing area and killing many, even though none of those Aboriginals were known to have anything to do with Jandamarra...

But Jandamarra sure wasn't dead yet. He recovered and for the next three years defended his land and people against the white intruders. His ability to appear out of nowhere and disappear without a trace became legend.

Once a police patrol followed him to his Tunnel Creek hideout (The "Cave of Bats"). Or so they thought. While they were at Tunnel Creek, Jandamarra was actually raiding THEIR base, the Lillimura Police Post.

Aboriginal people were in awe of Pigeon, a man of magical powers who could "fly like a bird and disappear like a ghost". They were convinced that he was immortal, that the only person who could kill him would have to be an Aboriginal person with similar magical powers.

It seems Micki was that person...

Micki was a black tracker whom the police had recruited in the Pilbara. And he WAS said to possess magical powers as well, and he did not fear Pigeon.

With the help of Micki the police managed to track down Jandamarra at Tunnel Creek on April 1, 1897. Jandamarra was killed in the shoot out, and another battle for Aboriginal lands came to an end. condensed and paraphrased from http://www.kimberleyaustralia.com/story-of-jandamarra.html

Last edited by blue moon on Thu Oct 20, 2011 10:18 pm; edited 2 times in total

Guest- Guest

Re: The British Empire

Re: The British Empire

edit: the above picture isn't of pigeon or micki, but it is concurrent with them.

Guest- Guest

Re: The British Empire

Re: The British Empire

[quote="eddie"]Let's end the myths of Britain's imperial past

David Cameron would have us look back to the days of the British empire with pride. But there is little in the brutal oppression and naked greed with which it was built that deserves our respect

Richard Gott

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 19 October 2011 20.30 BST

A map of c 1900 showing the possessions of the British empire in red. Photograph: Time & Life Pictures

In his speech to the Conservative party conference this month, David Cameron looked back with Tory nostalgia to the days of empire: "Britannia didn't rule the waves with armbands on," he pointed out, suggesting that the shadow of health and safety did not hover over Britain's imperial operations when the British were building "a great nation". He urged the nation to revive the spirit that had once allowed Britain to find a new role after the empire's collapse.

Britain's Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt

by Richard Gott

Tony Blair had a similar vision. "I value and honour our history enormously," he said in a speech in 1997, but he thought that Britain's empire should be the cause of "neither apology nor hand-wringing"; it should be used to further the country's global influence. And when Britain and France, two old imperial powers that had occupied Libya after 1943, began bombing that country earlier this year, there was much talk in the Middle East of the revival of European imperialism.

Half a century after the end of empire, politicians of all persuasions still feel called upon to remember our imperial past with respect. Yet few pause to notice that the descendants of the empire-builders and of their formerly subject peoples now share the small island whose inhabitants once sailed away to change the face of the world. Considerations of empire today must take account of two imperial traditions: that of the conquered as well as the conquerors. Traditionally, that first tradition has been conspicuous by its absence.

Cameron was right about the armbands. The creation of the British empire caused large portions of the global map to be tinted a rich vermilion, and the colour turned out to be peculiarly appropriate. Britain's empire was established, and maintained for more than two centuries, through bloodshed, violence, brutality, conquest and war. Not a year went by without large numbers of its inhabitants being obliged to suffer for their involuntary participation in the colonial experience. Slavery, famine, prison, battle, murder, extermination – these were their various fates.

Yet the subject peoples of empire did not go quietly into history's goodnight. Underneath the veneer of the official record exists a rather different story. Year in, year out, there was resistance to conquest, and rebellion against occupation, often followed by mutiny and revolt – by individuals, groups, armies and entire peoples. At one time or another, the British seizure of distant lands was hindered, halted and even derailed by the vehemence of local opposition.

A high price was paid by the British involved. Settlers, soldiers, convicts – those people who freshly populated the empire – were often recruited to the imperial cause as a result of the failures of government in the British Isles. These involuntary participants bore the brunt of conquest in faraway continents – death by drowning in ships that never arrived, death at the hands of indigenous peoples who refused to submit, death in foreign battles for which they bore no responsibility, death by cholera and yellow fever, the two great plagues of empire.

Many of these settlers and colonists had been forced out of Scotland, while some had been driven from Ireland, escaping from centuries of continuing oppression and periodic famine. Convicts and political prisoners were sent off to far-off gulags for minor infringements of draconian laws. Soldiers and sailors were press-ganged from the ranks of the unemployed.

Then tragically, and almost overnight, many of the formerly oppressed became themselves, in the colonies, the imperial oppressors. White settlers, in the Americas, in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, Rhodesia and Kenya, simply took over land that was not theirs, often slaughtering, and even purposefully exterminating, the local indigenous population as if they were vermin.

The empire was not established, as some of the old histories liked to suggest, in virgin territory. Far from it. In some places that the British seized, they encountered resistance from local people who had lived there for centuries or, in some cases, since time began. In other regions, notably at the end of the 18th century, lands were wrenched out of the hands of other competing colonial powers that had already begun their self-imposed task of settlement. The British, as a result, were often involved in a three-sided contest. Battles for imperial survival had to be fought both with the native inhabitants and with already existing settlers – usually of French or Dutch origin.

None of this has been, during the 60-year post-colonial period since 1947, the generally accepted view of the empire in Britain. The British understandably try to forget that their empire was the fruit of military conquest and of brutal wars involving physical and cultural extermination.

A self-satisfied and largely hegemonic belief survives in Britain that the empire was an imaginative, civilising enterprise, reluctantly undertaken, that brought the benefits of modern society to backward peoples. Indeed it is often suggested that the British empire was something of a model experience, unlike that of the French, the Dutch, the Germans, the Spaniards, the Portuguese – or, of course, the Americans. There is a widespread opinion that the British empire was obtained and maintained with a minimum degree of force and with maximum co-operation from a grateful local population.

This benign, biscuit-tin view of the past is not an understanding of their history that young people in the territories that once made up the empire would now recognise. A myriad revisionist historians have been at work in each individual country producing fresh evidence to suggest that the colonial experience – for those who actually "experienced" it – was just as horrific as the opponents of empire had always maintained that it was, perhaps more so. New generations have been recovering tales of rebellion, repression and resistance that make nonsense of the accepted imperial version of what went on. Focusing on resistance has been a way of challenging not just the traditional, self-satisfied view of empire, but also the customary depiction of the colonised as victims, lacking in agency or political will.

The theme of repression has often been underplayed in traditional accounts. A few particular instances are customarily highlighted – the slaughter after the Indian mutiny in 1857, the massacre at Amritsar in 1919, the crushing of the Jamaican rebellion in 1867. These have been unavoidable tales. Yet the sheer scale and continuity of imperial repression over the years has never been properly laid out and documented.

No colony in their empire gave the British more trouble than the island of Ireland. No subject people proved more rebellious than the Irish. From misty start to unending finish, Irish revolt against colonial rule has been the leitmotif that runs through the entire history of empire, causing problems in Ireland, in England itself, and in the most distant parts of the British globe. The British affected to ignore or forget the Irish dimension to their empire, yet the Irish were always present within it, and wherever they landed and established themselves, they never forgot where they had come from.

The British often perceived the Irish as "savages", and they used Ireland as an experimental laboratory for the other parts of their overseas empire, as a place to ship out settlers from, as well as a territory to practise techniques of repression and control. Entire armies were recruited in Ireland, and officers learned their trade in its peat bogs and among its burning cottages. Some of the great names of British military history – from Wellington and Wolseley to Kitchener and Montgomery – were indelibly associated with Ireland. The particular tradition of armed policing, first patented in Ireland in the 1820s, became the established pattern until the empire's final collapse.

For much of its early history, the British ruled their empire through terror. The colonies were run as a military dictatorship, often under martial law, and the majority of colonial governors were military officers. "Special" courts and courts martial were set up to deal with dissidents, and handed out rough and speedy injustice. Normal judicial procedures were replaced by rule through terror; resistance was crushed, rebellion suffocated. No historical or legal work deals with martial law. It means the absence of law, other than that decreed by a military governor.

Many early campaigns in India in the 18th century were characterised by sepoy disaffection. Britain's harsh treatment of sepoy mutineers at Manjee in 1764, with the order that they should be "shot from guns", was a terrible warning to others not to step out of line. Mutiny, as the British discovered a century later in 1857, was a formidable weapon of resistance at the disposal of the soldiers they had trained. Crushing it through "cannonading", standing the condemned prisoner with his shoulders placed against the muzzle of a cannon, was essential to the maintenance of imperial control. This simple threat helped to keep the sepoys in line throughout most of imperial history.

To defend its empire, to construct its rudimentary systems of communication and transport, and to man its plantation economies, the British used forced labour on a gigantic scale. From the middle of the 18th century until 1834, the use of non-indigenous black slave labour originally shipped from Africa was the rule. Indigenous manpower in many imperial states was also subjected to slave conditions, dragooned into the imperial armies, or forcibly recruited into road gangs – building the primitive communication networks that facilitated the speedy repression of rebellion. When black slavery was abolished in the 1830s, the thirst for labour by the rapacious landowners of empire brought a new type of slavery into existence, dragging workers from India and China to be employed in distant parts of the world, a phenomenon that soon brought its own contradictions and conflicts.

As with other great imperial constructs, the British empire involved vast movements of peoples: armies were switched from one part of the world to another; settlers changed continents and hemispheres; prisoners were sent from country to country; indigenous inhabitants were corralled, driven away into oblivion, or simply rubbed out.

There was nothing historically special about the British empire. Virtually all European countries with sea coasts and navies had embarked on programmes of expansion in the 16th century, trading, fighting and settling in distant parts of the globe. Sometimes, having made some corner of the map their own, they would exchange it for another piece "owned" by another power, and often these exchanges would occur as the byproduct of dynastic marriages. The Spanish and the Portuguese and the Dutch had empires; so too did the French and the Italians, and the Germans and the Belgians. World empire, in the sense of a far-flung operation far from home, was a European development that changed the world over four centuries.

In the British case, wherever they sought to plant their flag, they were met with opposition. In almost every colony they had to fight their way ashore. While they could sometimes count on a handful of friends and allies, they never arrived as welcome guests. The expansion of empire was conducted as a military operation. The initial opposition continued off and on, and in varying forms, in almost every colonial territory until independence. To retain control, the British were obliged to establish systems of oppression on a global scale, ranging from the sophisticated to the brutal. These in turn were to create new outbreaks of revolt.

Over two centuries, this resistance took many forms and had many leaders. Sometimes kings and nobles led the revolts, sometimes priests or slaves. Some have famous names and biographies, others have disappeared almost without trace. Many died violent deaths. Few of them have even a walk-on part in traditional accounts of empire. Many of these forgotten peoples deserve to be resurrected and given the attention they deserve.

The rebellions and resistance of the subject peoples of empire were so extensive that we may eventually come to consider that Britain's imperial experience bears comparison with the exploits of Genghis Khan or Attila the Hun rather than with those of Alexander the Great. The rulers of the empire may one day be perceived to rank with the dictators of the 20th century as the authors of crimes against humanity.

The drive towards the annihilation of dissidents and peoples in 20th-century Europe certainly had precedents in the 19th-century imperial operations in the colonial world, where the elimination of "inferior" peoples was seen by some to be historically inevitable, and where the experience helped in the construction of the racist ideologies that arose subsequently in Europe. Later technologies merely enlarged the scale of what had gone before. As Cameron remarked this month, Britannia did not rule the waves with armbands on.

Richard Gott's new book, Britain's Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt, is published by Verso (£25).

© 2011 Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. All rights reserved.

[/quote

That map is simply astonishing.

David Cameron would have us look back to the days of the British empire with pride. But there is little in the brutal oppression and naked greed with which it was built that deserves our respect

Richard Gott

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 19 October 2011 20.30 BST

A map of c 1900 showing the possessions of the British empire in red. Photograph: Time & Life Pictures

In his speech to the Conservative party conference this month, David Cameron looked back with Tory nostalgia to the days of empire: "Britannia didn't rule the waves with armbands on," he pointed out, suggesting that the shadow of health and safety did not hover over Britain's imperial operations when the British were building "a great nation". He urged the nation to revive the spirit that had once allowed Britain to find a new role after the empire's collapse.

Britain's Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt

by Richard Gott

Tony Blair had a similar vision. "I value and honour our history enormously," he said in a speech in 1997, but he thought that Britain's empire should be the cause of "neither apology nor hand-wringing"; it should be used to further the country's global influence. And when Britain and France, two old imperial powers that had occupied Libya after 1943, began bombing that country earlier this year, there was much talk in the Middle East of the revival of European imperialism.

Half a century after the end of empire, politicians of all persuasions still feel called upon to remember our imperial past with respect. Yet few pause to notice that the descendants of the empire-builders and of their formerly subject peoples now share the small island whose inhabitants once sailed away to change the face of the world. Considerations of empire today must take account of two imperial traditions: that of the conquered as well as the conquerors. Traditionally, that first tradition has been conspicuous by its absence.

Cameron was right about the armbands. The creation of the British empire caused large portions of the global map to be tinted a rich vermilion, and the colour turned out to be peculiarly appropriate. Britain's empire was established, and maintained for more than two centuries, through bloodshed, violence, brutality, conquest and war. Not a year went by without large numbers of its inhabitants being obliged to suffer for their involuntary participation in the colonial experience. Slavery, famine, prison, battle, murder, extermination – these were their various fates.

Yet the subject peoples of empire did not go quietly into history's goodnight. Underneath the veneer of the official record exists a rather different story. Year in, year out, there was resistance to conquest, and rebellion against occupation, often followed by mutiny and revolt – by individuals, groups, armies and entire peoples. At one time or another, the British seizure of distant lands was hindered, halted and even derailed by the vehemence of local opposition.

A high price was paid by the British involved. Settlers, soldiers, convicts – those people who freshly populated the empire – were often recruited to the imperial cause as a result of the failures of government in the British Isles. These involuntary participants bore the brunt of conquest in faraway continents – death by drowning in ships that never arrived, death at the hands of indigenous peoples who refused to submit, death in foreign battles for which they bore no responsibility, death by cholera and yellow fever, the two great plagues of empire.

Many of these settlers and colonists had been forced out of Scotland, while some had been driven from Ireland, escaping from centuries of continuing oppression and periodic famine. Convicts and political prisoners were sent off to far-off gulags for minor infringements of draconian laws. Soldiers and sailors were press-ganged from the ranks of the unemployed.

Then tragically, and almost overnight, many of the formerly oppressed became themselves, in the colonies, the imperial oppressors. White settlers, in the Americas, in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada, Rhodesia and Kenya, simply took over land that was not theirs, often slaughtering, and even purposefully exterminating, the local indigenous population as if they were vermin.

The empire was not established, as some of the old histories liked to suggest, in virgin territory. Far from it. In some places that the British seized, they encountered resistance from local people who had lived there for centuries or, in some cases, since time began. In other regions, notably at the end of the 18th century, lands were wrenched out of the hands of other competing colonial powers that had already begun their self-imposed task of settlement. The British, as a result, were often involved in a three-sided contest. Battles for imperial survival had to be fought both with the native inhabitants and with already existing settlers – usually of French or Dutch origin.

None of this has been, during the 60-year post-colonial period since 1947, the generally accepted view of the empire in Britain. The British understandably try to forget that their empire was the fruit of military conquest and of brutal wars involving physical and cultural extermination.

A self-satisfied and largely hegemonic belief survives in Britain that the empire was an imaginative, civilising enterprise, reluctantly undertaken, that brought the benefits of modern society to backward peoples. Indeed it is often suggested that the British empire was something of a model experience, unlike that of the French, the Dutch, the Germans, the Spaniards, the Portuguese – or, of course, the Americans. There is a widespread opinion that the British empire was obtained and maintained with a minimum degree of force and with maximum co-operation from a grateful local population.

This benign, biscuit-tin view of the past is not an understanding of their history that young people in the territories that once made up the empire would now recognise. A myriad revisionist historians have been at work in each individual country producing fresh evidence to suggest that the colonial experience – for those who actually "experienced" it – was just as horrific as the opponents of empire had always maintained that it was, perhaps more so. New generations have been recovering tales of rebellion, repression and resistance that make nonsense of the accepted imperial version of what went on. Focusing on resistance has been a way of challenging not just the traditional, self-satisfied view of empire, but also the customary depiction of the colonised as victims, lacking in agency or political will.

The theme of repression has often been underplayed in traditional accounts. A few particular instances are customarily highlighted – the slaughter after the Indian mutiny in 1857, the massacre at Amritsar in 1919, the crushing of the Jamaican rebellion in 1867. These have been unavoidable tales. Yet the sheer scale and continuity of imperial repression over the years has never been properly laid out and documented.

No colony in their empire gave the British more trouble than the island of Ireland. No subject people proved more rebellious than the Irish. From misty start to unending finish, Irish revolt against colonial rule has been the leitmotif that runs through the entire history of empire, causing problems in Ireland, in England itself, and in the most distant parts of the British globe. The British affected to ignore or forget the Irish dimension to their empire, yet the Irish were always present within it, and wherever they landed and established themselves, they never forgot where they had come from.

The British often perceived the Irish as "savages", and they used Ireland as an experimental laboratory for the other parts of their overseas empire, as a place to ship out settlers from, as well as a territory to practise techniques of repression and control. Entire armies were recruited in Ireland, and officers learned their trade in its peat bogs and among its burning cottages. Some of the great names of British military history – from Wellington and Wolseley to Kitchener and Montgomery – were indelibly associated with Ireland. The particular tradition of armed policing, first patented in Ireland in the 1820s, became the established pattern until the empire's final collapse.

For much of its early history, the British ruled their empire through terror. The colonies were run as a military dictatorship, often under martial law, and the majority of colonial governors were military officers. "Special" courts and courts martial were set up to deal with dissidents, and handed out rough and speedy injustice. Normal judicial procedures were replaced by rule through terror; resistance was crushed, rebellion suffocated. No historical or legal work deals with martial law. It means the absence of law, other than that decreed by a military governor.

Many early campaigns in India in the 18th century were characterised by sepoy disaffection. Britain's harsh treatment of sepoy mutineers at Manjee in 1764, with the order that they should be "shot from guns", was a terrible warning to others not to step out of line. Mutiny, as the British discovered a century later in 1857, was a formidable weapon of resistance at the disposal of the soldiers they had trained. Crushing it through "cannonading", standing the condemned prisoner with his shoulders placed against the muzzle of a cannon, was essential to the maintenance of imperial control. This simple threat helped to keep the sepoys in line throughout most of imperial history.

To defend its empire, to construct its rudimentary systems of communication and transport, and to man its plantation economies, the British used forced labour on a gigantic scale. From the middle of the 18th century until 1834, the use of non-indigenous black slave labour originally shipped from Africa was the rule. Indigenous manpower in many imperial states was also subjected to slave conditions, dragooned into the imperial armies, or forcibly recruited into road gangs – building the primitive communication networks that facilitated the speedy repression of rebellion. When black slavery was abolished in the 1830s, the thirst for labour by the rapacious landowners of empire brought a new type of slavery into existence, dragging workers from India and China to be employed in distant parts of the world, a phenomenon that soon brought its own contradictions and conflicts.

As with other great imperial constructs, the British empire involved vast movements of peoples: armies were switched from one part of the world to another; settlers changed continents and hemispheres; prisoners were sent from country to country; indigenous inhabitants were corralled, driven away into oblivion, or simply rubbed out.

There was nothing historically special about the British empire. Virtually all European countries with sea coasts and navies had embarked on programmes of expansion in the 16th century, trading, fighting and settling in distant parts of the globe. Sometimes, having made some corner of the map their own, they would exchange it for another piece "owned" by another power, and often these exchanges would occur as the byproduct of dynastic marriages. The Spanish and the Portuguese and the Dutch had empires; so too did the French and the Italians, and the Germans and the Belgians. World empire, in the sense of a far-flung operation far from home, was a European development that changed the world over four centuries.

In the British case, wherever they sought to plant their flag, they were met with opposition. In almost every colony they had to fight their way ashore. While they could sometimes count on a handful of friends and allies, they never arrived as welcome guests. The expansion of empire was conducted as a military operation. The initial opposition continued off and on, and in varying forms, in almost every colonial territory until independence. To retain control, the British were obliged to establish systems of oppression on a global scale, ranging from the sophisticated to the brutal. These in turn were to create new outbreaks of revolt.

Over two centuries, this resistance took many forms and had many leaders. Sometimes kings and nobles led the revolts, sometimes priests or slaves. Some have famous names and biographies, others have disappeared almost without trace. Many died violent deaths. Few of them have even a walk-on part in traditional accounts of empire. Many of these forgotten peoples deserve to be resurrected and given the attention they deserve.

The rebellions and resistance of the subject peoples of empire were so extensive that we may eventually come to consider that Britain's imperial experience bears comparison with the exploits of Genghis Khan or Attila the Hun rather than with those of Alexander the Great. The rulers of the empire may one day be perceived to rank with the dictators of the 20th century as the authors of crimes against humanity.

The drive towards the annihilation of dissidents and peoples in 20th-century Europe certainly had precedents in the 19th-century imperial operations in the colonial world, where the elimination of "inferior" peoples was seen by some to be historically inevitable, and where the experience helped in the construction of the racist ideologies that arose subsequently in Europe. Later technologies merely enlarged the scale of what had gone before. As Cameron remarked this month, Britannia did not rule the waves with armbands on.

Richard Gott's new book, Britain's Empire: Resistance, Repression and Revolt, is published by Verso (£25).

© 2011 Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. All rights reserved.

[/quote

That map is simply astonishing.

Constance- Posts : 500

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 67

Location : New York City

Re: The British Empire

Re: The British Empire

Sorry for copying the whole review with a onne-line comment. I should have just hit the reply key instead of the quote key.

Constance- Posts : 500

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 67

Location : New York City

Re: The British Empire

Re: The British Empire

blue moon wrote:...it was pretty much a map like that we had when I went to school.

Same here- and that was in the 1960's. Must have been very old text books.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The British Empire

Re: The British Empire

eddie wrote:blue moon wrote:...it was pretty much a map like that we had when I went to school.

Same here- and that was in the 1960's. Must have been very old text books.

Me too

Nah Ville Sky Chick- Miss Whiplash

- Posts : 580

Join date : 2011-04-11

Re: The British Empire

Re: The British Empire

blue moon wrote:...I wonder why pink was the colour of the Commonwealth?

Must be all that fagging at Eton.

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The British Empire

Re: The British Empire

I see that Her Majesty the Queen is presently visiting Oz, and that once again the antipodean chieftans have failed to show due deference. On this occasion, it was a failure to curtsey. Last time, the Oz PM actually dared to touch HMQ. Whatever next?

eddie- The Gap Minder

- Posts : 7840

Join date : 2011-04-11

Age : 68

Location : Desert Island

Re: The British Empire

Re: The British Empire

Sir Thomas Picton? Let him hang

Calls to remove the cruel colonialist's portrait from a Welsh court are wrong – it's a window on a past we need to see, not hide

Jonathan Jones

The Guardian

See you in court … Portrait of Sir Thomas Picton by Martin Archer Shee. Photograph: Dimitris Legakis/Athena

Sir Thomas Picton's portrait hangs in a court room in Wales, sword in hand, as if menacing defendants or reminding them how lucky they are to live in times when the law is less savage than in his day. He was portrayed by Martin Archer Shee in red coat at a bloody battle. Behind him swirl smoke and soldiers. Picton was a British general in the Napoleonic wars and he died of a gunshot wound to the head in 1815 at the battle of Waterloo.

Now the Daily Mail reports that a lawyer who is sick of the sight of Picton wants his portrait to be removed from Carmarthen crown court. It's not that solicitor Kate Williams has anything against Regency-style grand portraiture. No, she objects to Picton's role as governor of Trinidad, where he was accused of brutality in his administration of the colony and its slave-based economy. Even by the standards of the time, Picton's behaviour shocked: he was recalled to England in 1806 to stand trial for ordering the illegal torture of a slave. So Picton was no saint. But, as the local museum argues, his portrait is a historical document from an age with different values. It has hung a long time in the court and to remove it would be to erase a bit of history.

The dispute illuminates the primitive nature of our attitude to portraiture. Deep in our heritage lies the notion that a portrait is a monument to a hero or a worthy ancestor. To portray is to honour. This is why Britain has a National Portrait Gallery, which is essentially a gallery of British heroes.

Among the world's oldest portraits are ancient Roman busts of venerable senators. They are honorific and so is Picton's portrait. By our standards, Roman senators who helped to rule a slave empire are scarcely role models. Nor is Picton. But the demand to remove his portrait is wrong.